As a teenager, Kaoru Akagawa couldn’t read her Japanese grandmother’s letters, but she put it down to her unclear handwriting.

Over a decade later, Kaoru realized her grandmother hadn’t been a poor calligrapher. She had been one of the last generation to use a vanishing script shaped predominantly by and for women.

Legend has it that kana script, which translates to “woman’s hand,” was invented in the ninth century by Kukai, a priest and Sanskrit scholar, although some historians say it’s hard to tell who exactly founded it and where, according to Akagawa.

What is apparent is that the kana characters – which form the basis of kana shodo – represent the different sounds that make up the Japanese language. It was shaped mainly by noble women, although both genders used it to write everything from assassination commands and love letters to poetry and diary entries.

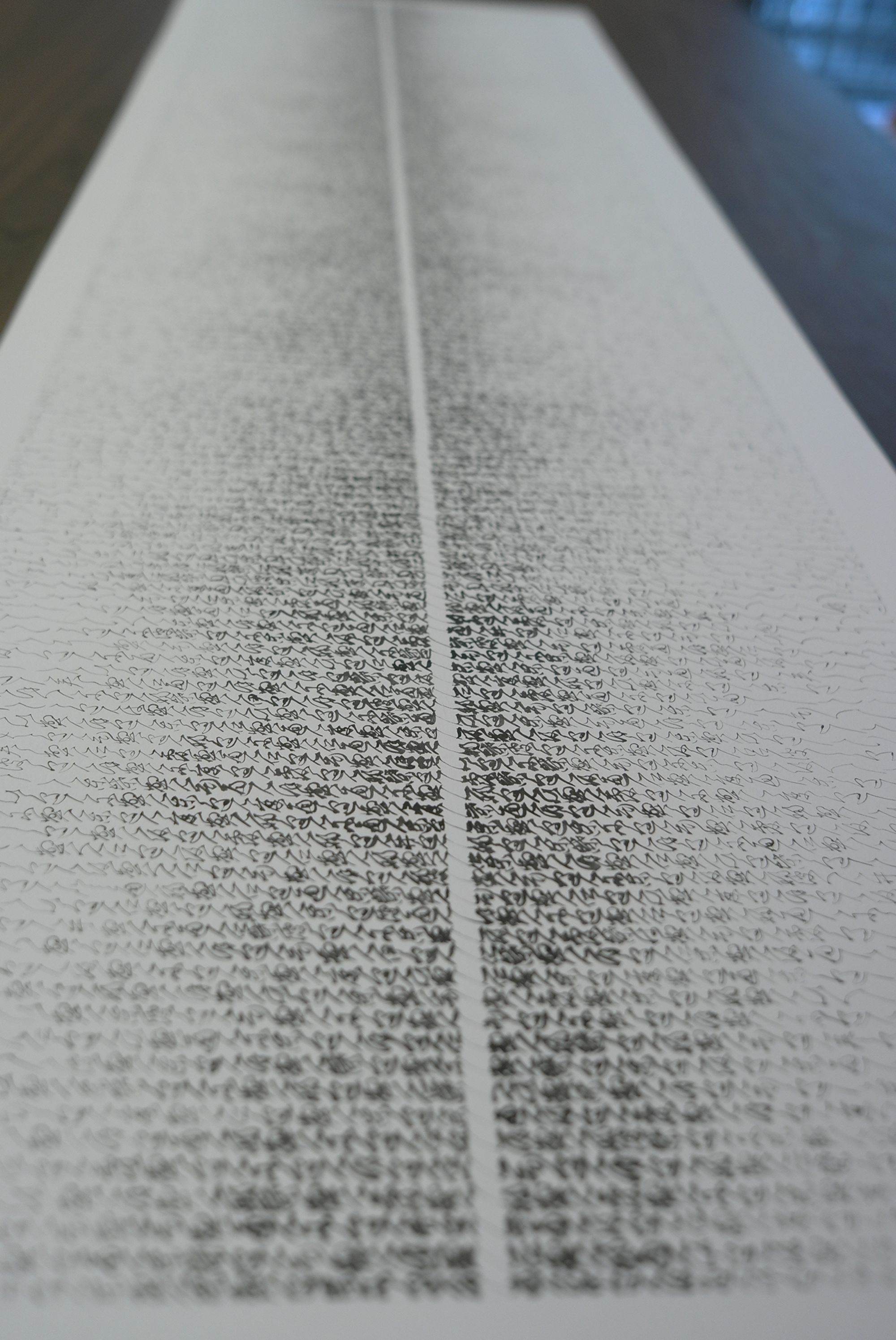

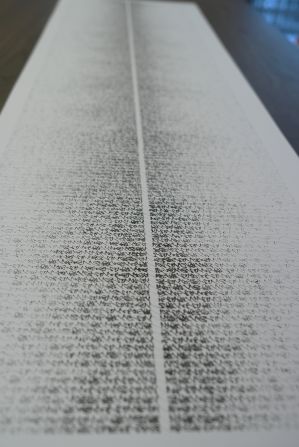

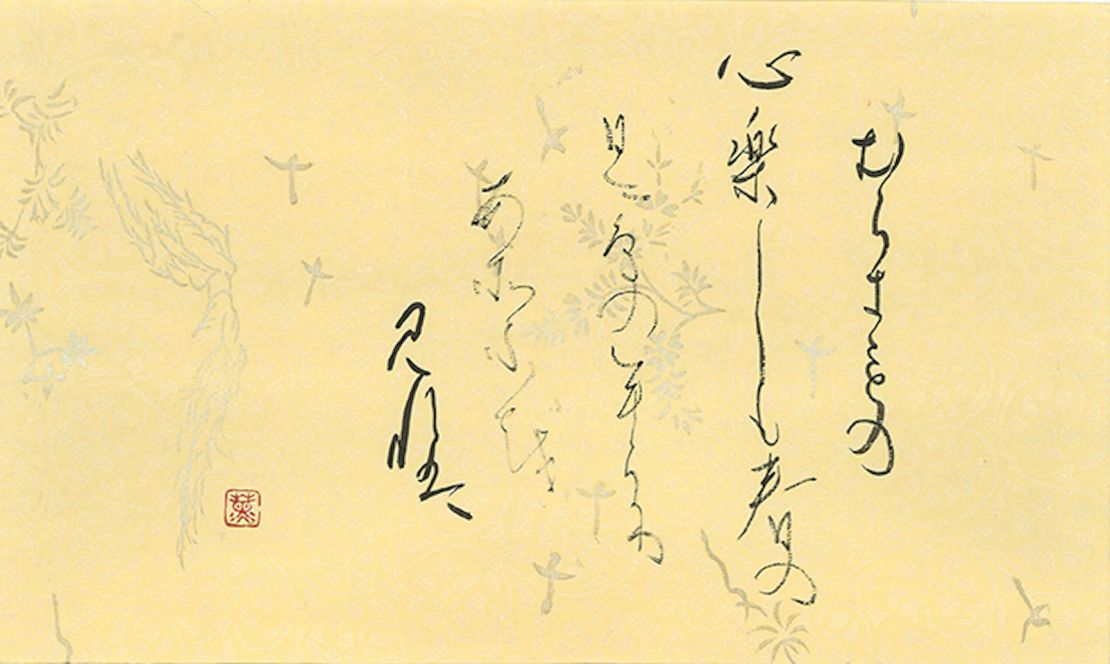

With its undulating, cursive lines, kana shodo appears to stream down whatever surface it graces. According to Akagawa, women of the court competed with one another to invent their own signature designs for characters. Considered a language native to Japan, it was seen as a vehicle through which women could express themselves and document their observations of the world.

