Nearly 70 years before the woman who would become the first known Native American female engineer was born, her great-great-grandfather, John Ross, was fighting for the rights of the Cherokee Nation. In an 1836 letter to U.S. legislators, Ross, the nation’s principal chief, wrote, “Spare our people! Spare the wreck of our prosperity! Let not our deserted homes become the monuments of our desolation!” He was protesting the legitimacy of the Treaty of New Echota, an accord that, without any agreement from Ross or the Cherokee National Council, was used as legal basis to forcibly, fraudulently, and violently expel the remaining Cherokee population from their ancestral homelands.

His protests would ultimately be in vain. Ross and his people would be forced to embark on the Trail of Tears, where his wife, Quatie, would die. Eventually, he and others settled in Park Hill, Oklahoma, a hamlet some five miles south of Tahlequah, the city resting at the southwestern edge of the Ozark Mountains that would come to be the Cherokee Nation’s capital.

It’s an incredible origin story that set the gears in motion for the glass-ceiling-breaking life of Mary Golda Ross, the chief’s great-great-granddaughter. While Chief Ross had fought to keep his people out of obscurity, Mary became a trailblazer by setting her sights on the stars.

“She was the kind of person who would walk through a door and stick in her foot to make sure that it stayed open for others,” says historian Emily A. Margolis, a curator of American women’s history at the National Air and Space Museum and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory. “Not only did she do all these amazing things in aerospace, but she did it at the same time that she was trying to make engineering in general more inclusive and welcoming to all.”

She was born in Park Hill on August 9, 1908, one year after Oklahoma became a state, the second of five children to William Wallace and Mary Henrietta Moore Ross. From a young age, Ross showed promise. She was sent to live with her grandparents to study in Tahlequah and graduated high school at just 16. As a freshman at Northeastern State Teachers College (now Northeastern State University), Ross majored in mathematics, an unusual pick at a time when women were not a necessarily welcome presence in STEM.

But to Ross, math seemed the most obvious and appealing option. “Math was more fun than anything else,” she explained in a 2002 interview with writer Laurel M. Sheppard for Native Peoples magazine. “It was always a game to me.” She often found herself the only woman in her classes, with her male classmates physically insulating themselves from her. “I sat on one side of the room and the guys on the other side of the room,” she recalled to Sheppard. “I guess they didn’t want to associate with me. But I could hold my own with them, and sometimes did better.” She graduated with her bachelor’s in 1928.

In the years after, Ross worked as a high school teacher, a statistical clerk at the Bureau of Indian Affairs, and an adviser to students at a boarding school for Native American students in Santa Fe, New Mexico. During the summers, she took astronomy classes at Colorado State Teachers College, eventually earning her master’s degree in 1938—a feat rarely accomplished by women at the time. (Only 86 women earned Ph.D.’s in mathematics between 1940 and 1949.)

Then came World War II.

Though women have long labored (with little to no recognition) in or outside the home, the war brought an unprecedented jump in female participation in traditionally male professions. Women were called to join the ranks of the production line as their husbands, brothers, and fathers were drafted into the war. Jobs that were previously kept from them were suddenly available, and by 1945, nearly one out of every four married women worked outside the household.

Following the advice of her father, who encouraged her to channel her mathematical pursuits into the war effort, Ross went west. In California, she was hired as an engineer at Lockheed Aircraft Corporation, an aerospace manufacturer that became a key military facility during the war. By the time she joined the company, Ross became one of nearly 480,000 women who worked in the aircraft industry in the United States. Certain aircraft factories located in Southern California, where Lockheed was headquartered, saw 60 percent of their workforce composed of women.

At Lockheed, Ross worked on design issues concerning the P-38 Lightning, which at a whopping 400 mph was one of the fastest fighter jets in the world. Though she put her expertise to use on matters of aeroelasticity and high-speed flight, what truly captured her imagination was a concept that was then inconceivable: space travel. She recalled later, “If I had mentioned it in 1942, my credibility would have been questioned.”

When the war ended in 1945, women often saw themselves pushed out of the workforce as men reentered the labor pool. But lucky for Ross, her genius hadn’t gone unnoticed during her time at Lockheed. Instead, the company sent her to the University of California, Los Angeles to receive her engineering certification. She returned to become one of 40 founding engineers at Skunk Works, the highly secretive Advanced Development Program at Lockheed. She was Skunk Works’ only woman engineer.

“Often at night there were four of us working until 11 p.m.,” she later said in a 1994 interview with San Jose Mercury News. “I was the pencil pusher, doing a lot of research. My state-of-the-art tools were a slide rule and a Frieden computer.”

Much of their work still remains classified today, but what we do know is that Ross got her chance to develop technology for space exploration—no longer a shot-in-the-dark concept. The San Jose Mercury News noted that she worked on “preliminary design concepts for interplanetary space travel, manned and unmanned earth-orbiting flights, [and] the earliest studies of orbiting satellites for both defense and civilian purposes.” Her efforts also helped develop the Agena spacecraft for the Gemini and Apollo programs, which allowed NASA to test equipment for Earth-orbiting and lunar missions. In 1966, she became one of the primary authors of NASA’s Planetary Flight Handbook Vol. III, which touched on the possibility of traveling to Mars and Venus.

“The true extent [of her influence] is unknown, because much of the work that she did remains classified,” Margolis says. “But I think that aerospace technology and knowledge that we have today builds on what came before, and so she is part of the larger trajectory of what aerospace looks like today and will look like in the future.”

By the time Ross retired in 1973, she was involved with the American Indian Science and Engineering Society, as well as the Society of Women Engineers, the conduits through which she worked to recruit and encourage Native American youth to pursue STEM.

