Meet 10 of the hardest working moms in history

Being a mother is tough, no matter the time period. But these unforgettable moms managed to make their mark with help from their kids—or sometimes despite them.

Before mothers like American pop artist Beyoncé and New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern were running the world, these ten trailblazing moms were wielding power, building nations, and challenging the status quo throughout history.

Sometimes being a mom requires drastic measures to do what’s best for the family—like raising an army, escaping from tyranny, or even getting a kid ahead in life with some betrayal and murder. Regardless of the era, motherhood is hard work. Here’s our list of 10 hustling moms from history.

The Rulebreaker: Hatshepsut

Rulers in ancient Egypt were male by default, but one woman changed all that. After Pharaoh Thutmose II died in 1479 B.C., Queen Hatshepsut’s two-year-old stepson was named heir, and she became regent. At least, that was the plan. Debate over the exact timing is heated, but scholars agree that Hatshepsut gradually began to rule as a king, crowning herself pharaoh within the first five years of her regency.

For 21 years, Hatshepsut ruled. She made offerings to the gods, negotiated trade, and constructed massive monuments. To solidify her position, she began presenting herself as male in artwork. Statues and reliefs of Hatshepsut depict her wearing pharaonic headdresses, attire, and false beards. A careful manager of public relations, she repeatedly proclaimed that she had taken the throne because the god Amun had willed it.

Hatshepsut died around 1458 B.C., and her stepson Thutmose III, now a full-grown man, could finally claim the throne. He tried to erase records of his kingly stepmother, but his attempts to write Hatshepsut’s prosperous and popular rule out of history ultimately failed.

The Power Player: Agrippina the Younger

Ruthlessness ran in the family—at least for these powerful Romans. By the time Julia Agrippina, known as Agrippina the Younger, was 24, she had been married for 11 years and given birth to her only child, Nero. After she was caught organizing a coup against her own brother, Emperor Caligula, in 39 A.D, she was exiled. While banished on an island in the Mediterranean, her husband died from an illness and brother was assassinated by his own troops. The new emperor, Agrippina’s uncle Claudius, welcomed her back to Rome. She then re-married, was re-widowed under suspicious circumstances (some believe she killed her second husband), and took a third husband: her uncle, Emperor Claudius.

As empress, Agrippina enjoyed more power than any Roman woman before her. To shore up her position, she successfully convinced Claudius to disinherit his biological son, Britannicus, and adopt her son Nero as his heir.

Then, ancient historians say, she turned to murder: Tacitus, Dio Cassius, and Suetonius describe Agrippina poisoning Claudius with mushrooms in order to put Nero on the throne so she could rule Rome as regent. Historians are still debating if Claudius may have actually died from natural causes. Regardless of the method, the timing was fortuitous, and Nero became emperor.

Nero became a notoriously bloody tyrant with no patience for his mother’s oversight. In 59 A.D. he tricked Agrippina into sailing on a boat that was rigged to collapse—but she survived. To finish the job, the young emperor sent three marines to her villa to assassinate her. According to Roman historian Tacitus, in her last moments, Agrippina thrusted out her stomach and commanded the killers to “strike the womb” that gave birth to their emperor.

The Rebel: Boudica

This fierce queen challenged the Roman Empire in a bold attempt to avenge herself and her daughters. It began when Boudica’s husband, the leader of the Iceni tribe in Britannia in current-day England, didn’t leave Roman officials his wealth when he died around 60 A.D., as was expected by the region’s then-rulers. Instead, he willed half of his estate to his wife and two daughters and the other half directly to Roman emperor Nero. As punishment, Roman officials publicly beat Boudica and raped her daughters.

Boudica’s tribe, men and women alike, were outraged, and she channeled that fury into a rebellion that almost drove Rome from Britain. A huge contingent of rebels and neighboring tribes—as many as 120,000—followed Boudica, laying waste to several Roman settlements. According to Roman historian Tacitus, Boudica and her daughters circled the battlefield on a chariot to inspire some 80,000 tribal insurgents during the final battle—only to have the entire force wiped out by 10,000 Romans trained for combat.