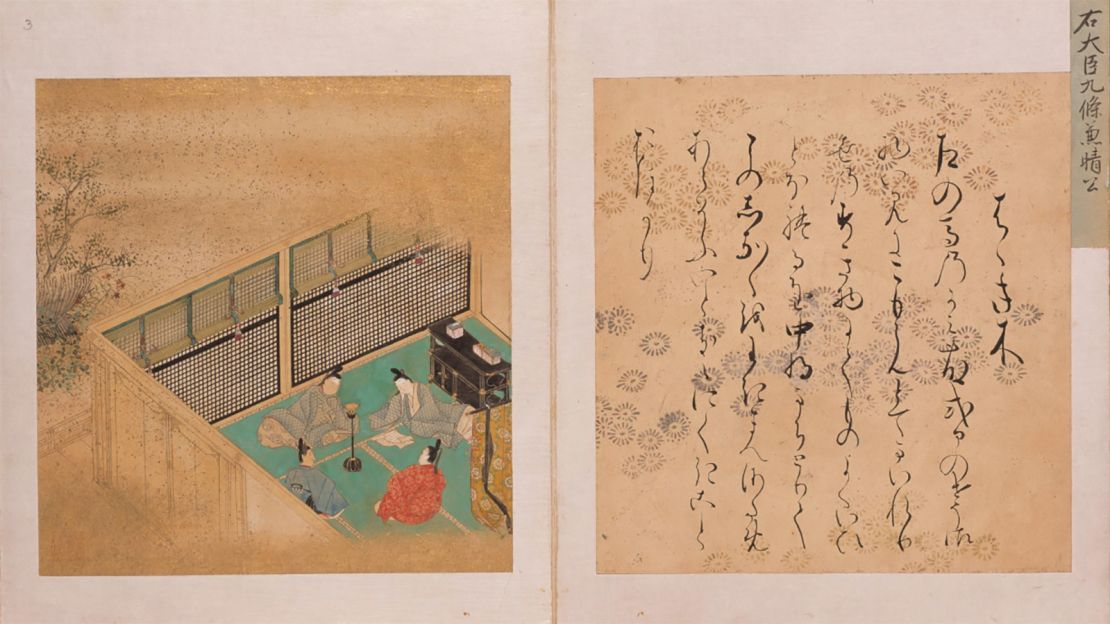

Kana calligraphy was even used to write the 11th century epic tale “The Tale of Genji,” which is often called the world’s first novel as it was one of the first major examples of long-form fiction, and was authored by a woman – lady-in-waiting Murasaki Shikibu.

Kana script was used right up until the 20th century, when the Japanese government standardized writing. Only 46 of the more than 300 kana characters were kept in modern written Japanese.

As fewer people pursue ancient Japanese calligraphy, Akagakawa – now a master calligrapher – has made it her mission to keep this fast disappearing women’s script alive.

The ‘female hand’

In ancient times, the Japanese did not have their own writing system. Kanji characters – which now are the foundation of modern Japanese script – originated from the Chinese script known as “hanzi,” which some experts suggest entered Japan via the Korean Peninsula as far back as the third century.

And though kanji shodo is referred to as “Japanese calligraphy,” in reality, it is “Chinese calligraphy practiced in Japan,” according to Akagawa.

“It is crucial to understand that the text used as material in kanji shodo were always in Chinese language. Kanji shodo in ancient times was considered a foreign language,” says Akagawa.

Back then, literacy in ancient Japan was not widespread and, for the most part, it was men from the ruling classes who learned kanji, known as “man’s hand,” for use in official letters and to read Buddhist sutras.

It was considered improper for noble women to learn kanji as they didn’t partake in official duties. There were, of course, exceptions. Murasaki Shikibu’s father, for example, allowed her to be educated alongside her brother.

According to Akagawa, many noble women knew how to read kanji, but as they were not expected – and sometimes not even allowed – to use it, they fostered their own outlet.

Kana calligraphy was adapted from kanji calligraphy and another phonetic system called “manyougana” – also adapted from Chinese script and considered the oldest native Japanese written script before it became obsolete. But manyougana was considered too complex, so noble women seized on kana, which was much more flexible and easier to write with.

When kana shodo meets art

Women used it to show their position as free-thinking, sexually-liberated intellectuals, within the constraints of 10th-century Japanese court life. They did this by publishing their literary works and openly using kana calligraphy to reflect their personalities in their diaries and the love letters they exchanged with noble men.

Not only was the content of kana and kanji different. The two writing systems looked distinct, too.

