In 1876, the Waltham Watch Company sent 18 workers to work in its demonstration assembly line at the Centennial Exhibition in Philadelphia. Thirteen of them were women.

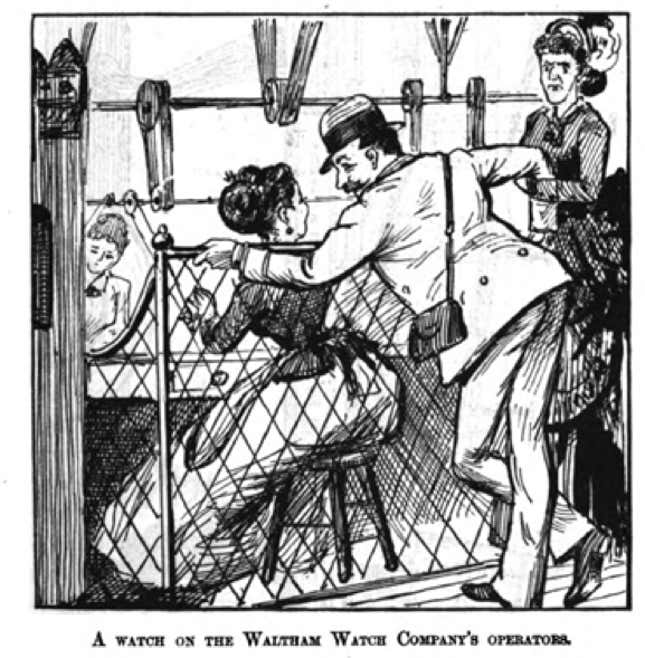

At the time, society was still adjusting to the idea of women working at all. Visitors to the Centennial—which drew 10 million global visitors—were not sure what to make of the women workers. A publication called Bricktop Stories wrote that Waltham “has its machinery and its pretty girls at work, making every part of a watch, and keeping jealous wives on the watch, as their husbands suddenly become interested in the wonderful mechanical manipulation of that delicate machinery and those deft fingers. This alone is worth going a hundred miles to see.”

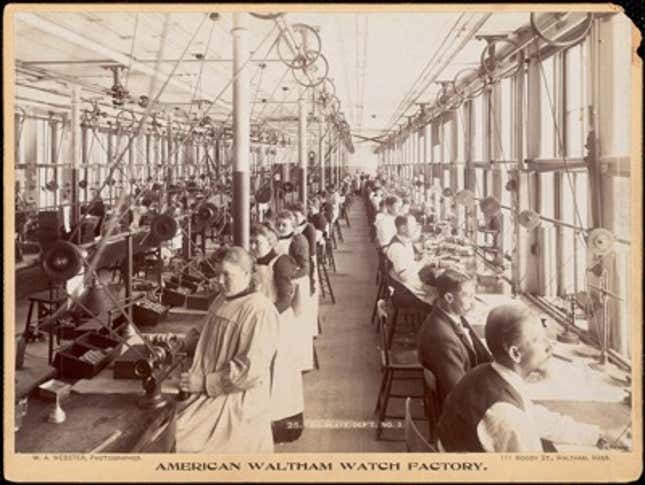

But Waltham had gone further than hiring a workforce of 1,000 that was 40% women. At a time when even the sight of a woman at work was something people gawked at, the watchmaker also had a documented policy of equal work for equal pay. Judges from the Centennial Exhibition, factory observers, and a reporter each wrote about this progressive policy and the strict adherence in three publications between 1876 and 1887. One even claimed it was “rigidly observed.”

Waltham, like many progressive companies today, still failed to live up to its policy.

Waltham’s 19th-century records are maintained in the Special Collections of Harvard Business School’s Baker Library, where the wage logs still record exactly what each employee was paid each month. Using a sample from 1876, the wage records show non-manager men earning $2.43, while women earned an average of $1.22. How did this company, which made seemingly every effort to pay women and men equally, end up paying women exactly half the wages?

