Marking 40 years of women in San Diego’s fire service

When she became a firefighter in 1984, Linda Morse tried hard to blend in.

The San Diego Fire Department had only about a dozen female firefighters at the time, so it wasn’t easy. Fire stations back then were built with men in mind: barracks with wide-open bathrooms and showers.

That’s why it was especially difficult when Morse needed to take a shower in the station after exercising or when she was sweaty and sooty from a fire. Hoping no one would notice, Morse would hear the loudspeaker crackle with an announcement: “Woman in the shower!”

The warning was meant to ensure she had some privacy, but she found it mortifying.

“We were so hell-bent on blending that we didn’t make noise.We put up with a lot of stuff just to blend,” said Morse, who retired in 2016 as a captain after a 32-year career. “We accepted it because that’s how it was and we didn’t want to ruffle feathers. There was so much that we loved (about the job), we were willing to put up with it.”

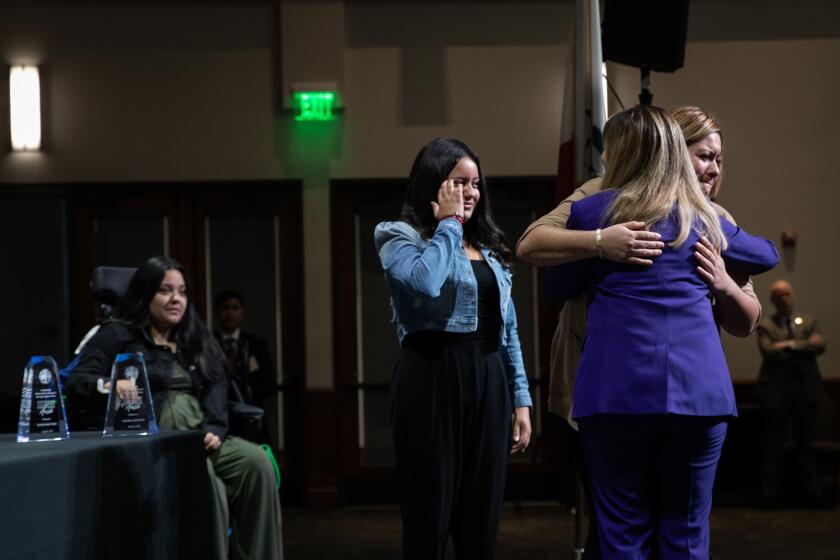

Women have served in San Diego’s fire service for the past 40 years, a milestone celebrated this month at the firehouse museum in Little Italy.

Lonnie Hider Kitch enrolled in the academy in 1977 and became the department’s first female firefighter a year later.

“I was young, so a lot of the things would roll off me,” said Kitch, who retired in 2008. “It was a good job. I was proud to be a firefighter. I loved… going out and helping the public.”

The story of women in firefighting in San Diego started a little before Kitch — back to 1974, when five women enrolled in the fire academy under a “selective hiring” process put in place by the city Civil Service Commission.

Those trailblazers didn’t get the jobs they sought, though. After going through the six-week course, all five were dismissed when fire officials determined they lacked the physical strength required.

The women sued and the city eventually settled out of court, paying them about $50,000 to divide up.

Concerns over strength requirements were still an issue when Kitch went through the academy. She ended up having to go a second time before she was hired along with academy classmate Monica Higgins in 1978.

The city ended up boosting its recruitment and hiring of women and minorities after it was sued by the U.S. Department of Justice, which alleged it was discriminating on the basis of national origin and sex in its hiring for the Fire Department and other city posts. In late 1977, the city entered into a consent decree that established a five-year hiring plan.

Kitch recalls facing an almost endless number of tests to ensure that a 5-foot-3, 120-pound woman could carry out the job’s duties.

“It was difficult for me, because every day I would go to work in training and I wouldn’t know what the captain would think up for me to do,” she said. “I didn’t know if I’d have a job at the end of the day.”

Some captains continued to test her long after she started the job, making sure she could hold onto a hose pumping out water at 250 gallons a minute and hoist heavy rescue equipment.

“They had to see me physically do these things to be comfortable I could do that in an emergency myself if I had to,” she said. “Very seldom would you have to do that by yourself -- but they still had to make sure that you could.”

Kitch wasn’t upset about having to perform such tests although “it got old after I was on for five years” and still was being tested.

Early hires did not find an easy path. Some male colleagues wouldn’t talk to the women or were openly hostile. Their firefighting gear — coats, boots, even face masks — didn’t fit right. Kitch couldn’t find steel-toed firefighting boots in her size so she wore boots manufactured for female telephone linemen. They came in red so she had them dyed black.

Fire stations were awkward setups for men and women, not designed with privacy in mind, so many of the women found ways to avoid conflicts. Some would dash off to nearby fast food outlets to use the bathroom or put on their uniforms at home so they wouldn’t have to find a place to change at the station.

Showers were always quick and usually after all the men were done.

Paper drapes went up in some stations in the early 1980s, but they didn’t provide much privacy.

“There was no way to keep people from accidentally pulling the curtain because their locker is in there,” said Lyn Lynch, who was hired in 1981. “You learned to have no privacy expectations whatsoever, or to change in the toilet room. I came to work in uniform, I went home in uniform so I wouldn’t have to bother with that.”

Lynch, who retired in 2009, said some of the men never seemed to accept women in the department.

“I found it a struggle with some of the newer men captains that would come in. Even though I was a very senior captain and had a lot of experience, they would still question me, still try to erode my confidence in my decision making,” said Lynch. “I always thought of it as a, ‘What can you know, you’re just a girl’ attitude. I think it was pervasive when I left.”

Even basic change came slowly: The badge wasn’t switched from fireman to firefighter until 1995.

Despite that, the number of women in the department grew and some began landing promotions. Tracy Jarman became the city’s first female chief in 2006, when more than 70 female firefighters were working.

That number has fallen in recent years. Out of the department’s 893 firefighters today, 45 are women.

At 5 percent, San Diego is a little higher than the national average of 3.7 percent for women career firefighters in 2015, according to the National Fire Protection Association.

“It is 2017, and you would think the numbers are going up, but they are not — they are staying about the same,” said Angela Hughes, president of the International Association of Women in Fire and Emergency Services.

San Diego Fire Chief Brian Fennessy says one of his top priorities is creating a more diverse department, one that looks more like the community it serves. A year ago, he assigned a fire captain to spearhead recruitment full time.

When the next Fire Academy begins Nov. 4, a third of the recruits — eight out of 24 -- will be women.

The department also will invite up to 100 teen girls to participate in a two-day “empowerment camp” this spring. The event is designed to show girls ages 14 to 18 that a career as a firefighter, lifeguard, paramedic or military member is an option.

“Diversity for us isn’t just the color of our skin or gender. Firefighters are problem-solvers. To get that different input from somebody’s background, their education, it is healthy,” Fennessy said.

Being a firefighter was all Dre Dominguez, 41, ever wanted to do. Her uncle and cousins were in the fire service when she was growing up.

The helicopter-rescue paramedic said she appreciates the gains her predecessors made in breaking the gender gap in the department.

“There are a lot of women in our department that laid that foundation down for us, to fight for that equal feeling at the department,” said Dominguez, who was hired in 2006.

“In my experience, if you are showing up and you are hard-working and willing and really try to do a good job… there is no reason why you should be any different than anybody else,” she said.

The latest news, as soon as it breaks.

Get our email alerts straight to your inbox.

You may occasionally receive promotional content from the San Diego Union-Tribune.