The Wordsmith: Christine de Pizan

Widowed in 1379 with three children and a mother to care for, 25-year-old Christine de Pizan decided she didn’t need a man to survive. Instead, she leveraged her formal education, a rarity for women at the time, to get a job. Born in Italy but raised in France, Christine studied Greek, Latin, literature, medicine, and philosophy before marrying around age 15. She drew on her considerable knowledge to find work managing calligraphers, bookbinders, and miniaturists at a scriptorium. For extra cash, she began sending her poems to influential figures across Europe and, eventually, gained a few patrons.

Soon she was earning enough money to quit her supervisor role and live by her own pen—and it was a rowdy pen, at that. Christine didn’t shy from writing her opinions. She argued for the education of women, explaining, “If it were customary to send little girls to school like boys . . . they would learn as thoroughly the subtleties of all the arts and sciences.” Living in the shadow of the Hundred Years’ War, she also wrote pointed advice for politicians. Christine’s last poem before her death in 1430 was in praise of Joan of Arc; she was the only writer to create a popular work about the soon-to-be martyr before Joan was burned at the stake.

The Master Planner: Idia, First Queen Mother of Benin

Oral tradition passed down from the pre-colonial kingdom of Benin maintains that Idia is the “only woman who went to war”—a title she earned when a civil war broke out between her son, Esigie, and his half-brother by a different woman. Fighting over who would be the next ruler of Benin, a kingdom that was located in present-day southern Nigeria, Esigie was victorious in 1504 and credited his mother’s counsel and “mystical powers” for his victory.

To thank her, Esigie named Idia the first “Queen Mother” (the rough equivalent of a senior chief, a role traditionally reserved for men). As Queen Mother, Idia oversaw a palace, villages, chiefs, and servants. Unlike Benin women before her, she sat on a throne, carried a sword, and wore certain red ornamental clothing and beads. Idia’s successful command as Queen Mother would provide a role model for generations of women who filled the role after her. Even Idia’s hairstyle, a curved cone covered in coral beads, would become associated with mothers of Benin’s future kings.

The Adventurer: Sacagawea

The famous Native American Shoshone guide gave birth to her first child, Jean-Baptiste Charbonneau, less than two months before setting out with Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on their expedition across North America in 1805. For nearly a year and a half, Sacagawea carried her infant son from North Dakota to the Pacific coast and back. Lewis and Clark were lucky to have them.

Sacagawea’s husband, a French-Canadian fur trader, convinced Lewis and Clark to hire the couple as interpreters to help the expedition barter with native tribes. When the team came across a group of Shoshone six months later, Sacagawea realized that their leader, Chief Cameahwait, was her brother whom she hadn’t seen in five years. The party was able to purchase the goods they needed. As the team continued on, other tribes were friendlier towards the party when the saw Sacagawea, often figuring the group wasn’t a war party if a mother and child were with them.

