In 1962, Mexican artist Mónica Mayer had her first experience with sexual assault: she was an eight-year-old girl walking through a Mexican town with her mother a few steps ahead of her. As Mayer was reading a comic book, a man in his 30s approached.

“He touched my ‘pussy’, as your president would say,” said Mayer over the phone from her studio in Mexico City. “I was shocked but I am even more shocked this is a common experience.”

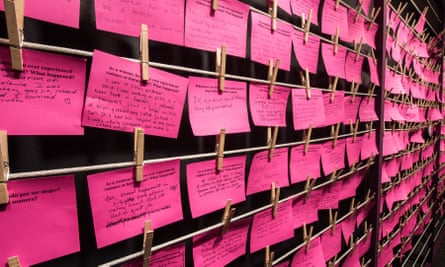

Last week, Mayer installed El Tendedero/The Clothesline Project, an exhibition at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington. A room is filled with a clothesline, pink pieces of paper and pens. Visitors are invited to leave anonymous comments about sexual abuse and harassment.

The pink slips of paper ask: “Have you ever experienced violence or harassment? What happened?” while another reads: “As a woman, where do you feel safe?”

“They don’t have to write anything but their experience,” said Mayer. “As an art piece, it’s more symbolic, it’s not a sociological survey.”

The project initially began in 1978 in Mexico City when Mayer was commissioned to make an artwork that responded to what she disliked most about the city, “which was harassment on public transport”, she said, and it grew from there.

A feminist art pioneer of the 1970s, Mayer co-founded Mexico’s first-ever feminist art collective, Polvo de Gallina Negra (Black Hen Powder) and was included in the 2007 feminist art survey “WACK: Art and the Feminist Revolution” at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles.

Despite her trailblazing participatory artwork from the 1970s, not much has changed over the past 40 years. “Out of 12 women murdered daily in South America, seven are in Mexico,” said Mayer. “We are not going forward, we are going backwards and it’s becoming more violent.”

With the recent sexual assault allegations against Hollywood film producer Harvey Weinstein, Artforum magazine’s former publisher Knight Landesman, as well as cases against comedian Louis CK and actor Kevin Spacey, Mayer isn’t surprised about what’s going on in the entertainment industry.

“There is always something happening in relation to harassment, we’re now talking about it very publicly,” she says. “This clothesline project seemed like it was planned but it’s a coincidence.”

Despite last month’s viral #MeToo Alyssa Milano-led hashtag campaign against sexual violence, Mayer wants the online activism to continue over into the legal system. “It worries me that if allegations become scandals in the media, it doesn’t talk to the legal system where there is a clear punishment,” she said. “We need to have the appropriate punishment.”

This Washington installation has two new questions she hadn’t focused on before; one is: “How do you recover your joy after going through an experience of violence?” The other says: “What have you done or what could you do to stop violence against women?”

“Now in Hollywood and the art world, women in powerful positions are talking about it but most women are not in that position,” said Mayer.

“Some don’t realize how many women are not able to have a voice or denounce harassment or rape, like undocumented women who are in no way going to denounce anything if they have a fear of being deported.”

According to a survey from the National Coalition for Immigrant Women’s Rights, there are 4.1million undocumented women in America. Also, 4 million American citizens live in a household with at least one undocumented parent. “It’s a tense situation,” she said. “We have to make alliances among the women in the arts so these realities are seen.”

Even though this artwork has traveled extensively through Latin America, it strikes a chord with the amount of violence in the US.

“We tend to think Mexico has a lot of harassment but whenever I do this project in the States, it’s just as bad,” said Mayer. “I’m shocked about the level of violence.”

The goal of this artwork is not only to raise awareness of the problems of harassment against women but to arrive at conclusions to help solve the problem.

“The only way we are going to finish with harassment is a really deep cultural change that goes from men re-educating themselves and women re-educating ourselves, the moment we know more about harassment, we can change it,” she said. “It’s something we have to criminalize, a change in society as a whole.”

It ties into her own experience with visiting the US as a Mexican woman – she traveled to Los Angeles to participate in a group exhibition opening at the Hammer Museum this September, Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985. Mayer prepared herself to get across the border with extra papers.

“When I cross the border to exhibit, I ask museums to give me letters so I have a paper proving why I am going – they also send me the numbers of lawyers in case I get into trouble,” she said. “This does not feel friendly, especially when Trump is saying he is going to put up a wall between Mexico and America. It’s the first time in my life I don’t want to go to the United States.”

Despite the fact that she sees things getting worse before they get better, Mayer is optimistic about the future.

“The people who are aware, conscious and participating in activism is what gives me hope,” she said. “There is this fear looming but please try to end this story in a positive way.”

El Tendedero/The Clothesline Project runs until 5 January at the National Museum of Women in the Arts in Washington DC. and the Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960-1985 runs until 31 December at the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles.