Real Men Drive Electric Trucks

How much will American men have to adapt to help keep the planet from roasting?

“We brought the car to the American people. Then we built them a truck,” a male voice boomed during the launch event for the Ford F-150 Lightning. As the streetlights of Dearborn, Michigan, flickered lazily behind the stage set up outside company headquarters, a giant screen showed black-and-white footage of workers at an early-20th-century Ford assembly plant. Across half an hour of futuristic blue strobes and thunderous sound effects, the American mythos flashed on the screen—cowboys, football players, oil-rig workers. For men like these (and almost all were men, most of them white) this electric truck would be “a hard-working partner with an unbreakable handshake,” a narrator intoned. The Ford F-150 Lightning won’t be available to consumers until next spring, but its reveal was considered such a big deal—by both the auto industry and supporters of renewable energy—that President Joe Biden showed up the day before for a test drive.

U.S. consumers are in the midst of a 40-year-long love affair with pickup trucks, one that began when pickups were marketed to urban and suburban consumers. Five of the top 10 vehicles sold in the United States in 2020 were pickups, which, according to preliminary 2020 data, get almost 40 percent fewer miles driven for each gallon of fuel consumed than smaller cars. Pickups are getting bigger too: The newest Ford F-250 can weigh up to 5,700 pounds (almost 1,400 pounds more than the 1999 model) and towers over most of us mortals, making it a true menace if driven by someone keen on pushing others off the road.

Enter the all-electric pickup. The Lightning is one of several electricity-powered light trucks about to hit the market; by 2023, consumer options will include General Motors’ adaptation of its beefy Hummer and the R1T, a sleek, expensive, vegan-leather-upholstered pickup from the auto-manufacturing start-up Rivian. But the gas-powered F-150 has been the nation’s best-selling pickup for more than four decades, and Ford is betting that the electric version will be similarly dominant—the company even has a prototype for an all-electric, 70s-style model designed to appeal to vintage sensibilities. Three months after the Lightning’s launch, early demand was so high that the automaker doubled its annual production target to 80,000 trucks.

What’s unknown is whether the millions of buyers who have become accustomed to taller, beefier, more polluting trucks—including the farmers, contractors, and oil-rig workers so often represented in Ford ads—will dish out at least $12,000 more for a base model of the climate-friendlier electric version (though many consumers will be able to take advantage of state and federal incentives to bring the price down).

Research by Aaron R. Brough, a professor of marketing and strategy at Utah State University, and James E. B. Wilkie, formerly of the University of Notre Dame, suggests that price may not be the only obstacle to the widespread adoption of electric trucks. In seven experiments involving more than 2,000 participants in the U.S. and China, Brough and Wilkie found that both men and women associated caring for the environment with being more feminine. His research showed that in both countries, men’s consumer choices were shaped by an unconscious bias against femininity and, in turn, against more eco-friendly behaviors. The co-authors found that many men tend to avoid products marketed as environmentally responsible because they “want to feel macho, and they worry that eco-friendly behaviors might brand them as feminine.”

The study is part of a new crop of research on the relationship between gender identities and environmental attitudes. In Sweden, a team of researchers recently estimated that consumption by Swedish men generates 16 percent more emissions than that of Swedish women, even though both groups spend roughly the same amount on services and goods. Men, it turns out, spend more on energy (particularly on gas and diesel for their cars) and eat more meat on average—both of which create more carbon emissions. If this sounds clichéd, know that women also fulfilled cultural stereotypes by spending a greater share of their money on clothing, health services, and home décor.

By reworking the pickup truck, a powerful marker of American male identity, Ford and its competitors are performing a real-world test of how sticky these stereotypes actually are. If climate consciousness can’t be manly, can it coexist with manliness? The Lightning and its siblings will help us find out.

On a muggy morning this summer, I stood outside the Bay Center arena in downtown Pensacola, Florida, waiting to see my very first monster-truck show. A container truck selling merchandise for the Monster Jam tour brand was parked in front, hawking children’s ear-protecting headphones made to look like giant truck wheels. Behind me, a 20-something-year-old mother with blond hair tied neatly into a bun tried to contain the excitement of her two preschoolers.

