With regressive gender politics and a restrictive legal system, the Victorian era is not exactly remembered as an empowering era for women. But the Museum of the City of New York is shining a light on a set of oft-forgotten figures: the 19th-century heroines who broke all the rules in a new exhibition called Rebel Women, a tribute to the “nasty women” of the era.

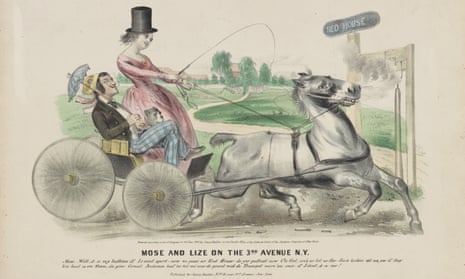

It’s an intimate collection with more than 40 objects on view, including old photographs, fashion garb, posters and poems illustrating the lives of New York’s female activists who fought for equal pay, abortions, divorce and “free love”.

“When people think of 19th-century women, they have a domestic woman in their mind wearing a corset, but there was this whole other side to New York women at the time that was far more rebellious,” said the curator, Marcela Micucci. “Some women were seen as too masculine, political, outspoken and got in trouble for challenging standard gender norms.”

The exhibition includes the likes of Elizabeth Jennings Graham, an African American New Yorker who refused to get off a segregated trolley in 1854 and Hetty Green, a wealthy businesswoman and broker branded “the witch of Wall Street”.

It also features Victoria Claflin Woodhull, who was the first woman to run for president in 1872 (though some debate the legality of her run), and was an advocate for divorce in a time when women were ostracized for it.

“She was a sexual radical,” said Micucci. “Her personal ideologies were outside the traditional gender norms of the time, as women were expected to have kids with one person. Her belief in ‘free love’ didn’t live within that doctrine.”

The exhibition is like a Hollywood walk of fame for 19th-century feminists, but there are no stars on a sidewalk. Rather, there are objects that trace their fiery spirits, including one political cartoon of Woodhull, which appeared in Harper’s Weekly, a magazine which ran in New York from 1857 to 1916, where she was called “Mrs Satan”.

“It captures her rebelliousness, both her free love advocacy and her political activism,” said Micucci.

Relics of Victorian beauty are also on view in the exhibition, including parasols, the heavy, ornate umbrellas (often made of ivory and silk), which women were obliged to carry to protect themselves from the sun, as well as corsets and leather gloves. “We wanted to show the physical restrictions of the Victorian woman who was expected to look very dainty at all times,” said Micucci.

In a time when a “true” Victorian lady only wore pastels and a pale palette of clothing, the pair of red satin boots from the 1870s on view is representative of a rebel woman’s nonconformist spirit.

“Only rebellious women wore scarlet-colored shoes during the day in New York in the 19th century,” Micucci says. “Wearing any form of ‘fancy dress’ on the street during the day was bold, so these shoes are symbolic of the women you see in this exhibition.”

Not every woman subscribed to norms, and there are some working-class women in the show, including those who struggled for equal pay and labor rights. The exhibition gives mention to New York City’s first all-female labor strike, the 1832 Tailoresses Strike, which was led by the tailor Sarah Monroe, who asked: “If it is unfashionable for the men to bear oppression in silence, why should it not also become unfashionable with the women?”

Also on display is the poetry of Adah Isaacs Menken, who was the highest-earning female actor of her time, known for catching the eye of Charles Dickens. Menken, who was an outspoken advocate for equal rights, always dreamed of being recognized as a writer – she published 20 essays and 100 poems, often expressing her opinions on marriage, before her death in 1868. “She was a spitfire in her own right,” said Micucci. “Her poetry was published after her death, we have a handwritten poem by her.”

While not all of the women in the exhibition are from New York City, the exhibition focuses on the activism or work that the women did in the city, which was not always a progressive place.

“New York City in the 19th century was a time of social, economic and cultural change, the rise of the middle class, but women were told to stay at home,” said Micucci. “That’s where we see rebel women stepping out as activists or politicians, or new professional careers in law and medicine that was previously blocked off to them; it was an exciting time.”

The exhibition traces the lives of Dr Susan Smith McKinney-Steward, the first female African American doctor licensed in New York, and Elizabeth Jane Cochrane, an investigative reporter known as “Nellie Bly” who made a record-breaking trip around the world in 72 days.

Another section of the exhibition features women who operated in the criminal underworld. Sophie Lyons was a pickpocket who used her charm to steal from wealthy men, while Ann Trow Lohman, a women’s doctor who ran an office on Fifth Avenue, provided birth control pills and abortions for women despite opposition from secret investigators and the conservative press.

One of the first transgender women ever recorded in history, Mary Jones, is also featured in the exhibition. Born as Peter Sewally, who asserted the right to wear feminine clothing, Jones worked at a brothel on Greene Street when it was a prostitution district, but was arrested in the 1830s for pickpocketing a man. She caused outrage when she appeared in court dressed as a woman.

“It was a gasp moment from the courtroom, as they were expecting a man to show up,” said Micucci. “The media lampooned her and she was found guilty, calling her ‘the man monster’, but she was beautiful, wearing a white dress and looking very elegant, and yet they characterized her as a monster.”

But are these women the unsung heroes of feminism? “I wouldn’t say they’re unsung,” said Micucci. “All of these women have made incredible contributions to women’s history, whether they’re well-known or lesser known.”

“It certainly taps into the ‘nasty women’ and #MeToo women’s rights movement that’s going on right now,” she adds. “We show how history repeats itself and it’s important to trace the early activism of women’s rights.”

- Rebel Women is on display at the Museum of the City of New York until 6 January