The use of electroconvulsive therapy to treat serious mental health problems is more prevalent in women and older individuals, researchers have found.

The study, which looked at data from a group of NHS trusts in England between 2011 and 2015, found that, on average, two thirds of recipients of ECT were women, and 56% were people aged over 60.

The results chime with findings from the annual dataset release by the Royal College of Psychiatrists, which reveals that for 2016-17, 67% of patients receiving acute courses of ECT were female, as were 74% of those receiving ECT to prevent relapses – so-called “maintenance ECT”.

The data also found the mean age of patients was 61 for those receiving acute ECT, and 66 for those receiving maintenance ECT.

“This is remarkably consistent over a long period of time and in almost every country where it has been studied,” said John Read, professor of clinical psychology at the University of East London, and co-author of the latest study, published in the journal Psychology and Psychotherapy: Theory, Research and Practice.

Early this year, a Guardian investigation revealed that, while ECT has been in decline since the latter half of the 20th century, the trend now appears to have stalled, with recent figures even suggesting a slight increase in its use.

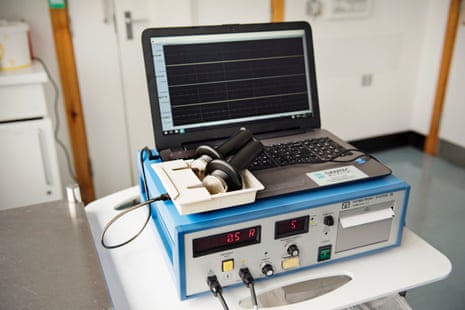

Used to treat serious mental health problems, including life-threatening and treatment-resistant depression, ECT involves passing an electrical charge through the brain to trigger a seizure. The patient is under general anaesthetic at the time, and the electricity is applied for a matter of seconds.

While some experts say that ECT is an important and powerful tool for treating certain mental health problems, others argue that more research needs to be done to understand how it works, and whether it is truly effective compared with placebos.

Patient stories are also mixed: according to the latest data from the Royal College of Psychiatrists, more than 72% of patients receiving acute ECT were rated as being much improved, or very much improved, at the end of the treatment, while fewer than 2% were deemed worse.

That ECT is more commonly used among women and older individuals was of concern, said Read. “Nobody talks about it, or tries to explain it, or wonders why that might be,” he said, stressing that ECT does not tackle the social issues behind why more women than men appear to have depression.

“[ECT] is part of over-medicalising of human distress,” said Read, adding that some studies have shown that the side-effects of ECT, primarily related to memory loss, are worse for women and older people. However, Nicol Ferrier, emeritus professor at Newcastle University and chair of the ECT committee at the Royal College of Psychiatrists, said that analyses of multiple studies had not found the cognitive side-effects from ECT were worse among elderly people or women.

The higher rates of ECT use among women and older individuals, added Ferrier, was neither surprising nor a cause for concern.

“Depression is more common in females than males,” he said, noting that the ratios were particularly high for treatment-resistant forms of the condition.

While Ferrier noted it was likely there were many factors behind that trend, he added that ECT appeared to be particularly effective for people with severe depression with life-threatening symptoms, psychosis and certain other diagnoses, and even more so among elderly women in this group. What’s more, he said, rates of ECT had declined among adults more generally, rather than older people.

“One of the reasons, we think, is that use of antidepressants is associated with quite a lot of side-effects in the elderly, whereas ECT is actually really very safe and straightforward in the elderly – provided you do it with appropriate standards,” he said.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion