On page 158 of a heavy, leather-bound Paris police register from the 19th century, a handwritten page headed with a photograph details the activities of a young “courtesan” called Sarah Bernhardt.

The Book of Courtesans, as it was known by the then equivalent of the vice squad, was a detailed record of high-class sex workers, often actors and dancers, who were the mistresses of princes, aristocrats and the wealthy.

Bernhardt, then in her teens and noted as being popular with “old men and especially members of parliament” went on to become an icon of France’s belle époque and an international star of stage and, later, silent screen. On her death in 1923, thousands lined the funeral route to Père Lachaise cemetery and extra carriages had to be hired to transport the enormous wreaths.

Now a new exhibition in Paris to mark the centenary of her death aims to show the many faces of the woman nicknamed “La Divine” who became a Hollywood-style celebrity before Hollywood even existed.

“She was the first real star in history; she paved the way for the likes of Greta Garbo, Marilyn Monroe, Madonna and Beyoncé,” said Annick Lemoine, director of the Petit Palais, where the event , described by critics as “exceptional” and “unmissable”, opens on Friday.

“But she was not only a great actress, she was also an influencer of fashion, an artist and a sculptor, a writer and an activist,” said Lemoine. “We aim to show all her many faces. Sarah Bernhardt was a woman whose life still resonates today for the variety of her talent and her free spirit.”

Bernhardt, the daughter of a high-class courtesan whose patrons included the Duke of Morny, the half-brother of Emperor Napoleon III, was educated at an exclusive convent school near Versailles where she announced her intention to become a nun.

Instead, she fell in love with the theatre after her mother, Morny, and the novelist Alexandre Dumas père, author of The Three Musketeers and The Count of Monte Cristo, took her to the Comédie-Française. Under Dumas’s guidance Bernhardt studied acting at the Paris Conservatory making her stage debut in Racine’s Iphigénie, which was not a success.

She was forced to leave the Comédie Française after refusing to apologise for slapping an established actor, and travelled to Belgium. An affair with a Belgian aristocrat led to the birth of her only child, Maurice. She was friends with the writer George Sand, and visited in her dressing room by the likes of Gustave Flaubert and Léon Gambetta.

Bernhardt would later return to the prestigious Comédie Française to perform some of her most celebrated roles before setting up her own company and setting off on a two-year tour of England and the US. In 1899, aged 54, she took the title role in a French adaptation of Hamlet, a performance she reprised in London and Stratford.

She was hot-headed, rebellious and frequently mired in scandal. Her stage style was often melodramatic and self-promoting: as Mark Twain wrote: “There are five kinds of actresses: bad actresses, fair actresses, good actresses, great actresses … and then there is Sarah Bernhardt.” Oscar Wilde called her “the Incomparable One” and wrote the play Salomé – banned by British censors – in French for her. The British author DH Lawrence saw Bernhardt perform La Dame aux Camélias in 1908, and wrote: “Sarah was wonderful and terrible … she is not pretty, her voice is not sweet, but there is the incarnation of wild emotion that we share with all living things.”

As her wealth and fame increased, Bernhardt took on her own Paris theatres, commissioning the Czech artist Alphonse Mucha to produce distinctive art nouveau posters for performances, touring to make money to pay for her extravagant lifestyle.

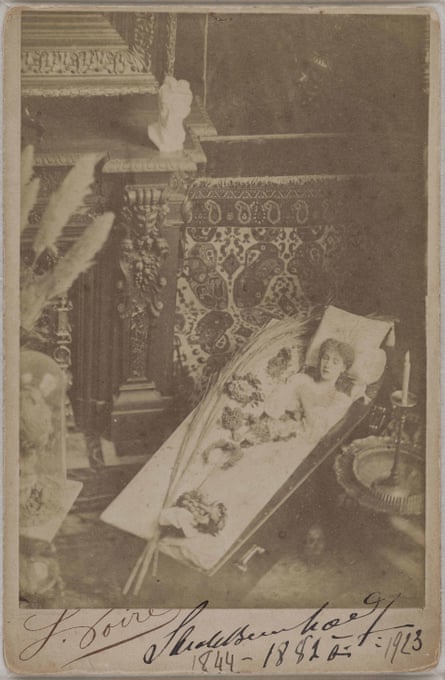

All the while she cultivated a reputation for eccentricity, being photographed sleeping in a coffin and encouraging wild rumours about her behaviour while taking on risky dramatic roles. In 1900, she was one of the first actors to star in a moving picture and later starred as Queen Elizabeth I in a 1912 French film. During the first world war, she entertained troops at Verdun and Argonne despite having had a leg amputated after an injury led to gangrene, and toured the US. She died in 1923 as a result of kidney disease.

The exhibition is at the Petit Palais in Paris until 27 August, and features the Book of Courtesans and 400 other objects, including clothes, jewels, posters, photographs as well as paintings and sculptures created by Bernhardt.