Nesreen Ghonaim steps off the curb and into traffic. Cars slow, allowing us to cross. It’s a few minutes past 7pm and the running group she leads is waiting. She hustles down the walkway, a wide meridian stretching the center of Tahlia, one of the busiest shopping streets in the port city of Jeddah. Her black abaya, the long robe women must wear in public, swishes around her calves.

Nesreen is 43, with warm eyes, high Egyptian cheekbones, and curls that bounce as she moves through the evening crowd. Twenty feet ahead, about 15 women wait in the walkway. They all wear abayas, running shoes, and various forms of head covering, from the veiled niqab to a loose hijab, or no head covering at all. The women—mothers, professionals, students—smile and embrace us when we arrive. This is JRC Women, a division of the local running group Jeddah Running Collective, which Nesreen heads. They’ve recently launched a couch-to-5K program to welcome newcomers, and while some in tonight’s group have been members for a couple years, many are new.

“All right, gather round,” says Raghad Almarzouki, 31, who tag-team coaches JRC Women with Arwa Alamoudi, also 31. “We’ll run down the walkway, out to the grassy area and back,” she says, detailing the 5K route. She waves her hand, “Yalla.” Let’s go.

The women take off down the path, a mosque across the street on one side, a female-only Gold’s Gym franchise on the other. Couples stroll as children dash about. A man kneels on a prayer rug. Veiled women walk with cell phones to their ears, and SUVs, luxury sedans, and the occasional rundown Toyota whiz by.

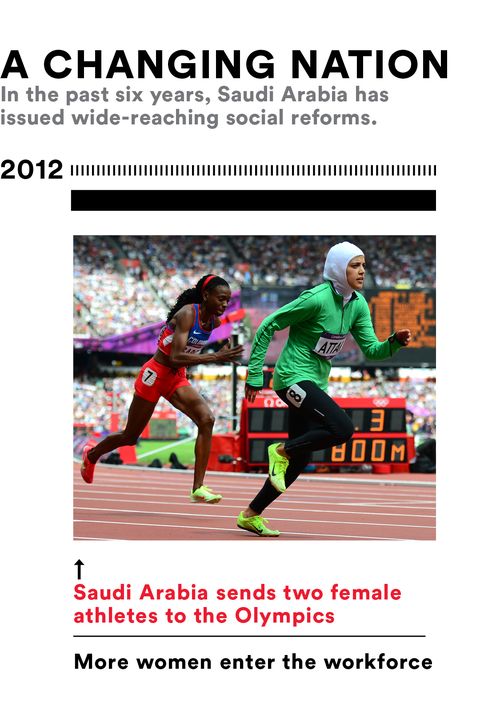

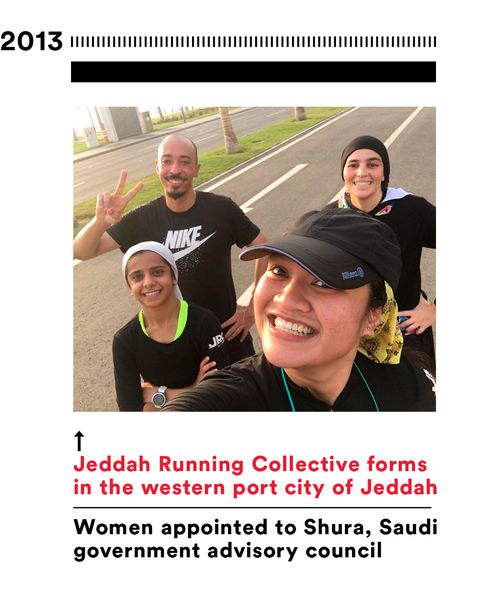

The moment seems ordinary: a group of women out for a run in a city. Except that it’s revolutionary. The Saudi Arabian government, a monarchy that follows a conservative form of Shariah law, effectively banned women’s sports for decades. In the 1960s, when the country launched widespread public schooling, it prohibited physical education and sports for girls and barred women from forming sports teams or participating in sporting events. When JRC was founded in late 2013, the country had no women’s running groups.

Now, from the western city of Jeddah, to the capital, Riyadh, to eastern Khobar, women are running in the streets, claiming a place and activity long considered inappropriate for their gender. In each city the running scene is a unique blend of the women themselves, the run groups, and the local political climate. The common thread: The women, and the men supporting them, are committed to advancing Saudi culture around women’s sports.

