This essay was adapted from Meg Conley’s newsletter, homeculture. Subscribe here.

I asked for a purse for my fourth birthday. I wanted one that I could drape from my wrist when I walked with my mom as she pushed my sister’s stroller. I thought purses were for holding treasures. The treasures I had. A rock that almost looked like a crystal. A little Lucite charm I found in my grandma’s jewelry box. An old coin my grandpa gave me on my last visit to New Mexico. A Rainbow Brite pencil.

The treasures I’d find on walks and errands. The rare leaf turned red and yellow in my California fall? I could just reach down and pick it up. A bakery’s business card with a picture of a cupcake? I could just reach up and take one. I got the purse for my birthday. I don’t remember what it looked like. I can remember the weight of it.

Earlier this month, a story about a lost purse went viral. Fourteen-year-old Beverly Williams left her purse at her Texas high school in 1959. The purse was found this year, as the school was being torn down. Local historians used the items in the purse to identify its owner. Williams died years ago. Her daughter cried when she heard about the discovery. In the photos accompanying the article, the contents of Williams’ purse—a miniature calendar, a handkerchief, a telephone directory, and photos, some of which are of the girl’s “possible crushes” (as the Houston Chronicle’s article put it)—are laid out carefully in a full exhibition.

The lives of girls deserve to be taken seriously. It’s a lovely story. But there was also something about the internet’s response that left me a little restless. Would a boy’s backpack from 1959 have gotten as many retweets and press mentions? What is it about a girl’s purse that draws so many eyes?

Purses are relatively new accessories. Women used to carry their necessities in pockets tied around their waist, worn under their layered skirts. The pockets were a kind of undergarment, hidden by the thickness of a woman’s outer layers. But when skirts slimmed, the bulk of the under-pockets poked through the skirt fabric. This was considered embarrassing. A curator for the Women’s Museum of California wrote, “Pocket-lines were the panty lines of the 1790s.”

The purse was the solution for the unsightly revelation. Women began carrying little purses called reticules. Some people were scandalized, as the little purses still looked like pockets. They thought women were walking around with underwear draped from their wrists. A purse was not a purse; it was an outline of women’s most secret places.

I asked for a purse again when I turned 12. I wanted one that I could clutch at my side when I walked out the door of my house in the suburbs. By then, I thought purses were for holding embarrassing things. The embarrassing things I needed all the time. A brush, because my hair never laid flat. Mascara, because I was always rubbing my eyes and smearing my makeup. Gum, because one time a boy in my math class said I had bad breath. I’d had a tuna sandwich for lunch. I stopped eating tuna but chewed gum constantly.

The embarrassing things I only realized I needed in a moment of panic. A pad wrapped in pink plastic? I’d fumble it open in a public bathroom as I prayed I hadn’t bled through my shorts again. A tiny stick of deodorant? I couldn’t seem to stop sweating even when I was sitting still. I got the purse for Christmas. I can’t remember what it looked like. I remember how hot my face felt when I’d dig through it looking for another embarrassing thing.

Western culture’s obsession with the purse and female sexuality carried into the 20th century. Surprising absolutely no one, Sigmund Freud insisted a woman’s purse “was a substitute for her genitals” and that a woman rifling through her purse was “representative of masturbation.” In my experience, masturbation is nothing like trying to find a pen in the deep recesses of a purse. But it is not surprising at all that Freud viewed the quest for female pleasure as a frustrated search. Ahem.

In 1997, the year I turned 12, literary quarterly Salmagundi (a favorite of Susan Sontag’s) published “The Contents of Women’s Purses: An Accessory in Crisis,” by Daniel Harris. The essay is so ripe with misogyny I spent an hour trying to figure out if it was a joke. It appears to be in earnest. Even if I’d found a punchline, it’s the kind of joke that’d only get a laugh from people who really, really don’t like women. Daniel Harris argues the purse is a relic of the pre-industrialized repressed woman. His repressed woman lived in a domestic sphere rife with frigid possessiveness. Harris thinks women carry purses so they can keep clutching that dark-aged domestic sphere, while standing blinking and confused in the sun of the public world. Modern industrial society had begun to produce many more things than any one person could ever retain, but women hadn’t got the memo; their purses were the proof.

