At Wednesday night’s Democratic presidential debate, Sen. Amy Klobuchar was pressed to defend a comment she’d made about Mayor Pete Buttigieg and sexism. If she or the other female candidates had as little political experience as the college-town mayor, Klobuchar had said earlier in the week, they would not have made it onto the debate stage, because women are “held to a different standard.”

She reiterated her point when asked about it on Wednesday. “I think any working woman out there, any woman that’s at home knows exactly what I mean,” Klobuchar said. “We have to work harder, and that’s a fact.” If women and men in politics were evaluated by the same criteria, she continued, “we could play a game called ‘name your favorite woman president’—which we can’t do, because it has all been men.”

Then, Klobuchar addressed a question that hadn’t been asked: whether American voters are ready to elect a female president. She seemed to equate gender with physical attributes—“I don’t think you have to be the tallest person on this stage to be president. I don’t think you have to be the skinniest person.”—and tried to dispel voters’ fears that a female Democratic nominee would be unable to defeat Donald Trump. “I think what matters is if you’re smart, if you’re competent, and if you get things done,” Klobuchar said. “If you think a woman can’t beat Donald Trump, Nancy Pelosi does it every single day.”

It’s a tough line to walk—acknowledging that sexism infects systems of power, including politics, without scaring voters into thinking the sexism is single-minded and blunt-force enough to preclude every woman’s eventual success. Klobuchar did a good job of it. But the question of whether America is too sexist, or the female candidates too personally unappealing, to win the presidency will continue to loom over campaign coverage. Since the very beginning of the race, pollsters and reporters have been trying to gauge the volume and consistency of voters’ negative reactions to the women running for president.