“Saudi society has traditionally viewed women exercising in public as taboo or improper,” says Mezna AlMarzooqi, Ph.D., a public health professor at King Saud University in Riyadh who researches activity levels among young, educated Saudi women. As recently as 2016, women who wanted to slip out for a five-miler worried they would be stared at, harassed, or even stopped by the Mutawwa, Saudi’s religious police who enforce the strict mores on modest dress and behavior, including mixing with the opposite gender. Historically, the Saudi government believed that interactions between men and women who are not related could lead to immoral behavior. Because of that, Saudi became the most gender-segregated country in the world. Restaurants have separate sections for “singles” (men) and “families” (women, children, and their male relatives). Some shopping malls have designated female-only floors. Almost all schools are single-sex, as are universities. And until recently, the government did not issue licenses for women’s gyms.

So women ran on treadmills at home. They held yoga, Pilates, kickboxing, and other fitness classes at their houses. They also engineered creative workarounds to the licensing issue by fronting a gym with a seamstress shop, or opening a fitness studio in a hospital or hotel, where a license wasn’t required. Some women joined the running groups and fitness classes that take place inside walled compounds—gated communities where foreign workers live more Western lifestyles.

Back on the Tahlia walkway, Raghad waits until everyone has caught up, then leads the group down a side street. We run alongside the high walls, ubiquitous in Saudi Arabia for privacy, and eventually come to the wide grassy field where the women move through conditioning drills—lunges, squats, leg swings—sweat glistening on their faces. The run back along the walkway is quieter, the heat, 75 degrees, 70 percent humidity after dark, weighing everyone down. One woman slows to a walk. Her daughter runs ahead. As the run ends, another woman bolts to the curb to take advantage of an ice cream truck. After postrun high-fives, the women gather for the requisite group-run selfie. Munira Abdalwahid, 30, a tall, confident runner who’s been part of JRC for more than two years, raises her phone to the sky, finds the smiling faces, and snaps the shot.

Ask Westerners what they know about Saudi Arabia, and you’ll likely hear two points: oil wealth, and its oppressive laws and practices against women. Yet the JRC Women don’t fit that part—they have a joie de vivre, a badass quality. As Mashael AlShehri, 22, one of the first female JRC members, puts it, “There is no law that says women can’t run. It’s just not common—it goes against our culture.”

I’ve followed JRC for three years, talking and emailing with Mashael and dozens of other women and men, including Nesreen, Raghad, and Arwa. They’ve been patient in explaining the nuances of Saudi life, and the challenges and joys of running, and running with men.

They told me that while genders are segregated, this feels “normal.” And while women’s running and mixed running are not yet common, the goal is to make what seems radical become ordinary.

“We didn’t think it was bold at the time,” says Rod, JRC’s founder. (Rod, who asked that his last name be withheld, was jailed by the Saudi religious police in 2013 and 2014 for running in public with women.) In 2011, Rod began running Jeddah’s walkways and corniche, the promenade along the Red Sea, and noted that no women were out running. Aiming to change that, he and two friends set up a Tumblr and Facebook page and launched JRC as a mixed group in 2013. They quickly realized not all Saudi women were comfortable running with men, so they created JRC Women.

Both groups grew steadily, first with 25 runners, then 50. People did stare at the women. Some men yelled at them to go inside, that they shouldn’t be running. The hashtag #YouAreNotAllowedToDoThat appeared in Arabic on Twitter next to a video of a woman running. Still, each week, Rod and Nesreen responded to inquiry after inquiry, and more women, and men, joined them.

Then, one day in March 2016, a mixed JRC group was stopped by two religious police. The officers asked the men why they were doing “such things,” Rod told me. “We were like, ‘what things?’ We’re stretching to get ready for our usual run.” The police rounded up five male runners and took them in for questioning.

“It was ridiculous,” Nesreen told me. “Stopped for what? For promoting something that is good for human beings.”

None in the group thought about stopping—running had already changed their lives. Nesreen had been a pack-a-day smoker lost in her work, motherhood, and marriage when she learned about JRC. “I found myself through running,” she says. She brings her son, Saif Al-Turki, 19, on her group runs, and it’s brought them closer. Raghad’s sister suffered from depression, and their home felt like a dark place. “Being able to run was freedom,” she says. “It saved me from going into my own depression.” For Arwa, running helped her gain more self-esteem and confidence: “Challenge yourself, see your limits. I understood this from running.”