“I can’t wait to see the trucks flying in the air!” one of the boys told me, digging into his shorts pocket to show me a miniature replica of Grave Digger, one of the monster trucks we were about to see, complete with neon-green flames spread over the hood and a grimacing skull on the side window. Inside the convention center, I lost track of the boys but saw dozens more, some even younger, with similar toys. Men from their 20s to their late 70s wore T-shirts featuring American flags and the most famous of all monster trucks: Bigfoot, the 1974 Ford F-250 pickup outfitted by its owner with a raised bed and 48-inch tires—the giant motorized toy of so many boys’ dreams.

In this crowd, Gustavo Arias’s pressed, button-down shirt stood out. Barely 5 feet tall, Arias has the build of a wrestler, and although his 3-year-old son had persuaded him to attend the show, it hadn’t been a tough sell: Arias drives a Chevy Silverado that he’s raised an extra four inches off the ground. “I switched out the regular tires and got bigger ones,” he told me. “I like tall cars. They make me feel more in control.” In his native Honduras, pickups are popular as dependable workhorses, he said. The American love of trucks has a different dimension: Size matters. Only in the U.S. had he seen the big tires and raised truck beds: “Here, you look around and everyone is doing it.”

Arias and his son were most impressed by Megalodon, the 17-foot-long, 12,000-pound custom pickup painted and shaped like the head of a shark. Its driver, Tristan England of Paris, Texas, told me that his truck of choice was a Ford F-350, but said he was a natural behind any wheel. “I’m not bragging on myself; it’s just what everybody tells me,” he said, smiling as he stood beside his machine.

When England and the other drivers climbed into their respective trucks to rev their engines, I retreated to a seat high in the bleachers. Even there I found myself overwhelmed, nearly nauseated, by the clouds of black smoke and the noise spewed by the six machines. For the next three hours, the big-wheeled monster trucks popped wheelies and executed jumps, pushing dirt around in the pit and accruing points for each flashy display. England, the show favorite, boasted loudly and frequently into a microphone in between tricks, and the crowd clamored for more. At one point, “Macho Man” by the Village People blared from the loudspeakers, and I chuckled as I watched a group of boys seated in front of me pretend to flex their arm muscles to the beat—until they realized they were featured on the convention center’s jumbotron.

The show ended with Megalodon as the victor. But the real winner was the conglomerate behind Monster Jam, which has turned free DIY entertainment like tractor-pulling contests into a show that can cost upwards of $100 or more per family. Monster Jam, a “360° lifestyle brand company,” is operated by Feld Entertainment, whose CEO, Kenneth Feld, has a net worth of about $2 billion. Feld told the Associated Press in 2014, “We are monster-trucking the world.”

What if the monster-truck world were electrified? Perhaps it was a failure of my own imagination, but from my vantage point at the top of the bleachers, I couldn’t picture the crowd cheering for EV vehicles, no matter how large or souped up. The mass arousal seemed to be triggered by the smell of diesel and the noise of revving engines. Those sounds, smells, and sights, as commodified by the Monster Jam franchise, evoke the peculiarly American ideal of rural life: self-sufficiency sustained by unbridled male power. The monster-truck show is a staged fantasy, in which men are allowed to show love—if only for machines.

The next morning, I jumped in my economy class, gas-powered Nissan Versa and headed toward a bluff overlooking Pensacola Bay. I wanted to visit Fort Barrancas, a massive, austere brick structure built on a site first fortified by the Spanish in 1698 and now part of Naval Air Station Pensacola. Famous for its four-foot-thick walls, the fort has witnessed centuries of male power contests: It was completely destroyed by the French in 1719, rebuilt and occupied by the British in 1763, then recaptured by the Spanish in 1781.

As I approached the gate, I ended up behind a large GMC pickup with one of those exhaust attachments that make a beastly noise every time the driver steps on the gas. When we finally reached the entrance to Fort Barrancas, the pickup was waved inside, but I was told that, since a shooting incident in 2019, the site was open only to U.S. military personnel, though its website still lists regular hours. “Sorry, ma’am,” said the uniform-clad man at the gate, pointing to where I needed to turn around.

