On a Thursday evening, the field behind Austin’s McCallum High School is mostly lost in darkness. Only a small square of grass is illuminated by three mounted tripod lights—one broken—at the 50-yard line. A neon-blue sign for Dart Bowl flickers across the street.

On the periphery of the lighting, twelve silhouettes stand in a semicircle around the lone figure in the unintentional spotlight, Coach Chenell “Soho” Tillman-Brooks, who grins and surveys the players. “Let’s give it 100 percent,” Tillman-Brooks barks.

They start with a run-blocking drill. Paired-off partners stand facing each other. One player stands tall, arms dangling, while the other stands knees bent in a squat, body coiled tight, ready to spring into action.

“Hit! Hit hard!”

The run-blocking drill continues, grunts growing louder, hits getting harder.

In the poor lighting, it would be easy to mistake the team for a men’s rec league, but the sheer number of ponytails give it away. This is the Austin Yellow Jackets, a professional women’s football team.

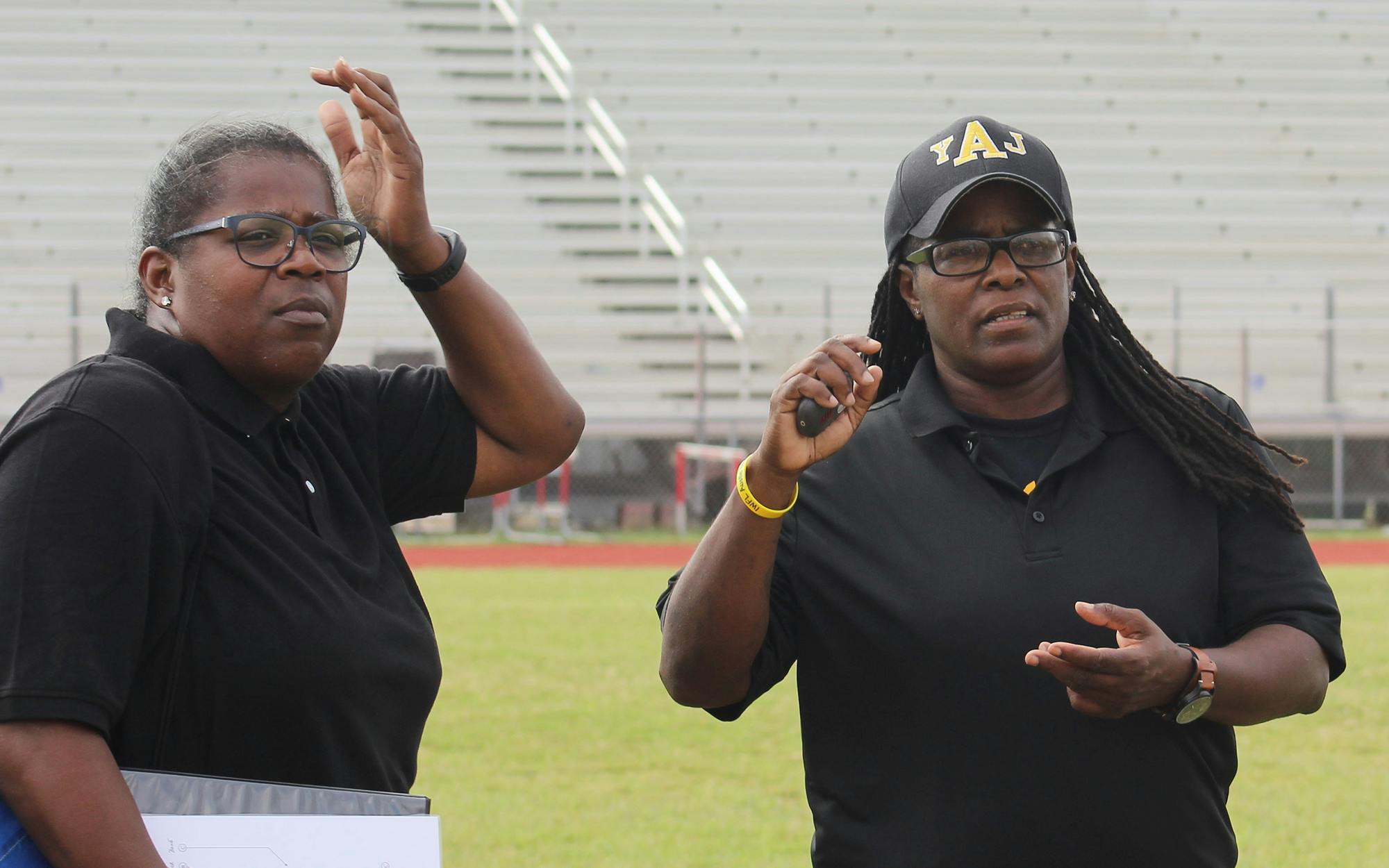

On the field is Lisa Holewyne, a former professional boxer, team co-owner, and offensive line coach for the Yellow Jackets (known as the YJs); Sekethia Tejeda, a former player who retired after eighteen seasons of professional football and now coaches the YJ defensive line; Felexis “Flex” Bryant, a 23-year-old cornerback picked up from the waiting staff of Logan’s Roadhouse; Jennifer “JT” Taylor, defensive end and American All-Star player; Toni “Tick” Fuller, running back and self-proclaimed ambassador of women’s football; and, of course, Chenell “Soho” Tillman-Brooks, a former player and the only female appointed head coach of a professional women’s football team in Texas.

The team consists of women of all ages, colors, and sizes, with one thing in common: they want to play football.

Women’s football is often associated with a certain kind of gameplay, exemplified in the LFL, or Legends Football League, formerly known as the Lingerie Football League. The LFL is a highly sexualized tackle league: players wear “performance apparel” of spandex bikini bottoms, low-cut crop tops with shoulder pads, and helmets with clear visors instead of face masks.

But that’s not the game Tillman-Brooks and her ladies play.

