7 Sexist Ideas That Once Plagued Science

Ever had a wandering womb?

Science is supposed to be objective — right? By following a careful set of steps, it can tell us how the world works. But looking back on history, that's not at all true, experts say. In reality, science was used again and again to reaffirm whatever prejudices were in vogue at the time — including the idea that women are weaker, crazier, less smart and generally less capable than men.

Here are seven hysterical ideas about women that were once scientific dogma.

Those pesky wombs cause all sorts of problems

Feeling a little off? If you have a womb, you might want to make sure it hasn't wandered out of place, according to ancient Greek and Egyptian doctors. Hysteria, a condition described in the oldest medical document ever recovered, was attributed only to women. Its symptoms were mainly psychiatric and ranged from depression to a "sense of suffocation and imminent death," according to an article published in 2012 in the journal Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health.

Hysteria happened, scientists from the second century B.C. believed, when a womb just would not stay put. (The word "hysteria" even comes from the Greek word for womb, "hustera") Depending on whom you consulted, cures ranged from sexual abstinence to prescribed sex. Or perhaps, some argued, an herbal mixture would be sufficient to fix the problem.

By the 19th century, physicians no longer believed that the womb wandered. But many of the ideas underlying the concept of hysteria — for instance, that female reproductive organs could be blamed for psychiatric problems — stuck around. In fact, as late as 1900, many asylums still performed routine gynecological examinations on their patients , according to a 2006 article written by University of Manchester historian Julie-Marie Strange and published in the journal Women's History Review.

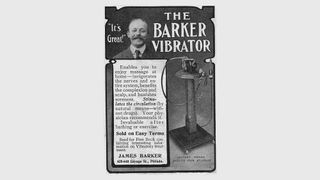

A vibrator could solve all our problems

By the early 20th century, when Sigmund Freud was revolutionizing the field of psychiatry, men and women both received treatment for hysteria. Even then, some doctors still attributed the condition to sexual or reproductive dysfunction in women. Some doctors would use streams of water to induce "hysterical paroxysm" (otherwise known as an orgasm) in women. In the 1880s, Dr. Joseph Mortimer Granville invented a medical tool especially for inducing these paroxysms and curing hysteria, Vogue reported. That tool eventually evolved into the vibrator.

Doctors should be careful not to excite women's passions "too much"

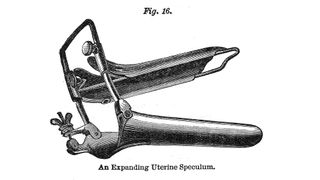

While some doctors prescribed sex to cure women of mental illness, other physicians worried that routine medical checkups might be a little too titillating. In an 1881 issue of the prestigious medical journal The Lancet, doctors said that gynecological exams could "ignite sexual passions in women" and encourage women to "satisfy their own lusts." One husband at the time even complained that the speculum had caused the downfall of his marriage, Strange wrote in Women’s History Review.

Speaking of your womb, did you know it could fall out if you run too much?

In 1967, Kathrine Switzer became the first woman to officially sign up for the Boston Marathon — but race officials didn't know she was a woman. When she told her male training partners she was planning to run the race, they protested, Switzer wrote in her memoir. They thought it was too much for a fragile woman's body, fearing that her uterus might even fall out.

This myth might come from a journal article published in 1898 in the German Journal of Physical Education, according to a 1990 study in the Journal of Sports History. In that 1898 study, a Berlin doctor wrote that exertion could cause the uterus to shift position in the body, resulting in sterility, "thus defeating a woman's true purpose in life."

Today, with more women entering endurance sports, the idea that too much jiggling will cause your uterus to fall out has also fallen out of favor. But the notion still occasionally crops up. In 2005, Gian-Franco Kasper, the president of the International Ski Federation, said on NPR that ski jumping is "not appropriate for ladies from a medical point of view." In 2010, he elaborated on his point by arguing that a woman's uterus could burst when she landed, Outside magazine reported.

