Poor Girls Are Leaving Their Brothers Behind

As a college education becomes increasingly important in today’s economy, it’s girls, not boys, who are succeeding in school. For kids from poor families, that can make the difference between social mobility and a lifetime of poverty.

MERCED, California—Nita Vue’s parents, refugees from Laos, wanted all nine of their children go to college. But Nita, now 20, is the only one of her brothers and sisters who is going to get a degree. A few of her sisters began college, and one nearly completed nursing school, she told me. Her brothers were less interested. “The way I grew up, the girls were more into schooling,” she said. “Women tended to have higher expectations than men did.”

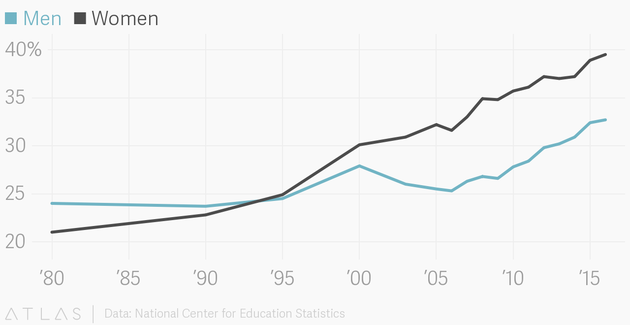

This is not unusual. Across socioeconomic classes, women are increasingly enrolling and completing postsecondary education, while, even as opportunities for people without a college education shrink, men’s rates of graduation remain relatively stagnant. In 2015, the most recent year for which data is available, 72.5 percent of females who had recently graduated high school were enrolled in a two-year or four-year college, compared to 65.8 percent of men. That’s a big difference from 1967, when 57 percent of recent male high-school grads were in college, compared to 47.2 percent of women.

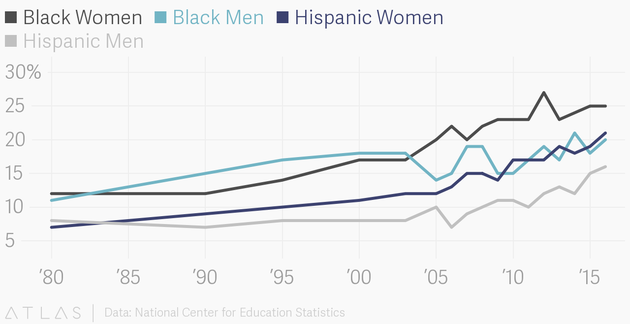

Women from low-income and minority families especially have made great strides in recent decades. Just 12.4 percent of men from low-income families who were high-school sophomores in 2002 had received a bachelor’s degree by 2013, compared to 17.6 percent of women. And in 2016, 22 percent of Hispanic women ages 25 to 29 had a bachelor’s degree, compared to 16 percent of Hispanic men.

(While poor women are outpacing poor men, it is important to note that in the big picture, poor women are nevertheless far behind their richer counterparts. About 70 percent of women from a high socioeconomic status who were high school sophomores in 2002 had gotten bachelor’s degrees by 2013, compared to 17.6 percent of women from low socioeconomic status.)

This gender gap in college completion has been a long time in the making. In the early 1900s, when some elite colleges started opening up to women, women quickly got better grades than men, according to Claudia Buchmann, a professor of sociology at Ohio State and the co-author of The Rise of Women: The Growing Gender Gap in Education and What it Means for American Schools. In the 1970s, as more women started attending college, they started graduating at higher and higher rates, while men’s enrollment and graduation rates remained relatively flat. But until recently, the women attending college were mostly from elite families. Now, women from lower-income families are increasingly attending college.

This is a positive development for women, because a college education is increasingly important in today’s economy. Out of the 11.6 million jobs created after the recession, 8.4 million of those went to those with at least a bachelor’s degree, according to the Center on Education and the Workforce at Georgetown. But while women across socioeconomic classes are embracing the idea that education is important and are pursuing postsecondary degrees, many men from lower-income households are not. “The puzzle is—why don't boys get it? There’s all this talk that we hear constantly, about the benefits of a college degree,” said Buchmann.

Some of the problem is that boys from low-income families appear to struggle more in school than girls do. They lag behind as early as kindergarten even though health tests show that, at the time of birth, they are just as healthy and cognitively able to learn as their sisters, a recent paper found. This is partly because they appear to be more affected by poverty and stress than girls are. “Boys are differentially sensitive to negative environments in general,” one of the paper’s authors, Northwestern professor David Figlio, told me. These findings dovetail with much-cited research out of the Equality of Opportunity Project that finds that childhood disadvantage is especially harmful for boys.

