Mare of Easttown’s finale was a great hour of television, but it still left many of us wondering—did we just watch a detective show about a murder investigation, or a show about female relationships and the unwinding of loss, or a show about both? And if so, why has this framing device—using a murder mystery as a vehicle to explore stories about women and mothers—become so ubiquitous? Is it just the cold hard math that complex, layered stories about women need a murder to sell the plot, a sort of “come for the crime and stay for the drama” approach? Or is that the conventions of the detective show allow a different kind of freedom, a subversive lens to tell women-centered stories?

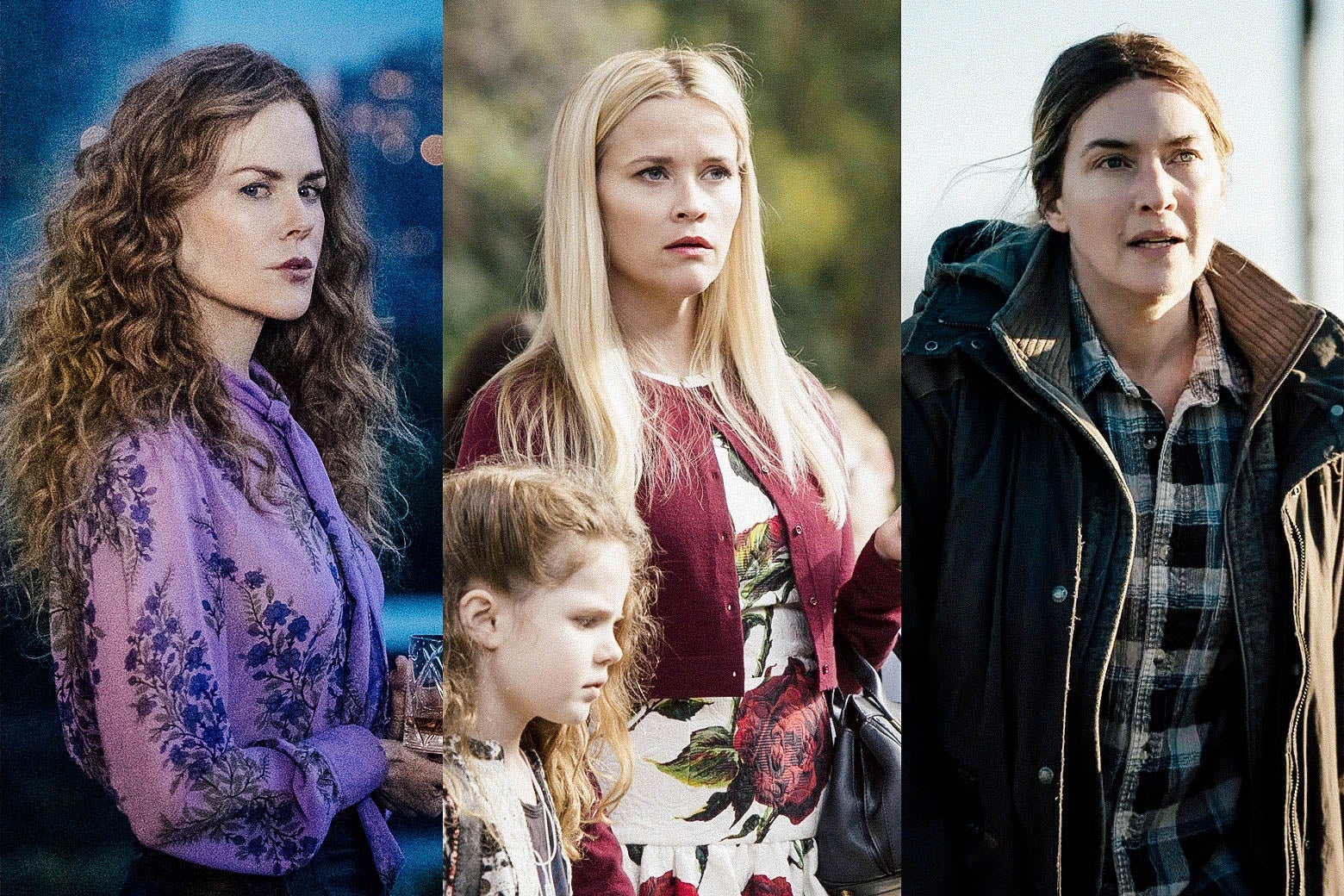

HBO has made a cottage industry out of this theme in recent years—starting with Sharp Objects followed by the monster hit Big Little Lies, and then with last year’s The Undoing and now Mare. Actors who can still legitimately be called movie stars flocked to the lead roles—Amy Adams, Reese Witherspoon, Nicole Kidman (twice), Kate Winslet. And how well these shows stuck the landing often had to do with how they delivered on the expectations set up by the murder mystery, even if the series’ interests lay elsewhere.

Mare’s atmosphere and pacing in its early episodes fell firmly in the camp of detective shows like Broadchurch—dramas that used a murder investigation as a way to explore the unremarkable and riveting details of small-town life. Kate Winslet’s Mare Sheehan doggedly follows leads in the murder investigation of a teen mom, Erin McMenamin, but there is no crazy evidence board of pins and strings, no late-night montages poring over files at the office. She cares about her job and solving the case, but the universe the show occupies is decidedly earthbound. The investigation feels more like a plot device to examine all the ways that the relationships in Mare’s down-and-out Pennsylvania town intersect and fold back on each other. We learn that Mare’s son committed suicide two years ago, and the question the show asks is: Can you process grief surrounded by people you’ve known your whole life? Are you allowed to change when you share a past with everyone you know?