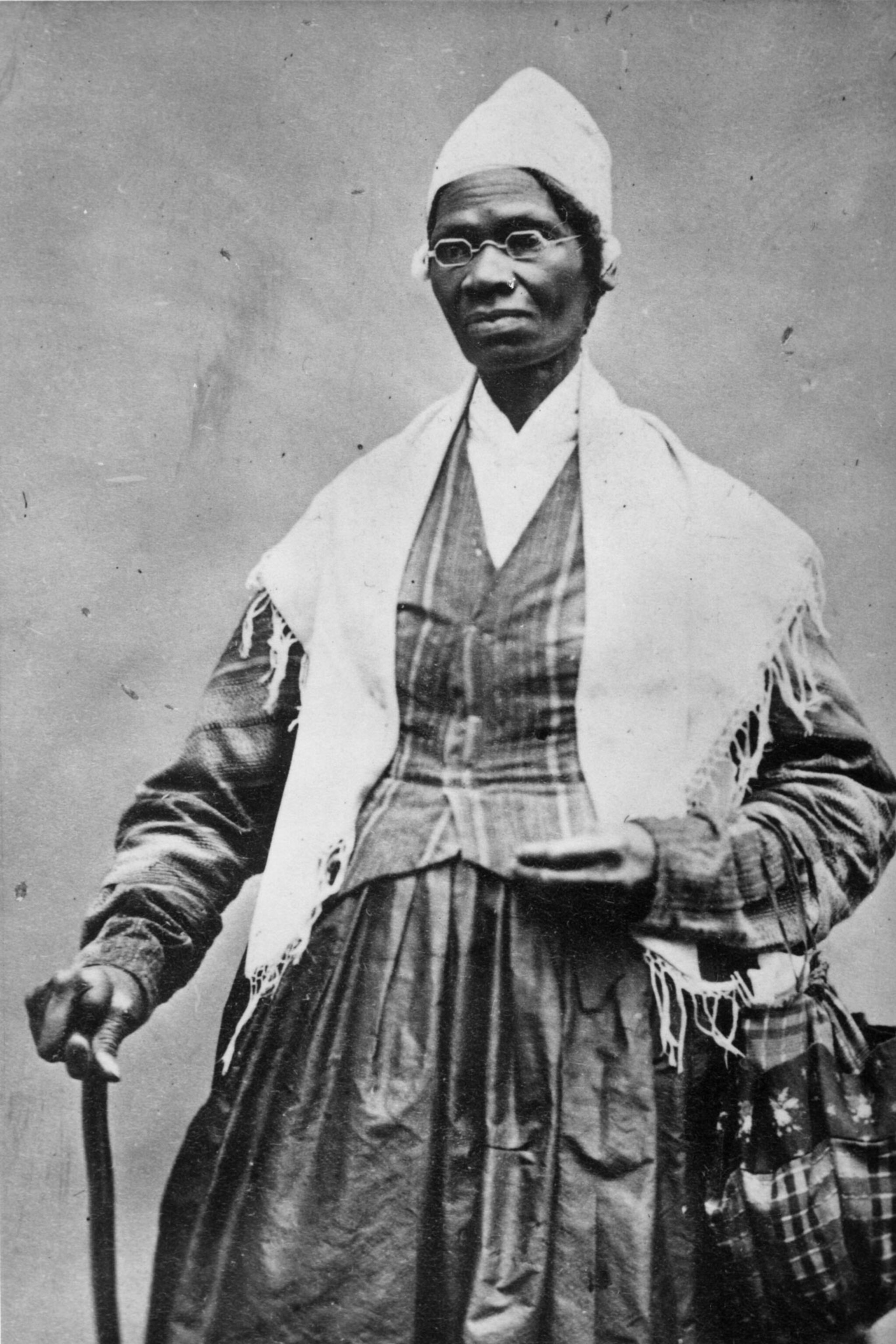

The Freedom Fighter: Sojourner Truth

Born Isabella Baumfree in upstate New York around 1797, Sojourner Truth was two years old when the state changed its slavery laws: enslaved people born before 1799, like Sojourner, would be free by 1827, and children born into slavery after 1799 would be released in their twenties (age 25 for girls, and age 28 for boys).

In 1826, Sojourner escaped to freedom with her infant daughter, Sophia but was forced to leave behind her three older children: Diana, Peter, and Elizabeth. She found shelter with abolitionists who paid $20 for her freedom, but she learned that soon after her escape, her five-year-old son Peter had been illegally sold to slave-owners in Alabama. Determined to defend her son’s rights—it was illegal in New York to sell enslaved people across state lines—she sued those responsible and won. Her son was freed, and Sojourner became one of the first black women to win a court case against a white man. It was a first step in Sojourner’s journey to becoming a prominent speaker and advocate for abolition and women’s rights.

The Advocate: Lakshmi Bai

In 1853, the childless Maharaja of Jhansi, a princely state in northern colonial India, was dying, and he and his queen, Lakshmi Bai, adopted a son shortly before his death. Jhansi royals and the British East India Company had maintained a cordial relationship, but the company rejected her adopted son as a legitimate heir and seized the territory. Lakshmi fought for her son’s right to their land: She hired a British lawyer who advised her to send representatives to London to argue her case before the East India Company’s Court of Directors. The company did not side with the queen and she was forced to leave the royal fort and reside her palace in 1854. Three years later, a series of Indian rebellions against British rule broke out in the area. As nearby violence escalated, 60 British men, women, and children sought shelter in the fortress. In no position to outlast a siege, the foreigners surrendered and were promised a safe departure, but were killed once they left the fort.