Cara Cowan Watts, an engineer from the Cherokee Nation and the CEO of Tulsa Pier Drilling, a Native American–owned and operated drilling business in Oklahoma, remembers her friend’s career as a groundbreaking guide to other Cherokee women in the field. “Mary’s work professionally and later as a community leader inspired me to continue my work in STEM,” says Cowan Watts, who first met Ross in 2004. “Mary was clear in her conversations and her daily actions that you own your career. Achieving excellence in STEM enables you to do incredible things for your nation, your family, and your community. It opens doors for you.”

Still, since Ross’s time, scientific and mathematical fields haven’t seen a significant increase in terms of Native representation. In 2015, for instance, the U.S. engineering workforce was composed of just 0.3 percent Native people and 0.07 percent of Native women.

“The workforce has grown immensely since the time that Mary Golda Ross became the first known Native American woman engineer,” Margolis says. “But we haven’t necessarily seen a corollary increase in the Native representation in those fields.”

Why isn’t Ross as well-known as other space pioneers who loom large in pop culture today? “There is this problem that historians deal with called erasure,” Margolis explains. “When you’re doing the history of women or other people who’ve been marginalized, their labor at the time that they were working was often devalued and invisibilized in a way that meant that it was rare for their contributions and their records that they created to be recorded in archives.”

In Ross’s case, there is an extra level of archival difficulty since so much of her work is still confidential. What we do know of the engineer, though, is in large part thanks to her family. “We only know about her today, because people in the past decided that a story was important and worth saving,” Margolis says. “It’s really a credit to her family and to the archivists and museum professionals that we’re even able to know about what she did.”

Cowan Watts adds, “[Her] impact on my life was to create more of us. … She would be happy to know that she inspired just a few more folks to become engineers or pursue applied math to further our nation.”

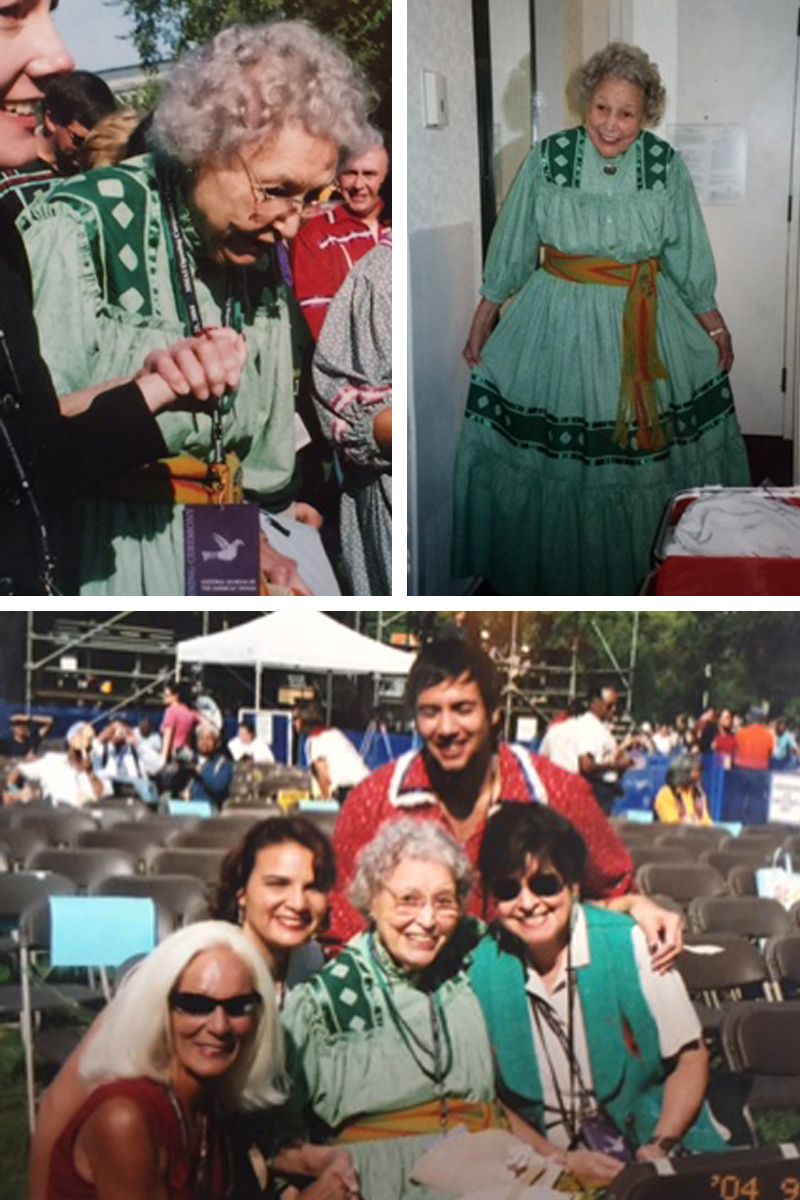

Before she passed on April 29, 2008—just months shy of her 100th birthday—Ross asked her niece to create a traditional Cherokee dress that she could wear to the 2004 opening of the Smithsonian National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C. (which she would eventually leave a $400,000 endowment upon her death). There, on opening day, walking in her green calico dress in a procession alongside thousands of other Native Americans, the history-making pioneer would again pave the way for a brighter future where the contributions of Indigenous people won’t be lost to the dark. As she told a local paper in 2004, “The museum will tell the true story of the Indian—not just the story of the past, but an ongoing story.”

A new statue built in Ross's honor will be erected at the First Americans Museum in Oklahoma City, the capital of her birth state. The statue will be on view starting February 23rd.