Its reasons for failure remain relevant stumbling blocks today:

1) While the company had a policy of equal pay, it did not employ women in all jobs equally. The company had a bias as to what work it thought women should do or where they were best suited. An 1887 observer wrote: “The work to which the softer sex are assigned is always of a lighter character and much of it is very dainty and delicate, requiring keen eyes and deft fingers, but neither trying to the mind nor injurious to the body.” What Waltham projected as women’s work presented an immediate structural barrier for upward mobility for women within the company.

2) When the reporter visiting the Waltham factory in 1887 lauded the company for its policies, even he noted that women were not actually paid the same once factoring in that women were not employed across all positions equally. Despite 11 years passing since the Centennial, and Waltham having an equal pay policy the entire time, this reporter found that women still earned about 50% of men. The writer noted that women and men earned the same pay in many simple jobs, but the average pay of both genders in the factory was not equal, something for which he quickly provided a seemingly logical explanation. He said the chief reason was that women did not work long enough in the factory to gain the same skills as men. One of the reasons was that women would often leave work when they married and subsequently started a family. About 20% of the Waltham women were married and continued working. However, the majority left after marrying, making the average woman worker 20 years old, and the average male worker about 30 years old.

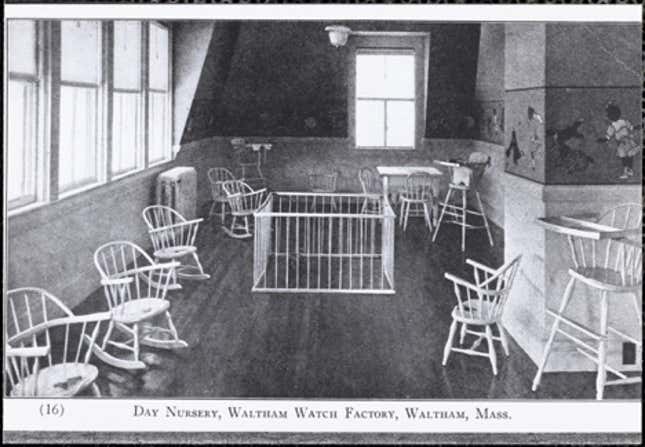

The company tried to minimize the obstacles for working mothers. Despite a history of progressive policies towards women in the workplace, none of these were not enough to overcome new mothers being away from the factory for maternal leave. During this period, the technology of the company was quickly advancing, leaving new mothers with a skill deficit on the new machines. When women could return to work, they had to re-acquaint themselves with the machines while their male counterparts continued to progress during the entire process. As a symbol of its value of its women workers, Waltham was even an early adopter of on-site childcare by the very early 20th century.

3) In its earliest years, Waltham was noted as never asking women (or letting them) work overtime, while men worked overtime as needed. With overtime came more hours worked and cumulatively higher pay and experience. Women were not employed with overtime because of the societal perception of when and how much women should work.

Though society has progressed over the last century, there are still jobs that people unconsciously view as a woman’s job or jobs that are best suited for men. Having children is still bad news for women’s pay. And the perception about when and how much women should work that once kept Waltham’s women workers off of overtime can be seen today in unequal offerings or applications of parental leave. A Harvard Business Review article reported that college-educated women continue to work significantly fewer hours than the same population of men. This is a fact that much of society accepts as perfectly normal and a cost of women’s choices, rather than questioning the underlying role-biases within the workplace.

While Waltham had a progressive view for its era and was one of the first companies to think deeply about the gender wage gap issue, it still failed in its quest to pay women and men equally. Trying with simple policies was not enough to overcome inherent structural biases built into the company’s way of doing business. That is because it is not simply company policies or even perks such as on-site childcare that can solve the age-old problem. Rather, it requires changing the way a company views and structures its culture. Policies must inform the culture and transform the way a company projects women in the workplace. The lesson of Waltham is that we have been stuck on favorable but simple company policies to “solve” the problem for more than 100 years without ever seriously addressing how we project women in the workplace with those policies.