This is the slow-burning territory Mare explores until the show takes a hard left into Silence of the Lambs territory, and from there, things actually get crazier. When Mare’s partner—the appealing detective Colin Zabel, who’s soft on Mare—is killed in a shootout with a man who’s been keeping kidnapped girls in his attic, I can honestly say it was the most shocking, out-of-nowhere onscreen death I’d seen since Leonardo DiCaprio in The Departed.

Shows rise and fall based on whether viewers can accept what they see on the screen, even if they don’t like it. This twist felt crazy, but not unearned—we’d been hearing about a missing girl from Easttown, Katie Bailey, since the first episode. The challenge to shows like The Undoing, which cleverly uses the voyeurism that accompanies high profile murder cases as a way to poke around the lives and living rooms of very wealthy New Yorkers, is that it fancies itself a whodunit when it isn’t.

The Undoing is more interested in exploring what happens when you can’t trust the people you’ve built your life around, and it probably would have experienced less backlash if the show had fully leaned into that theme, instead of dangling semi-plausible suspects before revealing the killer was the person we thought it was all along. What makes this show fascinating is that the brutal killing of a mother at an elite private school in Manhattan is not the scariest thing about it, not even close. The most terrifying thing is that the protagonist, Grace Fraser, played by Nicole Kidman, is not married to the man she thought she was.

That moment spools out slowly. The first episode, beautifully shot, glides around New York City like a greatest hits album—gorgeous Fifth Avenue apartments, establishing shots of the Central Park reservoir, the interior of The Frick, and an internet-captivating parade of winter coats. Grace and Jonathan (played by Hugh Grant, whose talent for playing cads is an untapped goldmine) are in the sweet spot of a long marriage, familiar with every facet of the other person and yet still managing to like each other.

Then it all unravels. When Grace hears about the murder at her son’s school, she cannot reach Jonathan, who is at a medical conference. When she calls his hotel, they have no record of him. It is a moment that demolishes the trust that makes any marriage or relationship work. You have to be able to believe your partner is on a business trip when they say they are on a business trip. Strip that away, and you have nothing. Does it matter that Jonathan’s initial lie exposes the lie that he has been fired for having an affair with the parent of a patient, the same woman he murders? I suppose. But do we have to wrap this betrayal in a murder mystery in order to face such an unremarkable, terrifying truth?

What The Undoing understands is that if you take away the murder plot, you are left with the story of a wealthy woman whose husband has been having an affair and lying to her. And so what? By making it a crime drama, the show builds the dramatic stakes, even though the questions of how well we know the people we love is more relatable to audiences than getting swept up in a homicide investigation.

Big Little Lies understands this as well. A show that focuses on a group of yoga-toned moms living in beautiful homes in Monterey, California wouldn’t seem like an obvious choice to challenge our assumptions about trauma and domestic violence, but it does, in large part because the murder mystery signals it isn’t just a frothy satire about Type A parenting. Similar to the way Sharp Objects—where Amy Adams plays a reporter sent to her hometown to cover the story of a murdered girl—shakes up our notions about what kinds of women commit crimes, Big Little Lies peels away misconceptions about domestic abuse. Nicole Kidman is extraordinary as Celeste Wright, a former high powered First Amendment lawyer who finds herself unable to leave a destructive, violent marriage. And because you spend a good chunk of the first season trying to figure out who has been killed rather than who committed the crime, Big Little Lies sidesteps the trap The Undoing falls into.

In all of these shows, the murder plot acts as both cover—giving writers room to tell complicated stories about women while still adhering to a recognizable format—and an essential ingredient. Sensationalist attic detour notwithstanding, Mare’s home stretch confirmed it was the kind of show it told us it was all along. Yes, the finale churned through multiple red herrings before it got to the real killer, but even so, we weren’t watching a nail-biting hour about a cop getting her man. We were watching a story about a family imploding, and Mare’s reluctant role in it. It just happened to be wrapped in a pretty good whodunit.

Even Mare of Easttown’s showrunner Brad Ingelsby was surprised at how obsessed viewers were with the murder mystery. But the finale works because it is both genuinely surprising that the killer is Ryan Ross—the 13-year-old son of Mare’s best friend, Lori—and devastating in a way that honors the themes of the show.

Ryan accidentally kills Erin while confronting her for having an affair with his father, and when Mare figures it out, you see her gasp in anguish. She has known Ryan his whole life; she knows Lori lied to her to protect him and that, as a mother, she would do the same thing. And yet, she doesn’t hesitate. She doesn’t go to Lori for a cup of tea to tell her that she knows. She heads to her house to arrest her son.

This surprised me. In a way, by dialing the stakes up to an 11, the show forces us to reckon with its themes of mercy, friendship, and loss. What does it mean to truly forgive someone when you blame them for taking your son? What are the limits of friendship when a girl is dead? I appreciated the way Mare took these questions on, and I also kept wondering what kind of show it would have been without the murder plot.

Would we have allowed ourselves to relate to Erin, to look at all the ways we fail teen moms in places like Delco, if she wasn’t the murder victim? Would the grimness of Easttown—hollowed out by the opioid epidemic, poverty, crime, prostitution—have been overwhelming if we were forced to watch it as straight drama, rather than the gritty backdrop of a whodunit? Certainly Mare’s identity as a detective is central to her character, and perhaps the show would not have worked without that.

While I want more stories about women that are considered high stakes on their own, even I have to admit that I’m more drawn to series like The Undoing than domestic dramas. Which means we have to ask the question: What stops us from just looking at our lives as they are?