Although there was no evidence of her involvement—only hearsay and unreliable testimonies—British forces were quick to blame Lakshmi for the massacre. By early 1858, the British marched on Jhansi seeking revenge. Lakshmi Bai raised an army of 14,000, but her forces were overwhelmed. She escaped with her son and joined forces with another rebel leader, but was killed in battle in June 1858. Songs and poetry have kept her memory alive and in 2019, her bravery during India’s first war of independence was the subject of the popular film Manikarnika.

The Honored: Ann Reeves Jarvis

Ann Reeves Jarvis was such a good mom that her daughter spent the rest of her life dedicated to creating a day to honor her—and every other mother. Jarvis was a peace advocate and worked to ease tensions between Confederate and Union veterans after the Civil War. When she died in 1905, her daughter, Anna Jarvis was devastated. Memories of her mother inspired her to start a campaign to create a holiday for mothers. Anna imagined it as a day when children would honor and thank the women who had done more for them than anyone else. By 1908, she successfully organized the first Mother’s Day events in West Virginia and Philadelphia.

Though celebrations initially faced some opposition, Mother’s Day quickly gained popularity and became a national U.S. holiday in 1914. By 1920, Anna had a change of heart about Mother’s Day and felt the commercialism was corrupting the holiday’s original intentions. According to her, the industries profiting from Mother’s Day were, “charlatans, bandits, pirates, racketeers, kidnappers, and termites that would undermine with their greed one of the finest, noblest, and truest movements and celebrations.”

The Musician: Maria von Trapp

Maria Augusta Kutschera never intended to become a mother. In 1926, the young Austrian was studying to be a nun at the Benedictine Abbey of Nonnberg in Salzburg, Austria, when Navy captain and widower Georg von Trapp came looking for a tutor. The nuns assigned Maria to a 10-month stint with the family since she had a degree in education. She was there to teach one of the children, but Maria quickly fell in love with all seven. All the while, the Captain was falling in love with her. When he proposed, he asked her if she would become a second mother to his children. Maria later said, “God must have made him word it that way, because if he had only asked me to marry him, I might not have said yes.” The duo married in 1927, had two more children, and after the Depression, the family began singing professionally across Europe. When Austria fell under Nazi control in 1938, the family fled to Italy by train and eventually to the United States. Maria had one more child with von Trapp, and then wrote a memoir in 1949, The Story of the Trapp Family Singers, which became the basis for the 1959 musical The Sound of Music.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?How can we protect grizzlies from their biggest threat—trains?

- This ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thoughtThis ‘saber-toothed’ salmon wasn’t quite what we thought

- Why this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect senseWhy this rhino-zebra friendship makes perfect sense

- When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.When did bioluminescence evolve? It’s older than we thought.

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Environment

- Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?Are the Great Lakes the key to solving America’s emissions conundrum?

- The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?The world’s historic sites face climate change. Can Petra lead the way?

- This pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilienceThis pristine piece of the Amazon shows nature’s resilience

- Listen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting musicListen to 30 years of climate change transformed into haunting music

History & Culture

- Meet the original members of the tortured poets departmentMeet the original members of the tortured poets department

- Séances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occultSéances at the White House? Why these first ladies turned to the occult

- Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?Gambling is everywhere now. When is that a problem?

- Beauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century SpainBeauty is pain—at least it was in 17th-century Spain

Science

- Here's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in spaceHere's how astronomers found one of the rarest phenomenons in space

- Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.Not an extrovert or introvert? There’s a word for that.

- NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?NASA has a plan to clean up space junk—but is going green enough?

- Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?Soy, skim … spider. Are any of these technically milk?

Travel

- Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?Could Mexico's Chepe Express be the ultimate slow rail adventure?

- What it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in MexicoWhat it's like to hike the Camino del Mayab in Mexico