They play real football, just like Tom Brady, Odell Beckham Jr., and J.J. Watt. In the decades since Title IX, a law that gives each gender equal rights to educational programs and activities, including sports, the game has slowly shifted as women push for gender equality on both the sidelines and the field. There’s Kathryn Smith, a quality control coach for the Buffalo Bills and the first full-time female NFL coach. There’s Lakatriona Brunson of the Miami Jackson Generals, one of the first female high school football head coaches in the country. There are the ten women’s football leagues in the United States, as well as leagues in Canada, Mexico, Europe, Australia, and Asia, playing by the same rules and with the same level of contact as the men. And there’s the Independent Women’s Football League, a full-pad, full-contact, 11-on-11 league for women founded in 2000. The Yellow Jackets are one of 22 professional women’s teams in the IWFL and one of the few with a female head coach.

There’s hardly any difference between the NFL and IWFL handbooks: Additional measures for the IWFL prevent blocking below the waist for anatomical reasons and the ball is slightly smaller because women’s hands are smaller. Otherwise, the rules of the game are the same. But IWFL teams such as the YJs have other challenges to contend with: a lack of funding, a lack of interest, and a lack of support.

The Yellow Jackets formed in 2013 after a split from the Outlaws, Austin’s other team in the Women’s Football Alliance. Before YJs, Holewyne and Tejeda played for the Outlaws, with and Tillman-Brooks working as the team’s defensive coordinator. Their coaches were mostly men who they felt were not putting the ladies in a position to be successful or win games. Tejeda’s goal was to get a championship ring—but in the eleven seasons she played for the Outlaws, the team only won their division twice.

Finally, Holewyne decided to do something about it: She approached Tillman-Brooks about being the head coach for her new team, the Yellow Jackets. A female coach for a female team? That was unprecedented in Texas.

Along with Nancy Javaux of the Iowa Crush, Tillman-Brooks is now one of two female head coaches in the IWFL. Tillman-Brooks, who leads the only fully female coaching staff in the league, sees a clear advantage in female coaches for female players: male coaches tend to deploy practices and strategies familiar from men’s football, although female players are different physically and mentally from their male counterparts.

“In women’s sports, it makes sense to have a female coach,” Tillman-Brooks said. “You’ve got to give these women a face that looks like theirs.”

Tejeda left the Outlaws because of the coaching.

