A century ago today, the 19th amendment of the US Constitution was ratified. It states that “the right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any State on account of sex.”

Voting is a most indispensable condition of democracy, and one that sits at the core of America’s centuries-long quest for a “more perfect Union.” The process of reaffirming voting as every US adult’s right has been one of naming the obstacles to its exercise, and stating that they should not exist. It is uncovering and eliminating previously unaddressed foils to a core entitlement.

“Everyone” had the right to vote from day one, but it took time for the law to spell out that this meant women, too. And former slaves. And poor people. And—once again, louder, for the racists in the back—Black people. This progression towards the fulfillment of the democratic ideal is far from done: Felon disenfranchisement, and other attempts at voter suppression, still stand in the way of rights that exist but are not being recognized.

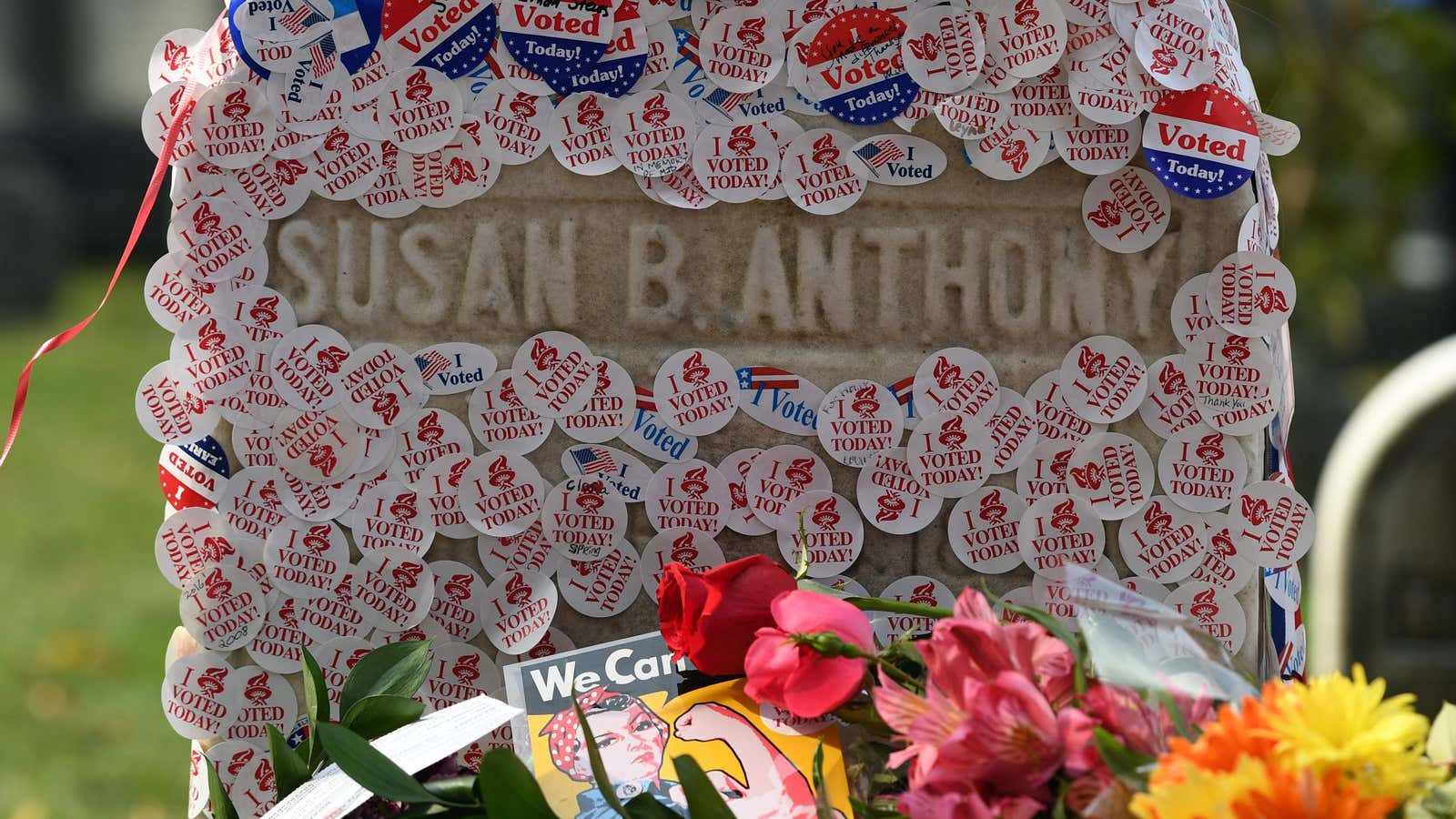

The 19th amendment didn’t make female suffrage legal—it made all the previous instances when it had been denied a crime. And that’s why US president Donald Trump’s intention to posthumously pardon women’s rights activist Susan B. Anthony, who was incarcerated for voting while female, is misguided. It does a disservice to the activist, and to the many others who fought so that women could have representation—as Black suffragist Mary Church Terrell put it, to lift as they climbed.

What Anthony did was a deliberately rebellious act, one that she and her sisters in arms stood by and refused to pay a fine for, knowing it would get them arrested. These were women ready to lose their individual, immediate freedom in the interest of a greater, collective one.

The history of America—the history of all civilization, really—is one of progressively filling the gap between what is legal and what is just. It is an ongoing process, and its advancement rests on a moral behavior that Martin Luther King famously distilled in his Letter from Birmingham Jail: “One has not only a legal but a moral responsibility to obey just laws. Conversely, one has a moral responsibility to disobey unjust laws.”

To pardon Anthony is to forgive her of a crime that should never have been one, to imply that the state has moral standing over her—when it was Anthony’s actions, like many other disobediences before and since, that gave the state its own moral standing. In Anthony’s own words, spoken during her trial, her crime “earnestly and persistently [continues] to urge all women to the practical recognition of the old revolutionary maxim, that ‘Resistance to tyranny is obedience to God.'”

The temptation to erase an unjust crime is understandable. But Anthony’s sentence, like John Lewis’s for each act of good trouble, or Martin Luther King Jr.’s for protesting in Selma, or Sojourner Truth’s for daring to be Black in Indiana, are a point of pride in their biographies, a testament to great ideals and greater courage. They are at once the mark of their heroism and an indelible reminder that the law can be unjust, that indeed it was, and challenging it was—and still is—a profoundly moral act of democracy.