Earlier this year, the Pentagon officially began incorporating climate analysis into its National Defense Strategy. “There is little about what the department does to defend the American people that is not affected by climate change,” Defense Secretary Lloyd Austin has said. “It is a national-security issue, and we must treat it as such.” As a threat, it doesn’t evoke the same visceral response as a foreign invasion, but the danger is similarly acute. According to sea-level-rise projections for the bay, the fort, which now stands just 26 feet above sea level, could be threatened by flooding by the end of the century.

As the military’s leaders turn their attention to climate change, they are doing so in a culture that is still intensely and stereotypically macho. At its silliest, this can manifest in incidents like one in 2018, in which two Marine Corps aviators from Southern California flew their T-34C Turbo Mentor in a phallic-shaped pattern over the Salton Sea, about 140 miles southeast of Los Angeles. On a more serious level, it can interfere with the military’s ability to reduce its own carbon footprint—which is larger than that of most countries—by celebrating air shows and other gas-guzzling exhibitions of force. To move away from fossil fuels will mean moving past such habitual ways of thinking and acting—whether that means better establishing a link between classic notions of manliness and environmentalism, or rethinking those notions entirely.

Traci Brynne Voyles, an associate professor of gender studies at the University of Oklahoma who has written about the Salton Sea incident, argues that while societies have always shaped the environment around them to fit their needs, it’s more and more necessary to look at the ways in which gender influences—and restricts—human relationships with the environment. In order to confront the climate crisis, Voyles says, we’ll also need to confront our assumptions about masculinity and femininity.

Twenty years ago, Martin Hultman had the kind of gender-identity transformation that Voyles sees as necessary to human survival. Hultman, who teaches at Chalmers University of Technology in Gothenburg, Sweden, told me that he was what he now calls an “industrial breadwinner” male, flying all over the world and regularly eating meat. “I didn’t really question things in the sense of [denying] climate change, but I wasn’t looking for that knowledge either,” he said. “So I was just kind of living a wealthy Western life, so to speak.”

Hultman was starting his Ph.D. in technology and social change when, like Voyles, he became interested in the intersection between gender and human relationships with the environment in Europe and the U.S. He watched with fascination as Arnold Schwarzenegger, an action-movie star and poster boy for white virility, entered politics and became the governor of California. Little by little, Hultman said, Schwarzenegger seemed to be questioning his past self.

As governor, Schwarzenegger supported the expansion of renewable energy and formed multilateral coalitions with other states and countries. After leaving public office, he moved even further toward what Hultman and his fellow researcher Paul Pulé call “ecological masculinities,” publicly expressing support for the youth climate movement in its fight against oil giants such as ExxonMobil and Chevron. After the #MeToo movement exploded on social media, Schwarzenegger pivoted yet again, acknowledging that he had behaved badly toward women in the past. Schwarzenegger’s trajectory from industrial breadwinner in the 1980s to an eco-modern male by the beginning of the 21st century should give us hope, said Hultman. “I think that if such a transformation could happen to him, it might happen to some other American men out there as well,” he told me earnestly.

For the past four years, Hultman has worked with a feminist men’s organization based in Sweden to develop a leadership program called Men in the Climate Crisis. Meeting weekly, two hours at a time, over two months, participants first learn and discuss how men have affected the climate and ecosystems throughout history. After each session, they are given “homework” activities such as eating vegan food, riding a bicycle to work one day, cooking for the family, and planting a tree—simple actions that the participants, like the men in Brough and Wilkie’s marketing study, might previously have dismissed as too feminine. Throughout the course, participants are encouraged to share personal anecdotes and feelings with one another, and they often express grief and anger. “It’s not that easy,” Hultman said. But he too has made the difficult transition: No longer the jet-setter, he now travels by bike and rideshare, and has stopped eating meat.