JRC ran on, finding the line between respecting culture and working to change it. They moved the Tuesday mixed workout to an undeveloped lot. At Saturday morning long runs on the corniche, the men and women started at opposite ends and waved as they passed. Often, they disappeared into the Hejaz Mountains, where women could run without abayas or Mutawwa on patrol.

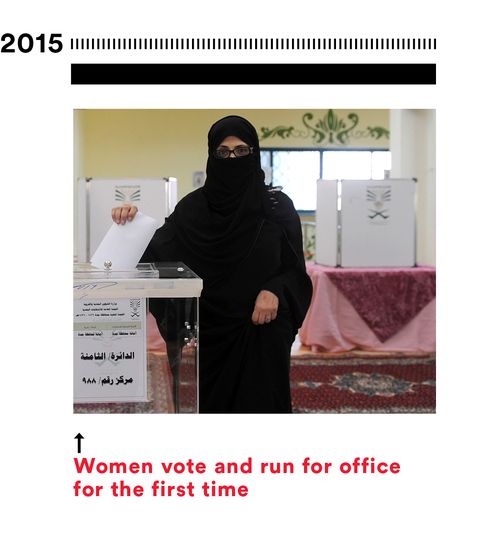

But by then, Saudi Arabia was changing. More women were entering the business sector. Young people were mixing in cafes. The first women had been sworn in to the Shura, the Saudi government’s advisory council. A month after JRC’s incident with the Mutawwa, the government stripped the religious police of their power to arrest. They also announced sweeping economic and social reforms in a plan called Vision 2030, which included a commitment to encourage more sports participation for all. That summer, Saudi Arabia sent four women to the 2016 Olympic Games, and created a new women’s division in its national sports federation.

“We’re part of the change going on right now,” Nesreen says of JRC’s effort to shift cultural attitudes about mixing and women’s running. “It doesn’t come overnight. You have to be patient and persistent.”

Listening to Nesreen and the other women, I thought of the pioneers of women’s running in the U.S. Bobbi Gibb, who ran the Boston Marathon in 1966, when women were barred from entering, and Katherine Switzer, who the following year was nearly pulled off the Boston course by race director Jock Semple. Switzer finished, later saying she knew that if she quit, it would have sent women’s sports back.

What confused me, though, was what I wasn’t hearing. Saudi women still live under a male-guardianship system that requires a man’s permission—father, husband, brother, son—to travel internationally, marry, and in some situations, seek medical attention or work. A guardian can file a legal complaint against a woman for disobedience. His permission is necessary for her to leave jail. The country is ruled by an authoritative, conservative theocracy that has silenced peaceful dissent as recently as May 2018, when multiple women’s rights advocates who had lobbied against the driving ban were jailed despite an announced end to the ban coming in June.

Yet when I asked about barriers, the women cited the oppressive heat. When I asked what made them passionate about the sport, they told me about the satisfaction of finishing a Spartan race in nearby Dubai, which allows women to race, or the beauty of an early morning run in the mountains when the sun was coming up. Most talked about the love they had for running, and the community they’d discovered. But they said nothing about breaking free of restrictive lives or running for liberation. Why? Wasn’t this a revolution? What was I missing?

To better understand the emerging women’s running scene in Saudi Arabia, I flew to the country for three weeks in March, splitting time in Jeddah, Riyadh, and Khobar. Jeddah is the county’s liberal heart, where change begins. Women started wearing colored abayas here before the trend appeared in other cities. It’s where an experiment like JRC slowly expanded into JRC Women, and where the latest running group, Jeddah Runners, now welcomes both men and women. It’s also where the nation’s changing rules are most visible. On the bike path along the Red Sea, women and men can be seen running and cycling, separate but together, all part of the expanding fitness scene for both genders. The government now opens the municipal stadium one night a week for community sports, and men, women, and kids all run, cycle, and play in a place where Saudi women had previously been banned. “You can feel the change all around you,” Nesreen says. “There’s a real community feel around fitness.”