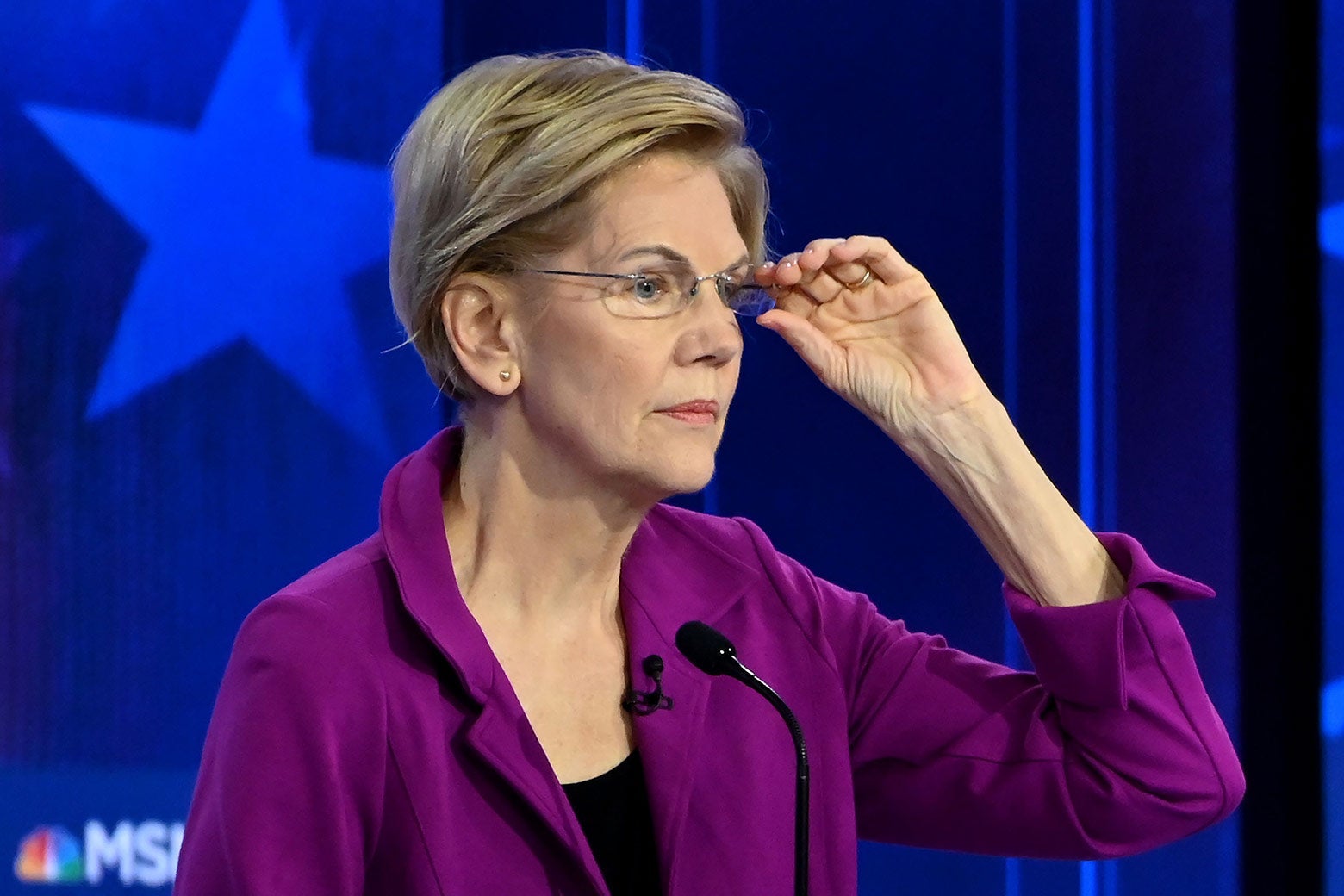

Much of this attention has focused on the only female front-runner, Sen. Elizabeth Warren, and her capacity to be liked. The question of Warren’s likability was put to the American public before her presidential candidacy had even begun. On the last day of 2018, a few hours after she announced that she’d formed an exploratory committee, Politico published a piece that claimed some “Washington Democrats” consider Warren too much like Hillary Clinton—“too unlikable,” too “cold” and “aloof”—to beat Trump.

Warren attempted to use the piece, and the bevy of critical responses that followed, to gin up outraged donations from her fans. “We’re used to the tired, beard-stroking opinion pieces masquerading as smart political analysis,” read a fundraising email Warren’s team sent out a couple of days later. “We’re used to being compared to any woman who’s ever lost an election.” The email suggested supporters send money to the Warren campaign whenever they read “gendered nonsense commentary” about her candidacy, “like a swear jar.”

It’s been nearly a year since that email, and if voters have actually been contributing to the likability swear jar, it must be almost full. The idea that Warren isn’t likable enough to win the general election made headlines in early November, when a whole bunch of swing-state voters told New York Times pollsters that most female candidates for president “just aren’t that likable.” Of 205 respondents who said they’d vote for former Vice President Joe Biden but not Warren, 41 percent agreed with that statement. That 41 percent is “disproportionately male and working class,” according to the Times, and a real treat of a voting bloc: A majority said “discrimination against whites” has gotten just as bad as discrimination against people of color, and 79 percent believe “political correctness has gone too far.”

In a political climate that still takes seriously the concept of likability as an important and measurable marker of electoral viability, it was almost a relief to see voters expose it for what it is: a socially acceptable container for socially unacceptable bias. So much sexism in politics comes as a dog whistle: Biden, who ended Wednesday’s debate by yelling at “woe is me” voters to “get up” and do something, calls Warren, the candidate who calmly replied “thank you” after he yelled at her during October’s debate, untenably “angry”; Pete Buttigieg, whose campaign appears to be suggesting that he fails to excite black voters because black people are singularly homophobic, characterizes Warren’s approach as “divisive” and too focused on “fighting.” Female candidates can make themselves crazy wondering whether they’re being unfairly smeared with gendered critiques or just overreacting to run-of-the-mill attacks on a front-runner. But when voters are willing to agree with a generalized negative statement about an entire gender of politician, the answer becomes clear.

Likability is an undefinable, unmeetable demand voters make of female candidates but not their male counterparts. That makes it a useful indicator of sexism among people who won’t say they’re sexist. The nonpartisan Barbara Lee Family Foundation, which does research on women in politics, found that voters “have an ‘I know it when I see it’ mindset” when it comes to likability: They are unable to articulate what it is that makes them “like” a candidate, but they say they are less likely to vote for a woman who doesn’t have it, even as they’ll gladly vote for a man they don’t like. In the BLFF study, the images of female candidates voters rated least likable were photos of women seated alone at mahogany desks—the position those women would assume in their offices as political leaders. I think I can help those voters articulate what they didn’t like about that!