“Typically, in kanji shodo the characters are written in straight parallel lines without empty space. By contrary, kana shodo are typically written in slightly fluctuating lines often with empty space so that the lines are scattered in the composition,” says Akagawa.

“Furthermore, the characters in kana shodo are interconnected with each other to make it look more feminine and fluid.”

According to Akagawa, people discouraged men from using kana shodo. She gives the example of Ki no Tsurayuki, an aristocratic courtier who had to pretend he was a woman when it came to expressing himself in kana shodo in his diary.

Men at the time were expected to write diary entries in kanji shodo using Chinese language – which was considered a foreign language – but Tsurayaki wanted to write his personal feelings in his own language of Japanese. He chose to write his diary from the year 935 – now known as “Tosa Nikki” – in kana shodo, pretending that he was a woman, says Akagawa.

“The famous first sentence in Tosa Nikki goes as follows: “I, a woman, would try writing a diary like men, too”. The fact that he was not able to write it as a man depicts clearly that publishing personal literature in kana shodo was considered inappropriate for men in the 10th century,” says Akagawa.

A landmark for women

During the Heian period (794-1185), poetry about love or the beauty of nature took off among the aristocracy.

In Japan, there is a famous anthology entitled “100 Poems by 100 Famous Poets” featuring work from the country’s top intellectuals between the seventh and 13 century, said to have been completed around 1237.

According to Akagawa, before the creation of kana almost all the poets in Japan were men. But the anthology marks a milestone for women of that era, as it features 21 female poets.

“21% of the best-known intellectuals were women. That’s amazing because now we’re struggling to get the female manager role to hit 30% by 2020,” says Akagawa. Japan ranked 110 out of 149 countries in the World Economic Forum’s index measuring the degree of gender equality.

Both Murasaki Shikibu and Sei Shonagan, whose novel “The Pillow Book” provides a witty account on the intrigue of court life, are featured in the seminal poetry anthology. They helped drive kana culture and are recognized as having shaped Japan’s literary canon.

“Medieval women enjoyed free love and free sex. In certain ways, they were more free than Japanese women are now in the 21st century,” says Akagawa.

As the samurai (Japanese warrior class) became more powerful at the end of the Heian era, the government expanded its military. Consequently, men became more powerful and women were expected to follow them and take care of the family and household, says Akagawa.

As women’s role in society changed, so too did their use of kana shodo. It became less of a means of intellectual and literary expression.

Japanese aesthetic

Akagawa, 47, has practiced kana shodo for two decades and is now one of the youngest master calligraphers in Japan, in which the average age of a highly accomplished master calligrapher is usually 60 and above.