This doesn’t mean the tension is gone. “You will find people who think this is too much,” Nesreen tells me, referring to both women’s running and mixed groups. What’s more, not all Saudi women think running is the right vehicle for advocacy. When I asked the Rasha Alharbi, 45, one of the founders of Bliss Runners, Jeddah’s second and more beginner-friendly club, if she saw her group as part of the push for women’s freedoms, the poised and outspoken mother of four quickly called me out. “Westerners always want it to be about women’s rights,” she said. “Saudi people are talking freely about important issues for women, and it’s time for those discussions. Is that through running? I don’t know. My emphasis is on health.”

There’s good reason for that. Over the last few decades, Western fast-food chains have popped up in Saudi cities, and the increase in processed foods and portion sizes, along with a predominantly sedentary lifestyle—Saudi Arabia was the third most inactive nation in a 2012 Lancet report—has contributed to an obesity crisis. Seventy percent of the adult population is estimated to be overweight or obese, right on track with the U.S. And women are at a higher obesity rate than men (41 percent versus 30). Health and gender researchers attribute the discrepancy, at least in part, to unequal access to sports.

Bliss’s coach, Muna Shaheen, 50, a certified personal trainer, watched people she knew in Jeddah suffer due to high blood pressure and diabetes. “I don’t want to be like them,” she says. “We want to create a different society, a healthy one for ourselves and our children.”

Which is why Bliss created a teen division, Jeddah Teen Bolts, and opened it to girls and boys. “We shouldn’t have to drive our kids to separate gyms or have the boys outside and the girls and women inside a compound,” Rasha says. “We want to be outside together.”

One evening I run with the Bolts, and while they don’t say much about health, they have strong opinions about mixing. Aroub, an articulate 13-year-old girl with braces, says, “We’re going to be mixing in the workplace, so we might as well learn to communicate with the opposite gender now.” A boy drops back and joins Aroub and me. “I thought you might want the male perspective,” he says, grinning. Malik, 16, has thick wavy, hair and a bright smile. “Running with girls gives you more respect for women because we are running the same distance and speed,” he says. Later, Hala, 16, forthright like her peers, tells me it’s important for women to be seen running. “It opens minds about the ‘Ideal Saudi Woman,’ which is seen as covered and not moving,” she says. “That’s not the Saudi woman I am.”

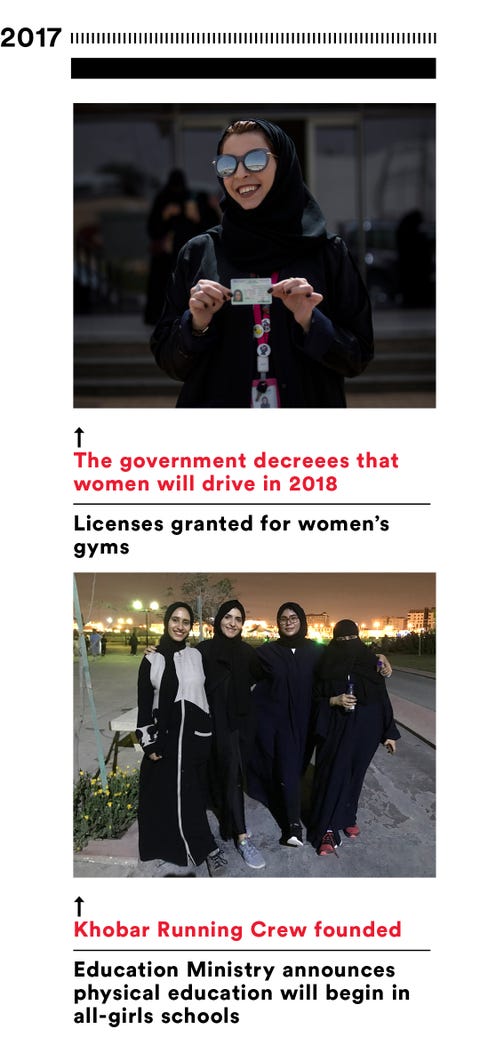

Candor like this isn’t limited to the country’s youth—Saudis talk openly about their culture, religion, and reforms (many women told me that the air changed when the government announced in September 2017 that women would drive), along with the more delicate matter of guardianship. The harsh reality is that Saudi women only have as much freedom as their families allow.

