Many Nobel prizewinners believe that bias against women explains why so few female researchers have won science’s top award, a Times Higher Education survey has revealed.

As part of a poll of science’s leading figures, the initial results of which were published last month, about 50 Nobel prizewinners in science, medicine and economics were asked why the list of Nobel laureates remains so overwhelmingly dominated by men.

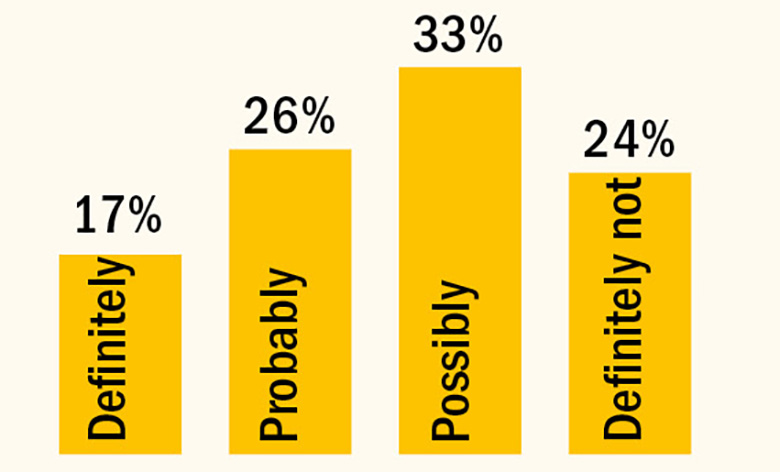

In results released ahead of the announcement of the Nobel prize awards in Stockholm next week, 17 per cent of respondents felt that the lack of female laureates definitely reflected bias, while a further 26 per cent felt that it probably did. Another 33 per cent agreed that it was a possibility, although 24 per cent ruled out the idea.

Only 6 per cent of winners in medicine since 1901 have been women, while the proportion falls to 2.3 per cent in chemistry, 1.3 per cent in economics and 1 per cent in physics, according to an analysis conducted in 2015, the year in which chemist Youyou Tu was the last female winner.

Does the fact that so few women have ever won a Nobel Prize reflect bias?

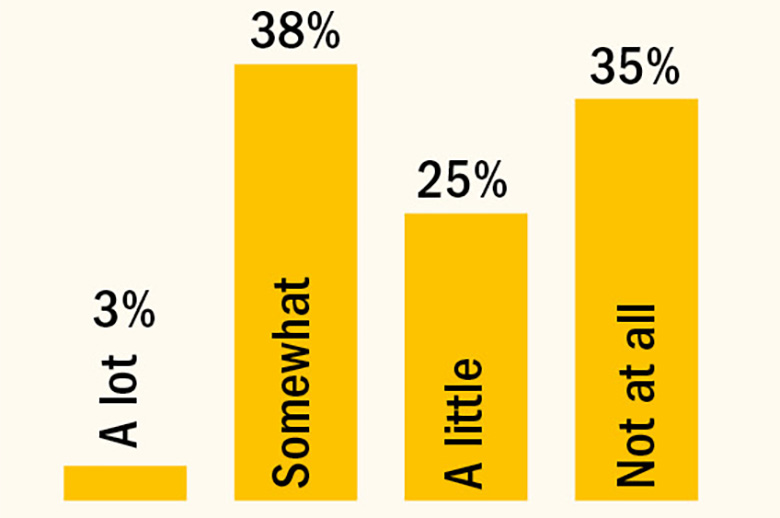

Does the lack of female Nobel winners devalue your own awards?

Responding to THE’s poll – which captured the views of about one in five living laureates – Richard J. Roberts, the English biochemist who won the 1993 Nobel Prize in Medicine, said he was concerned that female scientists received “short shrift” regarding the perception of their contribution towards a discovery.

“Rosalind Franklin and many more women have had to take a back seat when the Nobel prizes are awarded,” said Sir Richard, who believed that women are often pushed off the Nobel shortlist (limited to a maximum of three people) when judges decide who should get credit for a specific body of research.

“There are many, many candidates for each Nobel prize, with many more scientists and interested staff [now] laying claim to a single contribution highlighted by the Nobel prize,” explained Sir Richard. “I shared my Nobel prize with one other person but there could have been a couple more people on the ticket."

Peter Agre, who won the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2003, said that the long list of overlooked women highlighted the “prejudice” and “short-sightedness” of previous Nobel panels.

Professor Agre, director of the Johns Hopkins Malaria Research Institute, listed physicists Lise Meitner, sometimes known as the “German Marie Curie”, and Deborah S. Jin as women who should have won.

However, science is now “past this sort of blindness”, said Professor Agre. It now needed to address “the more fundamental problem of the participation and recognition of women and minorities in all of the sciences”, he said.

“Five women shared the Nobel prize[s] in 2009, so I think the story will soon be very different,” said Professor Agre. Just 17 women have ever won a Nobel prize in science or medicine, with most of the 48 female winners recognised in the peace and literature categories.

One US laureate, who wished to remain anonymous, called the lack of female winners an “embarrassment to all of science”, but many pointed out that the fault lay in science more generally rather than the Swedish Academy of Sciences, which awards the prize.

One US researcher blamed the “systematic devaluation of women’s role in science”, while another US winner said that the problem is “clearly societal and one cannot blame scientists nor scientific institutions for the way in which our Western societies are organised”. Another US-based winner cited the issue of “bias at all levels of science [that] directly or indirectly affects the Nobel prize decision”, while one Israel-based winner bemoaned a “system that produces less brilliant women scientists”.

Asked whether this lack of female winners devalued their own Nobel awards, 38 per cent of laureates in THE’s poll, which was assisted by the Lindau Nobel Laureate Meetings organisation, replied “somewhat”, 25 per cent said “a little” and 3 per cent said “a lot”, although 35 per cent said “not at all”.

Brian Schmidt, the astrophysicist who won the 2011 award in physics, said that unless more women won in the near future, “it will devalue them a lot”.

“To some extent, Nobel prizes reflect the lack of diversity in the past, but the [percentage] of female winners has not improved as much as I would expect given the pool of exceptional discoveries being made by women over the past 25 years,” said Professor Schmidt, who is now vice-chancellor of the Australian National University.

“I would be deeply disappointed if the number of female recipients does not rapidly rise over the coming decade,” he added.

POSTSCRIPT:

Print headline: Do Nobels snub female scientists?

Register to continue

Why register?

- Registration is free and only takes a moment

- Once registered, you can read 3 articles a month

- Sign up for our newsletter

Subscribe

Or subscribe for unlimited access to:

- Unlimited access to news, views, insights & reviews

- Digital editions

- Digital access to THE’s university and college rankings analysis

Already registered or a current subscriber? Login