Knock Down the House and the Quiet Insurgency of Tears

The new Netflix documentary makes a subtly radical argument: that the emotions of women running for office are not liabilities, but sources of power.

A scene near the end of the new documentary Knock Down the House finds Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, five days after her surprise win in the 2018 primary, visiting the landmark that would soon become her office. Perched on a ledge in front of the U.S. Capitol, the building sprawling and gleaming in the midsummer sun, the Democratic nominee for New York’s 14th Congressional District talks about an earlier visit to Washington, D.C. “When I was a little girl, my dad wanted to go on a road trip with his buddies,” she says. “I wanted to go so badly. And I begged and I begged and I begged, and he relented. And so it was like four grown men and a 5-year-old girl went on this road trip from New York. And we stopped—we stopped here.”

Her voice catches; a tear trickles down her cheek. She ran for Congress, Knock Down the House has made clear, in part because of her dad’s death. “And it was a really beautiful day,” she continues, “and he leaned down next to me, and he pointed at the Washington Monument, and he pointed at the reflecting pool, and he pointed at everything, and he said”—her voice catches again—“he said, ‘You know, this all belongs to us.’ He said, ‘This is our government. It belongs to us.’” She wipes another tear before it falls off her cheek. “‘So all of this stuff is yours.’”

A woman politician, crying on camera. It’s a striking way to conclude a film about insurgency. Women’s tears, after all, have been implicated in some of misogyny’s fondest lies: that women lack control over their emotions, or, conversely, that women are so thoroughly in control of their emotions that they use them for manipulation. But Knock Down the House, as it follows four women in their races to unseat incumbents in the 2018 midterms, presents tears—of exhaustion, of sorrow, of joy, of supporters and partners and sometimes the candidates themselves—with little fanfare and no apology. The film, its director, Rachel Lears, put it to me, is meant to explore “the nature of power,” and you can read those tears as a crucial element of that exploration. Ocasio-Cortez, taking in the gravity of the responsibility that will soon be before her, tears up because … why wouldn’t she? Given the life-and-death implications of American political power, isn’t that a fitting form of intensity?

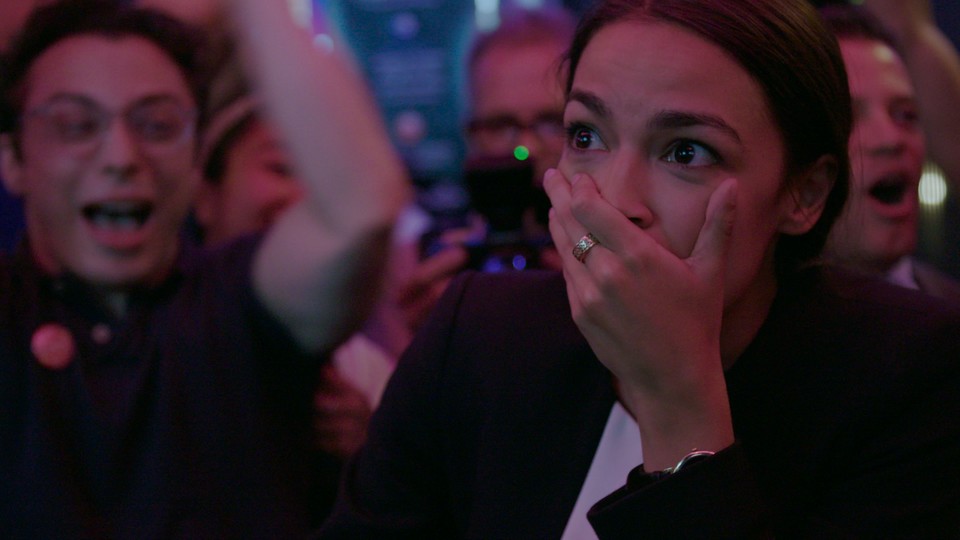

Knock Down the House, which screened at the Sundance Film Festival and South by Southwest earlier this year and became available on Netflix on Wednesday, has often been shorthanded as the “AOC doc.” This is understandable, given Ocasio-Cortez’s rise to fame (“Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez’s Superhero Origin Story Shines in Knock Down the House,” one review puts it). It is not, however, entirely accurate. The film focuses on four of the women who were recruited for runs by the Justice Democrats and Brand New Congress, grassroots organizations trying to bring progressive leadership into the halls of power: In addition to Ocasio-Cortez, there’s Amy Vilela (who ran to represent Nevada’s Fourth District), Cori Bush (who ran to represent Missouri’s First District), and Paula Jean Swearengin (who challenged Joe Manchin for his Senate seat in West Virginia). Ocasio-Cortez is the only candidate who defeated the incumbent—and the documentary’s cameras amply capture the frenetic moment of her win. (“It’s me! It’s me! That’s me on the poster!” she tells a bouncer who tries to stop her at the door as she runs into the event that has just become her victory party.) For the other women, the arcs end more abruptly. Vilela learns that she’s lost her bid, and sobs at the news.

