Rachel Morrison’s Academy Award nomination in the best cinematography category is a landmark for women in film. This shortlist has long been the toughest Oscar ceiling to crack, but now, for the first time since the awards began in 1929, a woman has been included. Morrison, who shot the overcast landscapes and intimate interiors of 1940s drama Mudbound for director Dee Rees, stands a good chance of winning, but women in her field may be forgiven for celebrating already.

The American Society of Cinematographers (ASC), which counts Morrison as a member, was founded in 1919. It didn’t invite a woman to join until 1980, when it admitted Brianne Murphy, reportedly the first woman to work as a cinematographer on a major Hollywood studio film (Fatso, directed by Anne Bancroft). As of 2015, Deadline reported that just 4% of the ASC’s members were women, and last year, the society gave its president’s award to a woman for the first time. The recipient was Nancy Schreiber, the fourth woman to join the ASC, in 1995. She told one magazine: “I remember the first time that I walked into the ASC, I wasn’t even sure there was a ladies room!” Now she is part of the ASC’s Vision Committee, an initiative to promote greater diversity in cinematography.

The cinematographer or director of photography (DP) is the director’s right hand on set. It’s a demanding job, combining artistry, advanced technical knowledge and team management, as the DP selects the camera, lens and lighting for each shot, and commands a crew of electricians and camera operators. A good cinematographer works closely with the director to achieve the desired visual effect in each scene. A great one imparts their own unique vision to the film. Evocatively, cinematographer John Alton described the trade in the title of his 1949 book, as “painting with light”.

In the early, experimental days of cinema, there would be no distinction between director and cinematographer. Directors would turn the camera handle as they coached their actors. Things didn’t need to get much more complicated for the role to divide, though, and we know that some of the first camera operators were women, in an era when film-making was a case of everyone in the studio mucking in to get the job done. At the turn of the 20th century in Brighton, England, Laura Bayley operated the camera for her husband George Albert Smith. Georgette Méliès turned the handle in her father George’s studio in Paris in the early 1900s.

As films became more complex, with studio lighting, camera movements and multiple setups, the role of camera operator became a full-fledged cinematography job. We know that women took on this role. One book names the first credited female DP as Italian Rosina Cianelli, who shared duties with her husband on Uma Transformista Original (1915), but there are earlier examples mentioned in US magazines. We also know that from the outset, female cinematographers were considered an outlandish sight. Women held many jobs in the silent film industry, but mostly the less visible roles such as writing and editing. Although, cinematography was barely two decades old magazines found the idea of a woman operating a camera to be at best a novelty, and at worst, freakish.

“How many of you have ever heard of a woman camera man?” asked Picture Play in 1916. “That such a person exists will doubtless be a surprise to the majority of people in the film business, as well as those outside it.”

The writer AJ Dixon pretended astonishment at finding former actor Grace Davison operating a camera on a Long Island film set, even achieving trick photography effects. “I concluded that something must have happened to the regular cameraman, and that they had been forced to substitute this girl at the last moment; and I began to picture static, out-of-focus, under and overexposed negative as the result.” After diligently examining Davison’s work, Dixon was eventually satisfied that she could handle the job (“The photography was as clear as a bell, and the detail was very sharp, and some of the effects were really beautiful”). Regardless, Davison returned to acting, and later set up her own production company. That piece was titled The Only Camera Woman, but actually Davison had colleagues and predecessors, all regularly described in much the same bewildered fashion.

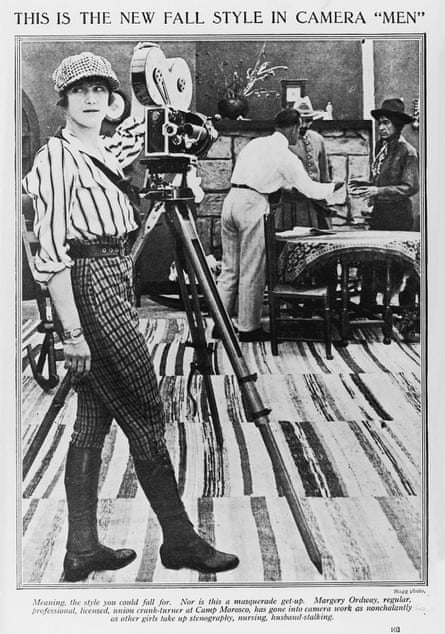

In 1914, Photoplay’s Katherine Symon found Francelia Billington operating a camera: “A brown-haired, gray-eyed, olive-skinned girl of remarkable grace and extreme prettiness standing back of one of the big cameras, turning a crank.” Billington described herself as a ”camera fiend” from childhood but conceded: “I suppose that it is still a novelty to see a girl more interested in a mechanical problem than in make-up.” Two years later, Photoplay published a picture of Margery Ordway on the set of William Desmond Taylor’s Her Father’s Son, captioning her in her working outfit of cap, blouse and trousers as “the New Fall Style in Camera ‘Men’. Meaning, the style you could fall for.” The text further explains that this isn’t a “masquerade getup” and that Ordway is a “regular, professional, licensed, union crank-turner” who has “gone in to camerawork as nonchalantly as other girls take up stenography, nursing, husband-stalking”.

Striking as they were, female cinematographers seemed easily forgettable. Moving Picture Weekly heralded Dorothy Dunn with the words “Enter the camerawoman” in 1917, and as late as 1920, Photoplay labelled Louise Lowell “The First Camera-Maid” – both women shot newsreels professionally. These awkward phrases underline the fact that camera operator is one of the few jobs on a film set to be stuck with a gendered title: “cameraman” has persisted for as long as “script girl” and “best boy”. Despite Moving Picture Weekly gamely using “camerawoman” a few more times, the old form has stuck, meaning that a woman wielding a camera continues to be seen as the exception rather than the norm.

Perhaps this image problem is why, while women such as Murphy and Schreiber, as well as many others including Sandi Sissel, Agnès Godard, Caroline Champetier and Nina Kellgren, have been working successfully as cinematographers for decades, it has taken so long for the Academy to take notice. If you find it hard to imagine a woman lifting a camera, perhaps you can’t imagine her lifting an Oscar, either.

In the 21st century, however, more and more women are excelling in cinematography. Ellen Kuras, for example, has regularly collaborated with Spike Lee and Michel Gondry – she photographed such distinctively shot films as The Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind and Summer of Sam. Recent critical successes The Levelling (Nanu Segal), Hidden Figures (Mandy Walker), The Neon Demon (Natasha Braier), Fences and Molly’s Game (Charlotte Bruus Christensen) all had female cinematographers.

In the US, female collective Cinematographers XX was founded as a way to make women in the field more visible. The names of experienced DPs are listed on a website with links to their work. In the UK, Illuminatrix works on the same principle, and there’s also the International Collective of Female Cinematographers, who “provide each other with community support and industry advocacy”. There’s no longer any excuse to argue that female cinematographers are hard to find.

If Rachel Morrison does stand at the podium on Oscar night, hopefully that will create the new popular image of a female cinematographer. Holding an Oscar is always a good look.