“My father was open-minded,” Nesreen tells me. “He believed in education and equality. I lived with no restrictions.” A woman in Nesreen’s office, however, lived freely until her father died, and now her brother prohibits her from traveling. Al-Batool Baroom, 36, a JRC member since 2016 and commercial director of women’s fitness chain Studio55, says that she, too, can make her own choices. But Studio55’s founder, Fatima Batook, had to wait two years for her brother to give her permission to marry the man she loved.

Most women I interviewed run with the full support of their families. But one woman, who asked to remain anonymous, runs with JRC Women despite her parents’ disapproval. Another says she chooses not to share that she runs in the streets, and sometimes with men, for fear a male family member may try to stop her.

“Some women feel like hostages to their guardians, and I find that appalling and unacceptable,” says JRC member Mohammed AlQatari. “On a personal level, my wife and kids, including my 15-year-old Maria, have complete freedom to decide for themselves—travel, study, friendships. I am here to guide, not confiscate her right to choose.”

Mohammed, like many runners I spoke with, hopes to see women’s freedoms fully restored in the law on a faster pace. Islam teaches equality, he says, pointing out that one of the Prophet Muhammad’s wives led an army after his death, riding alongside tens of thousands of men. Nesreen tells me, “In the days of Prophet Muhammad, peace be upon him, women were treated equally.”

The Saudis I spoke with were quick to disconnect Islam from their country’s practices. “How we live in Saudi is based on culture, not religion,” Raghad says one afternoon over coffee at a cafe with me and Arwa. “Whoever put these rules in place may have done so in the name of religion, but that by no means makes them Islamic rules.” She cites the abaya and driving as examples. Modesty is a tenet of Islam, but it doesn’t stipulate that women must wear abayas. Similarly, women drive in other Muslim nations, she says.

“And the ban on women’s sports?” I ask.

“That’s the old mentality,” says Arwa. “But it comes from the top. If the rulers say something”—that women will drive or participate in sports—“people trust them and accept it.”

In my last week in Jeddah, on Tuesday Hustle night, Mohammed and I pull up to a gas station next to an expanse of empty lots. Young men and women hover around cement blocks in the semi-darkness, looking more like they’re ready to rumble than do intervals.

Ahmad Nasser, a lanky and eager 22-year-old, rallies the 30 or so runners for a 2k warm-up, and afterward, everyone lines up on a wide two-way street divided by palm trees, tonight’s track. Ahmad shouts “Go!” from the sideline and the mass surges off the line. Tonight’s workout is 4 x 1k. Runners sprint ahead. Some peter out before the turn, others surge from behind. I fall in behind Mohammed, who has a light, rhythmic stride, and pass him before the line. Nesreen kicks it in, surging past Raghad. Next repeat, Raghad catches Nesreen, Mohammed bolts past me. And so it goes, 1k, rest, repeat. The group groans and gasps. Saif, who ran 16k from home to the workout, claps from the curb. A few runners throw in the towel and join him.

During the final repeat, the low, melodic call to prayer sounds into the dark night. It reverberates as, one by one, men and women cross the finish and catch their breath. Someone lies sweaty on the cement. Mohammed walks over for a high five. Nesreen laughs. The group pulls close for the team shot, then climbs in cars and drives a few blocks to a food truck owned by Arwa’s husband, who, serves up burgers.

Scan Riyadh from above, and among the towering skyscrapers and wide boulevards of the Saudi capital are the walled compounds where the majority of women run. Riyadh is the country’s religious and political center, and the pressure to follow tradition is strong. While the city’s first women’s group, Riyadh Urban Runners, began running on a public walkway in late 2016, most female runners still prefer logging miles inside compounds, largely exempt from Saudi social norms, or inside walled female college campuses, where women can run without abayas.

“Women’s running is an emerging scene in Riyadh. We have women who like running, but are anxious to run in public,” says Amal Maghazil, 31, a mom and speech pathologist who heads Riyadh Urban Runners. The handful of female runners I speak to in Riyadh’s Diplomatic Quarter—a sprawling and walled-off complex of embassies, schools, housing, and restaurants—have no interest in running the streets just yet. “I’m waiting for society to be ready,” says Rehab, 33, a university lecturer who preferred not to give her last name.