Voters intuitively know that likability, insofar as it matters as a quality in a political leader, is a sham, even if they’re not self-aware enough to recognize it. Consider the current president, who shows open contempt for his own supporters and has barely demonstrated the physical capacity to chuckle. When I talked to a bunch of senior citizens from across the political spectrum in September, even the people who said they supported Trump were quick to note that they didn’t like him as a person. (If voters like Trump, they like him because he terrorizes people less powerful than him, and being mean can sometimes feel nice—not because he’s particularly likable.) Sen. Bernie Sanders, another Democratic front-runner, is famous for his blunt speaking style and impatience with niceties, but likability rarely enters the public conversation about his ability to defeat Trump in 2020.

That’s partly because likability doesn’t sway elections. “The American people are not going to decide who they are going to have a beer with, because the American people know that they are not going to have a beer with any of these people,” political science professor and likability researcher Mo Fiorina told NPR back in 2012. “They are going to decide on the base of who they know is going to do the job.” Likability, like relatability, is also shaped by the worldview of each individual voter, making it a particularly subjective attribute. George W. Bush, who was widely hailed as an impeccably beer-ready politician—despite his renouncing alcohol after years of drunken misbehavior—did not come across as a likable candidate to voters who were disinclined to warm to homophobes or otherwise put off by upper-crust entitlement.

Granted, sexism is a more widely held social bias than any aversion to Bible-thumping frat boys. But there’s no strong indication that a lack of likability is what will keep Warren from beating Trump if she wins the nomination. For one thing, voters hate everybody: Every candidate for president, including Trump, was rated more unfavorable than favorable in Monmouth University’s most recent poll. And many of the Biden-not-Warren voters in the New York Times poll seemed to have serious political objections to Warren’s candidacy that complemented their sexist objections: 74 percent said they’d prefer a moderate Democratic nominee, and 41 percent—the same proportion that said they didn’t find female candidates likable—described themselves as “conservative.”

In recent years, research on sexism among voters has helped female candidates develop blueprints for their campaigns. When I interviewed political speech coach Chris Jahnke in August, for instance, she told me voters find female candidates more likable when they share credit for their accomplishments (e.g., “I led the team that passed X bill”), so female candidates will often try to write their speeches this way. (As I watched Biden try to take credit for Warren’s creation of the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau at the October debate, I thought: Really? Just the voters?) It makes sense that candidates would try to mitigate any gender-based obstacles to being heard.

In Warren’s debate performance on Wednesday, she was just as fervent as ever in her exhortations against corruption and income inequality; she doesn’t appear to be letting the criticism from random anti-PC voters and her fellow candidates get to her. But even when female candidates try to bend their personalities to fit the double binds they’re caught in—strong but not shrewish, change-oriented but not angry, accomplished but not uppity, passionate but not “hectoring”—those parameters keep shifting, because the parameters are fake. There’s no objective threshold of volume or tone a woman’s voice must meet before she’s called angry. There’s nothing a woman can wear, nowhere she can place her hands when she speaks, that will prevent people from comparing her to a schoolmarm. Politicians and pundits rebuked Clinton for failing to smile enough during a presidential debate. When Clinton did smile and laugh, her detractors used images of her smiles and laughs to paint her as a deranged madwoman.

Warren has become known for taking thousands of one-on-one photos with people who want to meet her after her campaign events. It’s hard to imagine a tradition less in line with the solo-mahogany-desk-sitting vision of leadership, and yet voters are still willing to lump Warren and all the other female candidates together as people who “aren’t that likable.” People who criticize a female candidate with mushy, demeanor-based slights aren’t commenting on her actual behavior. They’re objecting to her performance of womanhood in a venue—political leadership—where a woman’s presence just feels kind of off.

Since voters aren’t working from any single accepted definition of likability—or coldness, or aloofness, or anger—it seems foolish to try to accommodate them. There is no accommodating them, because their judgments aren’t based on rational metrics. Sexist voters turned off by presidential candidates who just so happen to be women aren’t going to be won over by a pleasant lady who smiles and makes bland pronouncements of unity when faced with a climate apocalypse and a rapacious health care system. (Too weak! No spine!) The only thing that will inoculate the public to the jarring novelty of women in positions of power is more women in positions of power. The waning of sexism in politics won’t be marked by people starting to like women in leadership but by the decline of likability as a political criterion—by people not liking female candidates, the same way they don’t like male candidates, and voting for them anyway.