For Freud, the purse was a woman’s genitals. For Harris, it is her blighted womb. He called the purse

an almost tragic collection of the good intentions of the efficient homemaker who, while she dreams of mending and recycling the avalanche of clutter she carries, simply does not have the time, ingenuity, or will power to carry out the aborted projects and stillborn ideas contained in a bag that, however stylish, frequently amounts to little more than a traveling lost-and-found.

Harris hated purses! He hated women who carry them! So much! He went on,

“The proverbial rat’s nest of the purse, which sometimes looks like the lair of a slovenly nocturnal creature, is also the result of a strong psychological need for mess, which women use as a form of rebellion.” I just want to know how many times he’s asked a friend if she’ll carry his keys in her purse.

Harris declared the homemaker of the past “over-dressed, uptight, priggish,” a “dowdy matriarch in her support hose and sensible shoes, clutching her pocketbook like an anxious hen.” As for the woman in the workplace, he was really disgusted by her, too. He argued that “the pocketbook is the place on her own body where the perfectly manicured office worker makes a kind of mud pie, indulging in an infantile act of liberating self-desecration.” By the end of the essay, Harris concluded women will only be sexually liberated once they’ve abandoned purses. I don’t know where the sexually liberated purse-less women were supposed to keep the condoms purse-less men refuse to carry.