“We have a collective society, which emphasizes the group over the individual—acting outside deep-rooted gender roles can put you outside the group,” says Mezna AlMarzooqi when I meet her on KSU’s female campus in Riyadh. Mezna’s dissertation examined activity levels among Saudi female college students, and 94 percent of the women she surveyed were insufficiently active, citing social and family beliefs as the primary reason. “That’s why campus is a good place for women to start running,” she says. “Inside, we’re not breaking any social norms.”

Mezna felt the tug between her desire to run and also wanting to respect her culture. She began a walk-run program in Australia while getting her Ph.D., and the first time she ran an entire 5K, she was elated. “This was the highest happiness of my life, even now, after running marathons and climbing mountains,” she says. While she was in Saudi Arabia in 2015 to conduct research interviews, female students told her their families wouldn’t let them walk in the street without a guardian, or that they were afraid to walk alone. “I felt sad for the girls—then I realized I was one of them,” she says. “In Saudi, I didn’t have the freedom to head out my front door.” But it occurred to her she could run on campus, and she set out one afternoon for 15K. “The women clapped for me, and I knew I wanted this for others.”

In February, Mezna founded KSU Movement, the first women’s running initiative at a Saudi university. I line up with 30 or so students doing a 5K that day and she sends us off for three one-mile loops around campus. I run with Dana Amlih, a 19-year-old with round glasses and a wide smile. She’s blown away when I mention Jeddah’s sports abayas. “There is a sports abaya?” she says, her eyes wide. We climb a small hill and Dana and I give in to the effort and walk, then run again. She tells me she joined KSU Movement because she wants to run a marathon. When I run a loop solo and reconnect with her, she’s amazed I didn’t have to walk and drills me about training. I tell her about Riyadh Urban Runners, that they’re running in the streets. She grins, and I can see her mind turning.

After the run, I sit with a 20-year-old nursing student who used to dream of running in other countries because she couldn’t run at home. Her parents said it was Aeeb, a taboo, something one cannot do in front of men. They did, however, give her permission to run with the campus group. An animated young woman eager to get out of the gym, she ran outdoors only for the second time the day of my visit. “I love being outside, being free,” she says.

I tell her about Riyadh Urban Runners, too. “I would like to see women running in the streets; it is my dream!” she says, smiling. “I want to race, too. And do karate. I want it all.”

Somaya AlGhazali hops out of an Uber in a black abaya, her face snug in a hijab. She is 25, a graphic designer, and founder of Khobar Running Crew, the Eastern region’s only women’s running club. She embraces me as if I’m a long lost friend. We are meeting for the first time.

It’s evening and men work out on the outdoor fitness equipment on the corniche in Khobar, a small city on Saudi’s Persian Gulf. Khobar is part of the Dammam metropolitan area, home to Saudi Aramco, the state-owned oil company that brought a mass of foreigners to the region in the 1960s and ’70s. The influx has placed the city culturally between more open Jeddah and more conservative Riyadh.

Somaya and I run along the promenade, the gulf water just visible in the dark. Two to four women ran with her this spring, but tonight it’s just her, a sign of the group’s nascence. Somaya began running the corniche solo in 2014 after her mother died, and now divides her life into “before running” and “after running.” Describing what running has given her, she says, “I focus better, think better, sleep better, and feel in control as a person.” After being featured as one of the country’s few female runners in Destination Sharqiya, the regional magazine, women requested she start a club. She put the word out, and friends began joining her in October 2017. Few returned.

“They hated running in abayas,” she says. “It was difficult for me in the beginning, too, but you find a light one that’s shorter than most, and you get used to it.”

The Khobar corniche shows signs of the changing times. Construction is ongoing to extend the promenade north, part of the government effort to provide more recreation space. Earlier that day, crews were setting up for a car show for women, complete with driving simulations. The country held the first official women’s race on city streets in the town of Al-Ahsa, about 300 miles north of Khobar, in March, and more than 1,500 women ran, all in black abayas, many in niqab. When a video of it went viral, it garnered angry comments like “God will ask you about this vulgarity,” and “Our conservative society has begun to slip away, and its moral decline is infused with Western ideas.”

Every runner I speak to in Saudi Arabia, though, is focused on the overwhelming positive response women’s running is receiving. That energy is in the air in Khobar. Veiled women give me the thumbs up as I run solo; another woman stops me and is delighted to learn about the Khobar crew. This is the revolution. “Come, join us, change your life,” Nesreen would say.

