In 1939, the artist Augusta Savage was the first African American woman to open her own art gallery in America – the Salon of Contemporary Negro Art. Devoted to showcasing the work of black artists, 500 people poured into the opening reception, where Savage announced: “We do not ask any special favors as artists because of our race. We only want to present to you our works and ask you to judge them on their merits.”

Eighty years later, her work is currently on view at the New York Historical Society until 28 July. Augusta Savage: Renaissance Woman highlights over 50 sculptures, photos and letters that detail Savage’s influence as an overlooked artist, activist and educator, a trailblazer of African American arts from the Great Depression to the postwar period.

“It’s the first exhibition to look at her career, but also how she struggled through poverty and racism,” says the curator, Wendy NE Ikemoto. “She often didn’t have the funds to cast her sculpture in bronze, or the money to store them. Many were cast in plaster and painted with shoe polish to make it look like bronze.”

Savage, who was born in Florida in 1892, moved to New York on a scholarship to study art at the Cooper Union. In 1923, she won a scholarship to study at the Fontainebleau School of Fine Arts in France, but the French government retracted her admission after learning she was black.

A typewritten letter from the admissions committee reads that “it would not be wise to have a colored student … as complications would arise, and the student would suffer most from these complications”.

“She alerted the press, [and] it made headlines,” said Ikemoto. “As a black woman during the Jim Crow era in the 1920s, it was really extraordinary.”

Her friends and colleagues in the Harlem community helped her, such as WEB Du Bois, who wrote letters on her behalf to fight for her admission. In 1929, she was permitted to study in France and upon her return, she founded her own art studio and school. In 1932, she founded the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts, which became a training ground for African American artists who would later show at her gallery.

“She set her focus on race-based art and activism that would last for the rest of her life,” said Ikemoto.

Her studio was the foundation for some of the most well-known figures of the Harlem Renaissance. Savage taught artists such as abstract painter Norman Lewis, figurative painter Jacob Lawrence and portrait artist Gwendolyn Knight.

But this exhibition puts the works of Savage on view alongside her students. Some of her rare sculptures are included, such as Gamin, a 1930 portrait of her nephew Ellis Ford, and Diving Boy from 1939, two of 12 sculptures of her work that still exist today.

One of her most poignant pieces is a bust of the boxer Jack Johnson, in a work dated from 1942 entitled the Pugilist. It shows Johnson, who became the world’s first black heavyweight champion after beating the Canadian Tommy Burns in 1908, standing with his arms crossed.

“It’s a tiny sculpture but has enormous presence. It captures her own fighting spirit in fighting alongside him against racial oppression,” said Ikemoto.

Her most famous artwork is the Harp, which shows a choir of black children singing. It’s based on “Lift every voice and sing”, the first line of what was referred to as the “Negro national anthem” – a poem initially written by James Weldon Johnson in 1900. The Harp had a central location at the 1939 World’s Fair, resulting in its own postcard.

At the time, Savage was the only black woman to be commissioned at the fair – she was paid $360. But the sculpture was destroyed by bulldozers as part of the fair’s cleanup, and all that remains is a replica of a souvenir that existed at the time. “It was apparently one of the most popular works in the fair, seen by over 5 million people,” said Ikemoto. “It’s an extraordinary loss.”

With her own struggle to get an education, Savage devoted her life to teaching other black artists how to sculpt, draw and paint. “She said her legacy is in the work of her students,” notes Ikemoto. “Even when they didn’t have money to buy their own art supplies, she let them use hers. She often said, ‘I know much I was put down and denied, so if I can teach these kids anything, I’m going to teach it to them.’”

Her legacy lived on in one the sculptor Charles Alston, one of Savage’s students famed for his bust of Martin Luther King Jr, which was the first artwork of an African American in the White House. He also established the Harlem Artists Guild, which helped create career opportunities for black artists, and continued Savage’s legacy for civil rights activism through art.

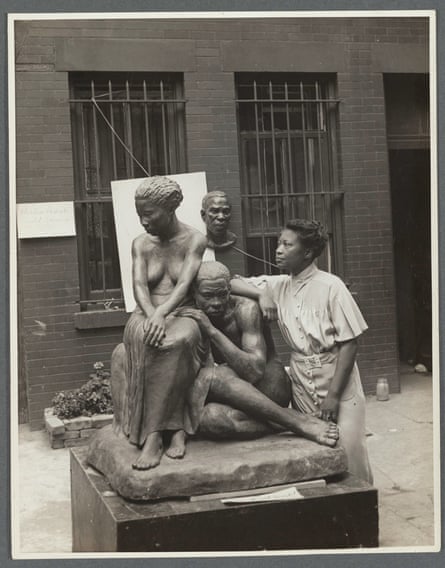

There are stunning photos of Savage in the exhibition, from studio portraits to group shots with other Harlem artists, and one of her alongside her sculpture Realization from 1939, which shows a black couple crouched in oppression. “What I think is being realized in this piece is slavery. It’s about the psychological trauma of the moment after this couple has been sold, stripped to go on the auction block,” said Ikemoto.

“Savage strived towards a different type of monument. So many slavery monuments are about abolition and emancipation – this is a different way to remember slavery.”

Unfortunately, like so much of Savage’s artwork, it no longer exists today. “That’s one of the struggles of this exhibition. It’s a lot of recovery work,” she said.

Some were destroyed by the artist, and others fell apart, having been made with fragile materials like plaster. Others mysteriously disappeared and haven’t been found.

“She’s been lost to history, compared to her well-known students, who had increased attention,” said Ikemoto. “She was before that time.”

“It was a way to combat stereotypes in visual culture in the age of Jim Crow,” said Ikemoto. “She’s a great reminder of the crucial role of having a multiplicity of voices in the public space.”

This exhibition, initially curated by Jeffreen Hayes, travels from the Cummer Museum of Art and Gardens in Jacksonville. It’s the first large-scale exhibition of Savage’s work since the 1980s.

Despite the fact her own self-initiated art gallery only lasted a few months before it ran out of funding, the handful of photos show the artist in her prime – dressed for success and surrounded by the works of black artists, many of whom were her students.

“She was keen on creating an infrastructure for black artists, the need for a network for African American artists to succeed,” said Ikemoto. “Savage once said in all the African American homes she visited, only two had artworks by African American artists. She asked: ‘How does the African American artist survive?’

“She put a lot of thought and energy into creating these intellectual spaces and networks for the work of black artists.”