“It seemed like all the male coaches would do is yell at us,” Tejeda said. “We tried to explain to our head coach how to make our team more successful—we’d say, ‘Hey, you’re playing us in the wrong positions,’ but he didn’t want us to tell him how to run the team.”

When she heard Tillman-Brooks would be coaching a new team, the YJs, she left the Outlaws along with half the other players.

“We felt like since [the Outlaw coaches] weren’t going to listen, we were going to go where we could be successful,” Tejeda said. “We haven’t won the championship yet, but as a new team we’ve won our division twice and are undefeated this season.”

She strongly believes having a female coach has made all the difference. “[Tillman-Brooks] just knows how to communicate with us effectively,” Tejeda said. “She comes to us as a player because she’s done this herself, walked in our shoes. She’s taking us along the way she was coached and the way she wanted to be coached.”

Running back Toni “Tick” Fuller agrees that having female coaches gives their team an edge, and connects traditional and non-traditional coaching styles. “Having a woman coach is a ‘feeling’—a feeling of unconditional love and acceptance as we break barriers in a male-dominated sport,” Fuller said. “It’s a reminder that we can.”

Tillman-Brooks knows her players are grown women with kids, careers, and real adult responsibilities off the field. Unlike players in the NFL, football is not a career for these women. It can’t be—there’s no money in the IWFL. For most of the women, the team is their family and football is their escape from the real world.

On the field, Fuller doesn’t look like much. At 5’3″ and 120 pounds, she can be easily overlooked. But football means a lot to her. It saved her life.

Fuller grew up in Dallas in a broken home. With an abusive father and unhappy mother, she turned to sports as an escape from the violence. She was good at them, too: at the age of nine, she ran a relay in the Junior Olympics.

One night in an alcohol-fueled rage, her father ripped off her mother’s ear. The landlord patched her up. That night, in 1995 at the age of fourteen, she and her mom bought one-way tickets to Atlanta for $29 each. They never returned.

For five years, Fuller poured herself into sports and academics at her new school, Frederick Douglass High School. She graduated with academic honors and enrolled at Vanderbilt University on an academic scholarship. During her sophomore year of college, she found flag football—”or really, football found me,” she said.

Football was her magic. Beneath her goofy sorority girl exterior, she was angry all the time, and football became an outlet for that anger. “Football does that for me,” Fuller said. “It gives me a win even if it’s a temporary upper. I need it, I really need it.”

After graduating, Fuller sought out a place where she could continue to play and grow. She found it with the Yellow Jackets. “This team, they’re my family,” she said. “Unknowingly, they help me through life day by day, practice by practice.”

For many of the women, the team is about more than the sport. It’s not just a game—it’s their family and their getaway from any issues they might have off the gridiron. In the men’s game, it’s all about the size and strength of the players, but according to Tillman-Brooks, on this field, it’s about the size of the heart.

“Anyone who’s a realist knows women have so much more to prove than men: They have to defy odds,” Tillman-Brooks said. “Out here, they do it every day.”

Tillman-Brooks is a workaholic. She wakes up at 4 a.m. each day for her hour-long commute from New Braunfels to her full-time job as a programmer in Kyle. After work on Tuesdays and Thursdays she drives anywhere from one to two hours in Austin rush-hour traffic for two to three hours of YJ practice. On Saturdays, when there isn’t a game, she holds a three-hour intensive practice. She draws up the team’s plays from scratch every season—there’s never been a repeat playbook.

She likes to call herself a “24/7-365 coach”: when the team isn’t together or the season isn’t in, she’s thinking about or talking to her ladies.

“The biggest part of being a coach isn’t being a coach,” Tillman-Brooks said. “It’s being a confidant, an advisor, a counselor, or a much-needed shoulder.”

Tillman-Brooks’s success as head coach for the last two seasons begs the question: if female head coaches are so beneficial to a women’s team, why aren’t there more of them?

Maybe it’s because, unlike women, men are encouraged from an early age to learn and play football. Or perhaps, unlike women, men can make a career out of the sport. It could be because men are physically stronger than women. Or maybe most people think men have more experience with the game than women. Tillman-Brooks believes it’s a combination of factors: she thinks few women are confident enough in themselves to accept the challenge of coaching, and that if they do, they face a lack of support.