Vilela entered the race because of her daughter Shalynne—who in 2015 had gone to the emergency room exhibiting symptoms of a blood clot and was denied full treatment because she had been unable to present proof of insurance. Shortly after that, she suffered a fatal pulmonary embolism. She was 22.

And so, that election night, Vilela told me, she was crying about much more than a lost campaign. She was crying, as well, for the infinitely bigger loss. She was crying for the parents who might be made to grieve because of the failings of a system that so often seems to prioritize the generation of wealth over the saving of lives. “When I saw that we lost,” Vilela said, “the first thing that came out of my mouth was ‘More people are going to die.’ And I couldn’t save them. Like I couldn’t save Shalynne. I felt that weight.”

That she would weep, then, at that moment—in the film, and in her life—makes perfect sense. And her tears, in turn, manage to convey a sense of all that was at stake in her campaign and in many others in 2018: the moralities of health care; the looming threats of climate change; the reclaiming of an electoral system that was theoretically built for everyone but that has generally served only a small sliver of someones.

“If anything, when you cry, you give away power,” the TV anchor Mika Brzezinski once put it. But Vilela’s tears, in their honesty and unruliness, suggest the opposite dynamic: There is power in open emotion. Knock Down the House offers a counterargument to empty stoicism and the strict-father model: The tears, here, double almost as campaign promises. They suggest the kind of passion and compassion that, the film argues, have been absent from the behavior of many of the (white, male) politicians who have shaped the status quo to their preferences. They suggest that the feminine-coded qualities that have often been treated as liabilities in political life are, in fact, profound assets. “Darn it, I want more of our politicians to care that much,” Vilela told me. “That when they’re not getting policies put in place, that they care. That it’s not just about the money to them, and the power. That it’s really about the people again.”

It’s a quietly radical argument. It wasn’t that long ago, after all, that Edmund Muskie, 1972’s front-runner for the Democratic presidential nomination, saw his candidacy effectively obliterated by a report in The Washington Post that began, “With tears streaming down his face and his voice choked with emotion, Sen. Edmund S. Muskie (D-ME) stood in the snow outside the Manchester Union Leader this morning and accused its publisher of making vicious attacks on him and his wife, Jane.” Nor was it that long ago when John Boehner’s propensity to cry in public got him widely mocked as the “Weeper of the House.”

There are occasional exceptions—last week, Joe Biden got some approving assessments of an appearance on The View that found him, among other things, tearing up when discussing grief—but in general, politicians are not expected to cry. And that is in large part because politicians are not expected to be women. In 2008, Hillary Clinton got briefly teary at a coffee shop in New Hampshire, just before the presidential primary there; the tears became a national news story, and then they became a mythology, and then, finally, they settled into an accusation: that she had manufactured them, obviously, for purposes of relatability. The whole thing suggested the punishing double bind that was as familiar during Clinton’s 2008 run as it was in 2016’s: Be authentic, but not too authentic. Be emotional, but not too emotional. Be real, but … not really.

Lears, the director, and her collaborators were aware of those tensions. Tears can be fraught things; onscreen tears can be even more so. “We were very careful in the way we presented that,” she told me; they focused particularly on the emotional arc of the story, so that the tears, when depicted, made sense to the viewer. “We wanted to make sure that there was enough context so that you … had empathy and would really understand what was at stake.” One of the film’s guiding principles, she said, came from the editor David Teague—an adaptation of a rule attributed to Emma Thompson. “Only cry once in a film, for maximum impact,” the actor is said to have advised. “Decide where it’s going to be. One weep, maybe two, but you have to be very clear about why you’re doing it.”

And so: The film shows Ocasio-Cortez choking up while talking about her dad. It shows Riley Roberts, her boyfriend, wiping away tears as the two visit the Capitol. It shows Vilela, her daughter’s urn next to her, weeping at her primary loss. “I was like, ‘You want to put what?’” Vilela said of that scene. “Can’t you just, you know, skip that part?” But she quickly changed her mind. By showing her emotions, Vilela said—by putting them at the center of the story—the film also “showed my strength.” It is a small yet sweeping reclamation.

Knock Down the House documents events from 2018, as an unprecedented number of women and people of color were elected to office; it premieres, however, in a 2019 that is still hosting dusty debates about “electability” and “likability,” the euphemisms hinting at the insidious forms backlash will take in 2020. As Americans grapple with the shape of power itself—what it looks like, what it acts like, whom it serves—Knock Down the House offers a broad and bracing vision: Imagine a world shaped by leaders who care so much, it hurts.