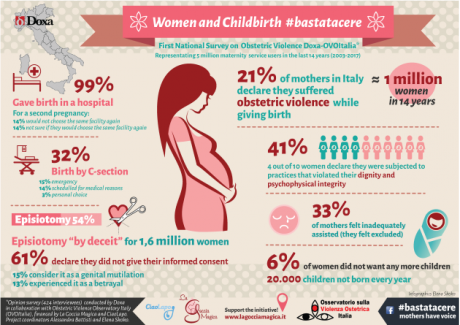

Credit: Obstetric Violence Observatory.

Eight years ago, Alessandra Battisti’s water broke. She walked into a hospital in Rome, confident that she would receive quality care. Several days later, she left the building in a wheelchair. She was in severe pain and struggled to lift her newborn daughter.

“I had a regular pregnancy,” Battisti told me. “Before the birth, my gynaecologist advised me to sign a contract with the hospital. He [said] it would ensure I was admitted... to be cared for by a qualified team and have continuity of care during the birth. So I did it.”

But it didn't go according to plan. Battisti had entered the hospital with regular contractions but doctors soon gave her oxytocin to speed up the birth. She says this was not explained, and that she wasn’t asked for consent.

Only two hours later, they were preparing for a cesarean section. Battisti says she repeatedly asked for an explanation, but that the doctors only became more and more aggressive, denying her requests for a natural birth.

“I was terrified, I was shaking. I cried, I implored. Finally, they said there were signs of fetal suffering,” said Battisti, who underwent surgery and was only able to see her daughter six hours after the birth.

Battisti was discharged only after showing proof of payment for the intervention. For months, the new mother struggled with the physical and psychological consequences of a surgery that she explicitly refused and was, apparently, medically unnecessary.

But Battisti is also a lawyer. She did her research and recognised what she had experienced as abusive medical treatment. Then, she launched a lengthy legal and advocacy battle against seemingly widespread but little-discussed 'obstetric violence.'

‘Dehumanised treatment’

Obstetric violence is institutional, gender-based violence, suffered by pregnant women at the hands of healthcare personnel.

In a 2007 law, Venezuela said it includes dehumanised treatment, abuse of medication, and “the appropriation of the body and reproductive processes of women by health personnel… bringing with it loss of autonomy and the ability to decide freely about their bodies and sexuality.”

In 2014, the World Health Organisation described disrespectful and abusive care during childbirth – including physical and verbal abuse, refusals of care and medication, and coercive or unconsented medical procedures – as human rights violations.

Between those dates, in 2011, Battisti decided to take her own case against the hospital in Rome to court, accusing it of subjecting her to surgery against her will that was not medically required.

Her case closed four years later, with compensation finally awarded to her for damages. Battisti prefers not to say how much money she received.

“As it happens in gender violence cases, they were extremely aggressive,” she told me, about the hospital’s lawyers, who launched a (short-lived) counter-suit against her for allegedly damaging the hospital’s image.

“In absence of serious physical damage, obstetric abuse is considered normal. In other medical fields, an unnecessary surgical intervention would be considered an evident violation,” she added.

In 2016, Battisti co-founded a civil society Obstetric Violence Observatory (OVO) in Italy, with activist and researcher Elena Skoko, to empower women and press healthcare and political institutions to address this problem.

“We organised conferences and seminars, we met women with similar experiences, and we try to encourage the institutions to intervene,” she told me.

In particular, Battisti wants institutional support for a proposed law, presented in parliament last year, which would criminalise obstetric violence. “Without judicial recognition it is very difficult for women to seek legal redress,” she said.

This law was last discussed in parliament in early 2017, along with three other similar proposed laws. A smaller group of deputies has been entrusted to draft a bill based on the four proposals.

In 2015, Battisti spoke about the OVO initiative in a session of the Ministry of Health's committee about childbirth. She told me that the committee effectively said 'we have no data about this phenomenon, so it doesn't exist in Italy.'

Credit: Obstetric Violence Observatory.

“So we organised the social media campaign #bastatacere, obtaining more than one thousand posts in a few days, but it wasn't considered enough. So we gathered about 3,000 obstetric violence stories, using a web questionnaire. But they said it had no statistical value.”

Finally, they decided to organise a formal survey, conducted by a market research company with financial help from two other Italian women’s associations, Ciao Lapo onlus and La Goccia Magica.

One million victims of obstetric violence

As many as one million Italian women have been victims of obstetric violence over the last 14 years, according to the study that was published in September.

Based on interviews with a sample of 424 women, it said that one in five reported “physical or psychological abuse” during their first childbirth.

Forty percent reported some form of disrespectful healthcare. Six percent of those who reported abuse said they would not have another child.

More than half said that episiotomy surgeries were performed, just before delivery, to enlarge their vaginas. Of these, almost a third had not given informed consent.

Awareness about obstetric violence is growing. But it still difficult to find specific and comparable data about it. Even the WHO has called for support to research how to define and measure disrespect and abuse in maternal healthcare.

OECD data includes c-section rates for 20 countries, ranging from 15.5% of births in Finland to 53.1% in Turkey. But none of these figures tell us about the conditions of surgeries, or what information or choices women were given.

In recent years, thousands of women have told their own stories about abusive treatment during childbirth via social media, breaking the silence about this issue.

Since 2014, obstetric violence observatories in Chile, Spain, Argentina, Colombia and France have also conducted internet surveys to gather data.

Women who collect and share information and testimonies about obstetric violence are part of a growing movement to report and stop this abuse. But, Battisti says, it will likely be a long fight.

Support independent feminist media.Support 50.50, the openDemocracy.net section covering women’s rights, sexuality and social justice, worldwide.

Read more

Get our weekly email

Comments

We encourage anyone to comment, please consult the oD commenting guidelines if you have any questions.