“It takes a lot,” she said. “Being out on the field and playing is one thing. Being on the sideline and calling the game is another.”

Tillman-Brooks remembers one especially challenging day to be a female head coach. After a victory against a coach who was a former NFL player, he refused to meet Tillman-Brooks at the 50-yard line to shake hands, as is custom with most professional football teams. Instead, he huddled his team to him and then proceeded to walk to their locker room. In passing conversations with Tillman-Brooks, coaches of other teams talked about this coach’s interactions with them as completely normal. He didn’t acknowledged Tillman-Brooks before, during, or after the game.

“Good evening and welcome to tonight’s game between the Tulsa Threat and your undefeated Yellow Jackets!” the announcer’s voice booms across the field.

The 63 fans in the bleachers, draped in blankets and scarves in the surprising 50-degree weather, cheer loudly, chanting “A-Y-Js! A-Y-Js! Let’s go ladies!”

Tillman-Brooks meets the Threat’s head coach, Cy Wheeler, and the referees in the middle of the field. She’s the only woman out there. The coaches shake hands. The Yellow Jacket players line up on the sideline, as a slight buzzing noise begins over the speakers. It crescendos until nothing but the buzz can be heard.

As suddenly as it began, the buzz ceases. Holding hands, the Yellow Jackets swarm the field. The referee yells, “Play ball!”

And so, they play.

In the second quarter a Threat player breaks away from the pack and makes it to the 50-yard line before being tackled. On the sidelines, Tillman-Brooks yells, “Who does she belong to?! Who does she belong to?!” The Yellow Jackets fight to keep the Threat from a first down. Number 1, Fuller, nabs an interception and runs 47 yards for the YJ’s first touchdown of the game.

“Touchdown, Yellow Jackets!”

The players remove their helmets as they make their way off the field. Holewyne approaches number 18, Kelly “Milk” Allen, defensive tackle/quarterback. Allen sets her helmet between her feet and hinges forward at the waist, re-gathering her long hair and twisting it into a bun as Holewyne whispers plays in her ear.

Sotonye Dikibo, number 91, makes her way to the little red Flyer wagon on the sidelines where her children have been watching her play. Her daughter stands up and cheers, “Go Mama, go!” Seeing her excitement, her baby brother mimics her clapping, gurgling in delight. On the field, Dikibo is a football player, but in between plays, she’s a mother, checking in on her biggest fans.

The other players grab water bottles and clap each other on the back, congratulating their teammates on good blocks, passes, and runs.

By the end of the game, the scoreboard reads 38-0. The Yellow Jackets are undefeated. Like at every other game, Cyndi Lauper’s “Girls Just Want To Have Fun” plays over the speaker system as the women gather their belongings and families.

“They really need a DJ for the games,” one player jokes.

Football is still largely considered a man’s sport today, but the Yellow Jackets are out to change that. Slowly but surely, women are taking over their own piece of the game. Once, a man suited up at practice with the Yellow Jackets. He left for the hospital with a busted shoulder and a bruised ego.

These women continue to break barriers by giving time and money to the game they love. They fundraise at games, with carwashes, coffees, teas, and merchandise, putting the money they make right back into their team. They continue to practice and play and win, defying odds, getting their name out there.

They hope that, soon, the struggle will end—that they won’t need to fundraise or pass a donation bucket around in the stands at games to pay for travel expenses; that they will fill a stadium with more than 250 friends and family members for games, a fraction of high school football game attendance in Texas; that their roster will list 60 names, not 25-30; that at the end of a game that they play and win, the opposing team’s male coach will always be willing to shake Tillman-Brooks’s hand. Maybe she’ll even shake the hand of another female coach instead.

As knowledge, support, and confidence grow, there will be more women on the gridiron. Tillman-Brooks is convinced of that. Until then, she will continue to coach football on the field behind McCallum High School.

A whistle chirps three times, ending the team’s jumping jack cool-down. Tillman-Brooks waves her clipboard in the air and yells, “Everybody, bring it in!”

She looks down, makes a note, and looks back up, smiling, at her players.