Women are basically small men

Until very recently, doctors and scientists considered women, medically speaking, basically the same as men.

"For a very long time, researchers in many fields believed there was a single body and that it was not gendered at all," Naomi Rogers, a historian at Yale School of Medicine, told Live Science.

That is, men were considered the default setting and women were variations on that mold. In fact, it was only in 2000 that the medical community formally acknowledged that "women are not small men," Vera Regitz-Zagrosek wrote in the book "Sex and Gender Aspects in Clinical Medicine" (Springer 2012). This assumption has had profound implications for female patients.

For example, until 2000, women were not always included in clinical trials — meaning that many drugs had been tested only on men, with no sense of how the medications might interact with a woman's body.

But weirdly, our brains are totally different

One of science's more persistent ideas about women is that they're fundamentally different from men in behavior and intelligence due to differences in their brains. That idea began with the field of phrenology, the study of head size that reached peak popularity in the 19th century. For years, scientists argued that women's smaller heads were a sign of their inferior intelligence.

Later, scientists realized that women actually had larger heads in proportion to their bodies. So, researchers proceeded to argue that because women's proportions are more similar to those of children (who also have proportionally larger heads), women must be intellectually similar to children, wrote Margaret Wertheim in the book "Pythagoras's Trousers: God, Physics and the Gender War" (W. W. Norton & Company, 1997).

"You can see the incredible appeal of brain size” as a measure of intelligence, Rogers said. But, she added, phrenology has long been debunked as pseudoscience.

Unfortunately, the idea that differences in female and male brains account for fundamental differences in personality and behavior still arises, Susan Castagnetto, a philosopher at Scripps College in California, told Live Science. For example, differences in the proportion of gray matter and white matter have been used to argue that men are more "systematizing" and that women are more "empathizing."

But, Castagnetto pointed out, there's one major problem with this field of research: We don’t know what this difference actually does. "How do you conclude anything about actual performance based on finding [anatomical] sex differences in the brain?" she said.

There may be differences between male and female brains, but we can't conclude what those differences mean, Castagnetto said.

Periods make women even less fit

Another age-old idea is that people who menstruate are less capable of performing tasks — like leading, attending school or even being good mothers. Beginning in the Victorian era, doctors referred to menstruation as an illness or a disability, Strange wrote. In an article titled "Sex in Education: or a fair chance for the girls," American Doctor Edward Clark wrote that because women menstruate, they have less blood overall compared to men, and therefore less energy. He extrapolated that because of their limited blood supply, school would downright dangerous for girls. After all, he argued, studying could divert a girl's limited blood supply away from vital organs (like her uterus and ovaries).

Though the idea of "limited blood supply" seems comical today, the notion that people who menstruate become indisposed once a month has stuck around. In 1975, Psychology Today ran an article titled "A person who menstruates is unfit to be a mother," Carol Tavris wrote in her book "The Mismeasure of Woman" (Touchstone, 1992). Today, a host of undesirable symptoms — from confusion to asthma to lowered school performance — are all chalked up to menstruation under the name premenstrual syndrome (PMS), Tavris wrote.

"Mercy!" she wrote. "With so many symptoms, accounting for most of the possible range of human experience, who wouldn't have PMS?"

Editor's Note: This story was updated to correct Susan Castagnetto's area of expertise. She is a philosopher, not an ethicist.

Sign up for the Live Science daily newsletter now

Get the world’s most fascinating discoveries delivered straight to your inbox.

Isobel Whitcomb is a contributing writer for Live Science who covers the environment, animals and health. Her work has appeared in the New York Times, Fatherly, Atlas Obscura, Hakai Magazine and Scholastic's Science World Magazine. Isobel's roots are in science. She studied biology at Scripps College in Claremont, California, while working in two different labs and completing a fellowship at Crater Lake National Park. She completed her master's degree in journalism at NYU's Science, Health, and Environmental Reporting Program. She currently lives in Portland, Oregon.