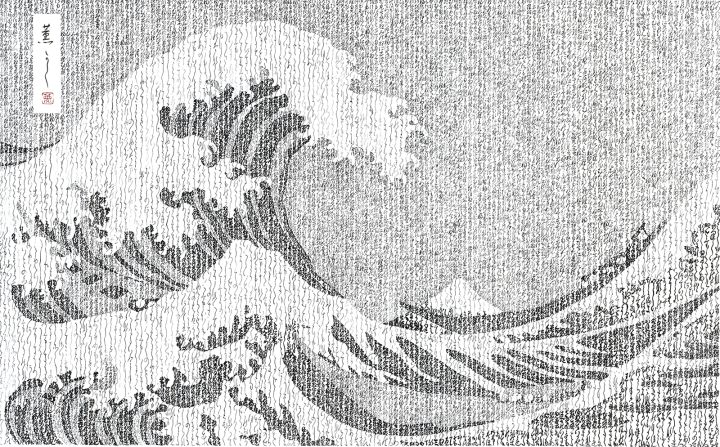

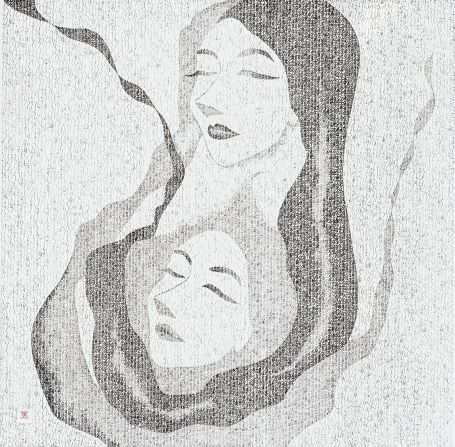

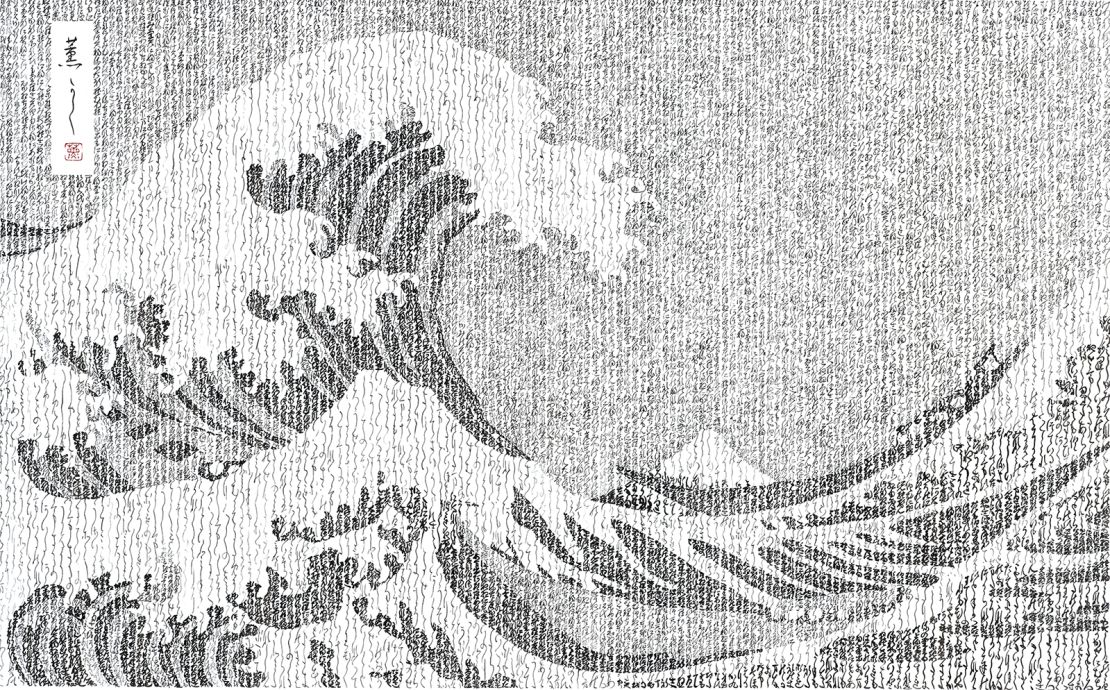

She melds kana shodo with new techniques in a style she calls kana art, where thousands of intricately interwoven kana meld to form larger images, which take months to complete.

But at first, it wasn’t so easy to convince Western audiences that what she drew was calligraphy.

“I was really shocked because people said, That’s not Japanese calligraphy that’s scribbling,” said Akagawa. “They wanted to see kanji shodo, but that is not Japanese language.”

Akagawa says that appreciation for kana shodo has a long way to go, but that in Japan, it still has had a lasting influence. Sometimes it appears in surprising places.

She points to how the ancient script’s emphasis on empty space between characters have carried into the aesthetics of Japanese woodblock prints. And how seminal literary works, such as “The Tale of Genji,” still popular today, were originially written in kana. There are subtler nods too – kana is found as a subtle design element on traditional Japanese sweet wrappings and on the signage of Japanese noodle “soba” restaurants.

Few realize this, says Akagawa, as the fast-paced nature of modern life can prevent people from taking in their surroundings.

In that context, for Akagawa, kana shodo embodies what she calls “the beauty of inefficiency” and represents a time when noble classes – far removed from the grind of daily life – had the time for creative introspection that gave rise to kana.

“In the Heian era, people took time to think about which characters to use in which occasion, there is no rule to choose your kana characters,” says Akagawa. “It just depends on your inspiration and your aesthetic.”