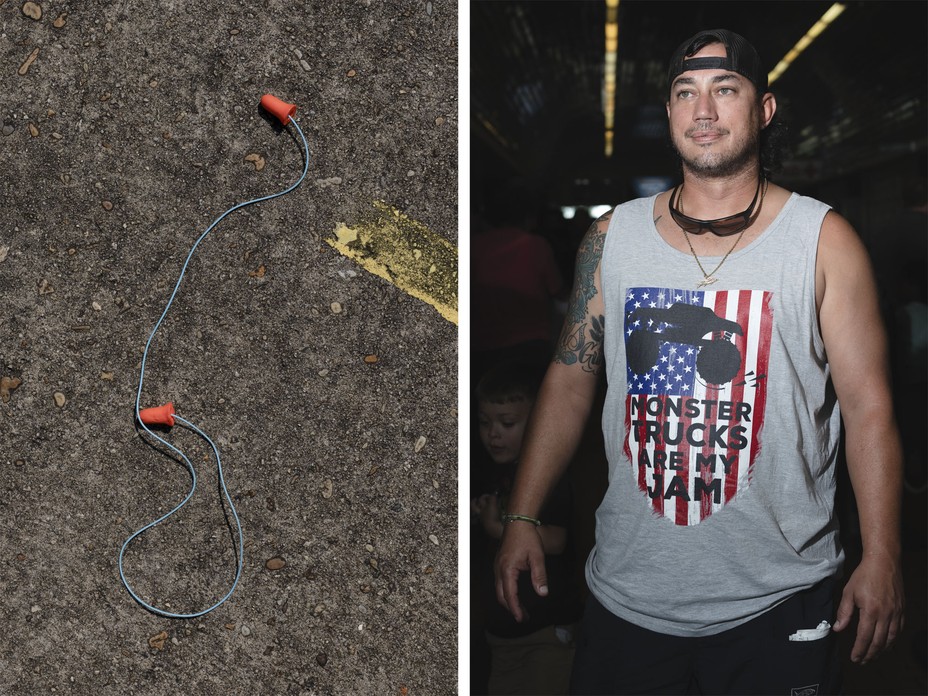

I spoke with Hultman the day before I left for the monster-truck show in Pensacola, and the prospect of encountering ecological masculinities among the crowd felt like a very distant possibility. But during one of the breaks, near the concession stand, I met a man named David Torres. Something in his body language—his wide-open eyes and welcoming smile—made me think he’d be willing to engage with me on this topic. He wore a muscle shirt that read Monster trucks are my jam, and his curly brown hair was shorter on top and longer in the back, like the mullets that were popular when Bigfoot first entered popular culture in 1979. He told me he owned a shop called Top Gun Performance Muffler, about an hour’s drive from Pensacola.

“I think every young boy has a dream, when they see these big old trucks, to get in one and drive them,” he told me. Growing up on a farm in Florida, he loved driving the pickup his family used for chores, because he could feel the roar of its engine in his chest. Now he gets the same feeling at monster-truck shows.

Wary of presenting Torres as a caricature, I asked what he made of the prevailing stereotypes about American guys like him who love big, noisy trucks. It’s not as though men beat their chest while they burn diesel fuel to power work machines, Torres told me. Conceivably, if monster trucks didn’t run on diesel and offered the same emotional release without the pollution, he’d enjoy the show just as well. Torres said he wished electric vehicle batteries could be produced without damage to the environment caused by “tearing up the ground to get the lithium.”

Vehicles of all kinds are going electric, including pickups, city buses, and farm equipment. And someday monster trucks could get there too. “Monster Jam is constantly evolving and has a dedicated research and design department focused on innovation and the growth of the sport,” one of their spokespeople told me when I asked about the possibility.

Torres does have a certain nostalgia for old-school, fuel-powered work vehicles. He grew up working on diesel and gas machines, but his know-how doesn’t extend to electric vehicles, which are controlled by computers and require specialized training and equipment to repair. He expects that as the electric-vehicle market expands, his muffler business will shrink.

In the meantime, Torres is raising his young son to share his love for trucks—“He spends his time on his knees, driving around the living room with his little miniature monster trucks,” he jokes—while also teaching him about climate change and what can be done to slow it. Torres doesn’t speak the emotional language of eco-consciousness, but he seems to have found his own version of ecological masculinity. “You either adapt or you become a fossil,” he told me, concession beer in hand. “The world’s ever changing, and in a good way, right?”

This Atlantic Planet story was supported by the HHMI Department of Science Education.