School quality is also more important for boys than for girls, Figlio said, and since many low-income families attend poor-quality schools, their sons, who are already lagging behind their daughters, fall even further behind. The paper found that lower-income boys often do worse in elementary and middle school than their sisters, and have more behavioral problems, which can lead them to disengage with school entirely or get kicked out.

Nita Vue told me she was always set on college, even when she was in grade school. Neither of her parents has a college education, and neither has worked recently, but they encouraged all of their children to focus on school. Nita, who is now a junior at the University of California-Merced, would come home from school and read while her siblings were listening to music. She always had good grades, and graduated from high school with a 4.0 grade point average. In general, her sisters did better academically than her brothers did, her mother, Mai Kao Vue, told me. “The girls were more into schooling, and the boys were more outgoing,” she said.

What is it about girls? The differences start young: Girls enter kindergarten more prepared than boys, and derive more satisfaction from pleasing parents and teachers than boys do, according to Buchmann. In one study, 62 percent of eighth-grade girls said that good grades were “very important,” compared to 50 percent of boys, according to Buchmann and her co-author Thomas DiPrete. Girls also have more of the social and behavioral skills that are important for succeeding in school from an early age, Buchmann said.

Boys often feel pressured to act “masculine,” which can lead them to eschew school —one study showed that boys put a lot of effort into school are often labeled as “gay” or “pussies.” Yet boys who don’t buy into those stereotypes and participate in music, dance, or art, do better than other boys academically in eighth grade, according to Buchmann and DiPrete. Those different levels of engagement can make a difference for college attendance: students who reported getting mostly As in middle school have a 70 percent chance of completing college by age 25, while those who get mostly Cs have only a 10 percent chance.

How parents raise children can exacerbate these dynamics. Pressures to be “masculine” are often stronger in lower-income or working-class families, Buchmann says. “The notion of what it means to be a boy and a man, especially among lower working-class boys, makes it such that they see doing well in school as something that girls and women do, and they don’t want any part of it,” Buchmann told me. This is especially true if boys see male role models like fathers or older family members working physical, blue-collar jobs that don’t require an education. They may assume that they’ll be able to work those jobs too, even if they’re disappearing, and think that doing anything else is too “girly.” By contrast, if boys have role models that are educated, they do better in school. Better-educated parents often teach their children a different concept of masculinity in which academic achievement is important. Moreover, they are more likely to know men in careers that require an education, and to have those men as their role models.

Nita’s brother, Por Vue, who is now 28, told me he thought he was deeply affected by his family’s lack of knowledge about the educational system. He actually applied to and was accepted into Cal State Monterey Bay, but his parents advised him to instead go to a junior college closer to home, he told me. But the junior college was overcrowded and he couldn’t get into many of the classes he wanted, so had to change his major. Then, while he was in college, he started a family, and later dropped out so he could support his wife and kids. He’s now a manager at PetSmart, where he makes around $13 an hour. “I think if I’d had a better family background, I would have had knowledge that other people had, and I would have been able to go further,” he told me.

Boys may also be more susceptible to short-term instant gratification than girls are, Buchmann told me. Boys may have a harder time slogging away at a college degree and paying for it when they know there are jobs available where they could get paid a decent wage, even if that job might not be a long-term proposition. I talked to a 31-year-old in Merced named Edward Vasquez who was one-and-a-half years into a two-year nursing program when he dropped out to take a job as a certified nursing assistant that paid $17.50 an hour. He’s since lost his job and is looking for work.

This is not to say that men can’t succeed if they don’t have a college education. I talked to a woman named Olga Jimenez who was raised by a single mother, and who went to college when her brothers didn’t. But her brother has still made a good career as a real-estate agent, and has a license and his own office, she told me. Meanwhile, Olga had to work three jobs at once while she attended Whittier College and is still paying off her college debt.

Yet Jimenez’s brother is the exception, not the rule. People with just a high-school diploma make, on average, $692 a week, compared to $1,156 for those with a bachelor’s degree. And the returns of a college education have grown over time. People with a bachelor’s degree or higher earn 14 percent more than they did in 1979, on average, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics; people with a high school degree earn 12 percent less.

As the gender gap grows, there are wider implications for society. People are more likely to pair with others who have a similar educational background; as more women get postsecondary degrees than men, women will increasingly find their marriage prospects dimming. This is already happening in some areas of the country—I wrote in May about a town in Ohio where the women complained that all the men were on drugs or unemployed, while the women held down steady jobs. Their daughters will face a similar future, unless they can get their sons to succeed at—and care about—school.