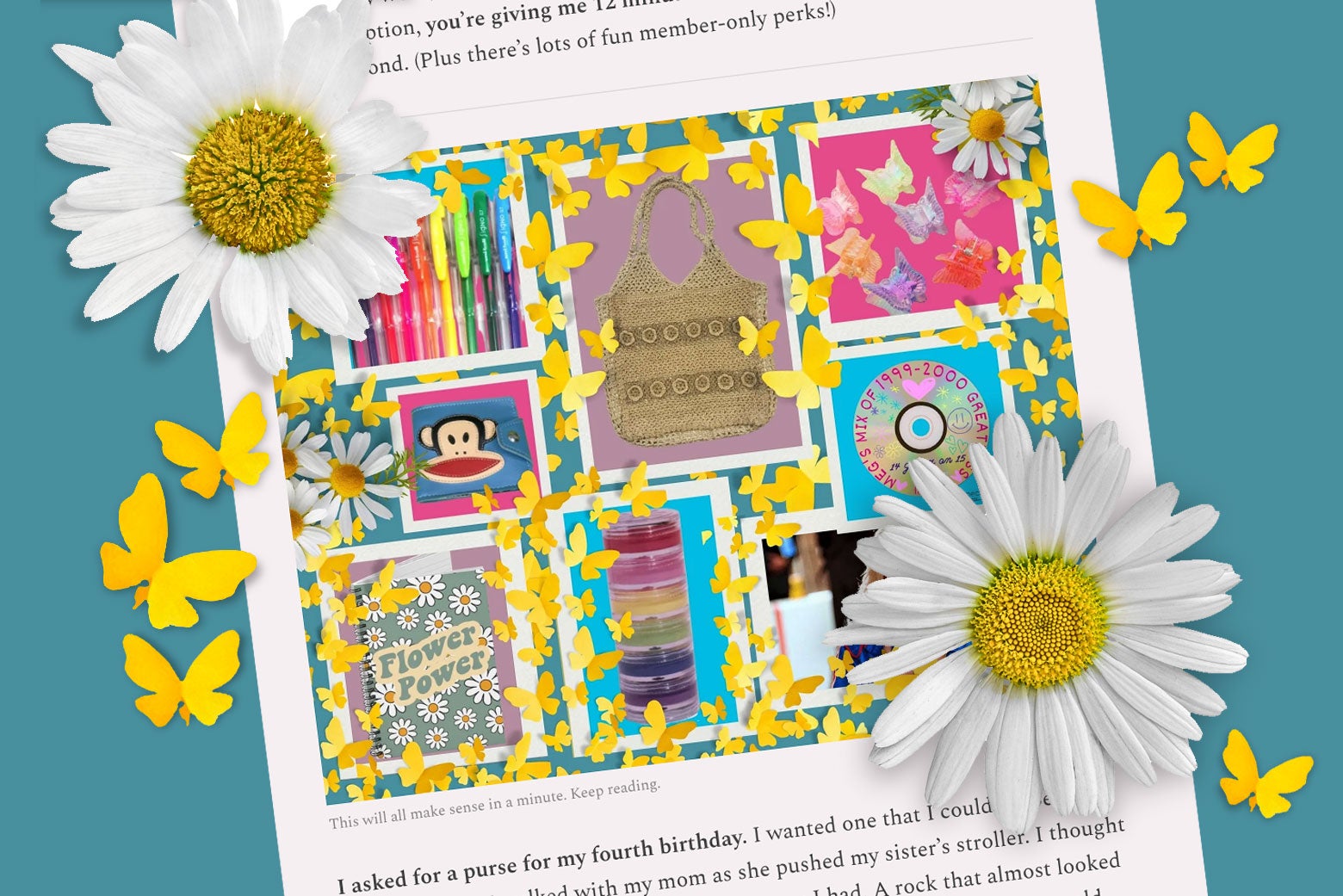

I saved up for a new purse when I was 14. I wanted one that I could drape across my left shoulder when I walked with my best friend around the mall. I was back to thinking purses were for holding treasures. The treasures I had. Rainbow colored gel pens, with ink that slid across paper like frosting. A notebook, for the things I thought but couldn’t say. A stack of rainbow-colored lip glosses, even though I only used the pink and red. The blue Paul Frank wallet my mom got me for Christmas. A CD of songs burned for a friend, or by a friend. A few butterfly clips, because my hair still didn’t lay flat. Knock-off Charlie’s Angels glasses, because I felt like Drew Barrymore when I put them on.

And the treasures I’d find. A note my friend Riley passed me in our LDS church meetinghouse? I could just reach over and take it. A trilobite fossil I found in a creek on a trip to Kentucky? I could just reach down and grab it. I remember what that purse looked like—a straw tote with little straw flowers strung across it.

In 2011, Quentin L. Cook, an apostle in the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, gave a talk praising LDS women for their unpaid care work. In the talk, he told a story the LDS church calls the Parable of the Purse. Cook’s version of the purse is about female sexuality too—the purse as proof of female purity. In this “parable,” a teenage girl leaves her purse at a church dance. Her youth group leaders unpack the purse to try to identify the girl. With each item retrieved from the purse, the leaders assign the girl a virtue. In Cook’s sermon, the contents of the girl’s purse were put on exhibition as “a quiet example of a young lady living the gospel.”

The purse holds a pamphlet of church youth standards, with instructions about chastity and modesty. There is also a notebook with scriptures written inside of it. Both were evidence the owner is a “stalwart young woman.” Next they pull out “breath mints, soap, lotion, and a brush.” She could have had the breath mints because she planned on making out with someone in the parking lot of the church dance. But that’s not how Cook or her leaders interpreted it. Cook said he loved what the leaders said upon finding the toiletries: “Oh, good things come out of her mouth; she has clean and soft hands; and she takes care of herself.”

A homemade coin purse and cash follow, each proving the purse owner was “creative and prepared.” And finally, a recipe for a cake, with a note that she was going to make it for a friend. When they found the recipe, Cook said the leaders in his story “almost screamed, ‘She’s a HOMEMAKER! Thoughtful and service-minded.’ ” Homemaking is the pinnacle of the story because it’s the pinnacle of Cook’s concept of womanhood.

The Parable of the Purse has been told over and over to young LDS girls. Many have been invited to Parable of the Purse activities featuring construction paper purse crafts and purse-shaped tea sandwiches. Their leaders work hard on those crafts and sandwiches. They’ve also been told, in and out of church, that a purse is never just a purse. Is it any surprise that they teach what they’ve been taught? Of course, there is no Parable of the Pocket. Men are rarely reduced to what they carry.

I bought myself a purse this year. I am 37. I wanted one I could pull over my head and across my chest when I walk around my city neighborhood. Now, I think purses are for holding whatever needs carrying. The things I carry now. A wallet, the width of the Strawberry Shortcake sugar skull sticker I stuck on it months ago. My phone, in a case chewed up by our puppy. A receipt my dad signed, the year before he died. The things I’ll need to carry. A crumpled wrapper from the snack my daughter Brontë eats on her way into ballet? I’ll reach out and take it. One of the millions of leaves turned red and yellow in my Denver fall? I can just reach down and pick it up. I could tell you what the purse looks like, but I don’t think I will.