Nikon has a serious optics problem.

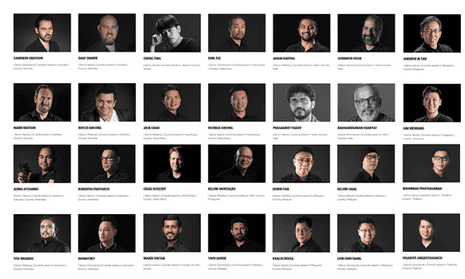

The Japanese camera giant chose 32 professional photographers across Asia and Africa to test-drive and promote its new camera, the D850. Of the 32 photographers chosen, Nikon managed to pick zero women.

What is so obvious to me – a professional photographer – as well as colleagues, photography bloggers and social media users, was not obvious to Nikon. Instead, it seemed to have worked on the campaign, from the concept stage through to development, marketing and public relations, without a thought for its female clients.

A photograph – as Nikon should know – speaks a thousand words. The image Nikon used to promote its new camera shows that companies still don’t value women in photography, and that professional photography remains a boys’ club. As one photography blog snarked: was the camera made specifically for men?

Based on its research, is Nikon saying only men are buying cameras? Or that the market for women is so insignificant Nikon has chosen to overlook them?

If that’s the case, the problem is even greater than Nikon’s omission. Photography is a reflection of our society – and if one group of people controls the narrative, millions of stories will go untold.

Female photographers in Asia or Africa, for example, are uniquely positioned to shine a light on women who have no voice or power. When I’ve worked on important and sensitive stories about the plight of women in Asia, I’ve only been able to gain access because I’m a woman. Here’s just one example from an assignment in Pakistan:

Paula Bronstein’s entire body of work – including her portraits of victims of acid violence – or Smita Sharma’s work on rape victims in India perfectly illustrate this argument. I could name dozens more.

In response to the backlash, Nikon responded, weakly: “Unfortunately, the female photographers we had invited for this meet were unable to attend, and we acknowledge we have not put enough of a focus in this area.” Women made up just 11% of Nikon’s workforce this year.

Nikon, perhaps I can help.

As vice-president of the Women Photojournalists of Washington, a non-profit created to promote the role of women in photojournalism, foster their professional success, and mentor emerging photographers, our mission is, sadly, critical. You know this already: you give us generous funds to support our mission.

With over 400 members in the DC area, our members include renowned war photographers, Pulitzer prize winners, political photographers, and video journalists covering the biggest news stories around the globe. Yet we continue to see women being sidelined.

I’d be thrilled to give your camera a go on my next assignment, as would thousands of other professional female photographers.

If you want names, please don’t hesitate to get in touch.