When Saudi women talk of the future, they see women’s running growing—more women, more races, more choices. Already, JRC, Riyadh Urban Runners, and the Khobar crew have formed The Running Collectives, a nationwide umbrella group. And the Riyadh Half Marathon, which held its first race for men this past February, has announced a women’s race for 2019.

Some even predict that running in abaya will be optional in six months. “But we don’t want females running in sports bras,” says Nesreen, summing up the view of most women I spoke with. “We are Muslims. Modesty is good.”

Saudis will tell you the current reforms are helping to push the country further into the modern world—or back to the true equality of Islam, as some suggest. This excites the runners. Mohammed says nothing is sweeter than knowing his daughter is growing up with the freedom to run. Nesreen’s son Saif tells me the expansion of running, cycling, and triathlon is giving boys and girls in his generation more to do besides sniffing glue, a former time-killer for him and a friend.

“The story is about more than running,” Nesreen says. “When you run, you search for yourself, find yourself, improve yourself.” She believes this is what’s happening to the Saudi people, and by extension, their country. “Running is learning you can do more and be more,” she says, “and it has no gender.”

Forty-five minutes after leaving Jeddah, Nesreen’s driver slips off the freeway and turns down an unmarked dirt road in the Hejaz Mountains. Silhouettes of the barren peaks we’ll be racing on come into view. We pull up to a clearing, and people in shorts, leggings, caps, and hijabs hover under white tents, picking up numbers, pinning on bibs. Runners dash off behind a just-high-enough dirt mound to pee. The flags of the Hejaz50 catch the breeze.

Nesreen jumps out of the SUV, leaving her abaya on the seat, and rushes toward registration. We’re late, and as one of the organizers, she’s got the race T-shirts.

As the sun rises over the mountains, competitors line up for the fourth running of the 50K, a solo race or relay with four loops in each cardinal direction. Among the 159 competitors are Nesreen, Raghad, and dozens of other women, none in abayas, all covered to their personal level of comfort. They’re lined up with men, ready to run with the freedom they hope to feel in the city streets soon. The field surges off the line.

Nesreen puts on headphones and Raghad begins at a slow jog; both are a part of relay teams. Saif is ahead, tackling his first ultra. Light clouds overhead disappear and the temperature begins its ascent as runners climb the day’s toughest hill, SMF (Sexy Mother F**ker, named after music legend Prince).

By the time the runners head to the south loop, it’ll be 85 degrees Fahrenheit; when they hit the west loop, 100. Relay runners sprawl under the Bedouin-inspired tent, shoes off and nibbling salty snacks. Heads emerge to cheer on runners passing through or to sign the cardboard map of the world showing the 31 countries represented that day. Some snap shots in the Hejaz Ultra Instagram photo booth. Others read the Islamic prayer for travelers.

I follow Nesreen, who’s done with her first leg, as she keeps an eye out for Saif. “We have this sense of freedom here, and choice, really,” she says of why JRC women love running and racing in the mountains despite the heat and hills and dirt. “It’s because it’s the real deal,” she says. “You do it under your rules. You finish, overcome something, and you’re not the same.”

Soon, we see Yossra Ifaoui, 35, a Tunsian who was raised partially in Saudi Arabia, sprint alongside her teammate Raghad as she finishes her leg. JRC runner Amira Bahaaldeen smiles over the line, finishing. U.K. runner Eugene Galvin completes his segment and tags Nesreen. She sets off toward the east to run the fourth and final leg, dressed in black leggings and a blue T-shirt, her curly hair bouncing as the desert dirt dusts up and the sun beats down.

What They Run In

Nike was the first brand to invest in the Middle East's new running groups. "The JRC and JRC Women are powered by Nike. They provide shoes and shirts for crew leaders," Nesreen says. That sort of support has made Nike's Pegasus, Vomero, and React favorites among Saudi runners.

Image credits: Olivier Morin/AFP/Getty Images (2012 Olympics); Courtesy Jeddah Running Collective (JRC); AFP/Getty Images (2015 Voting); Jewel Samad/AFP/Getty Images (2016 Olympics); Gehad Hamdy /Picture Alliance via Getty Images (Woman with Driver's License); Courtesy Khobar Running Crew (Khobar Running Crew); Ali Al-Arifi/AFP/Getty Images (2018 Soccer Match)