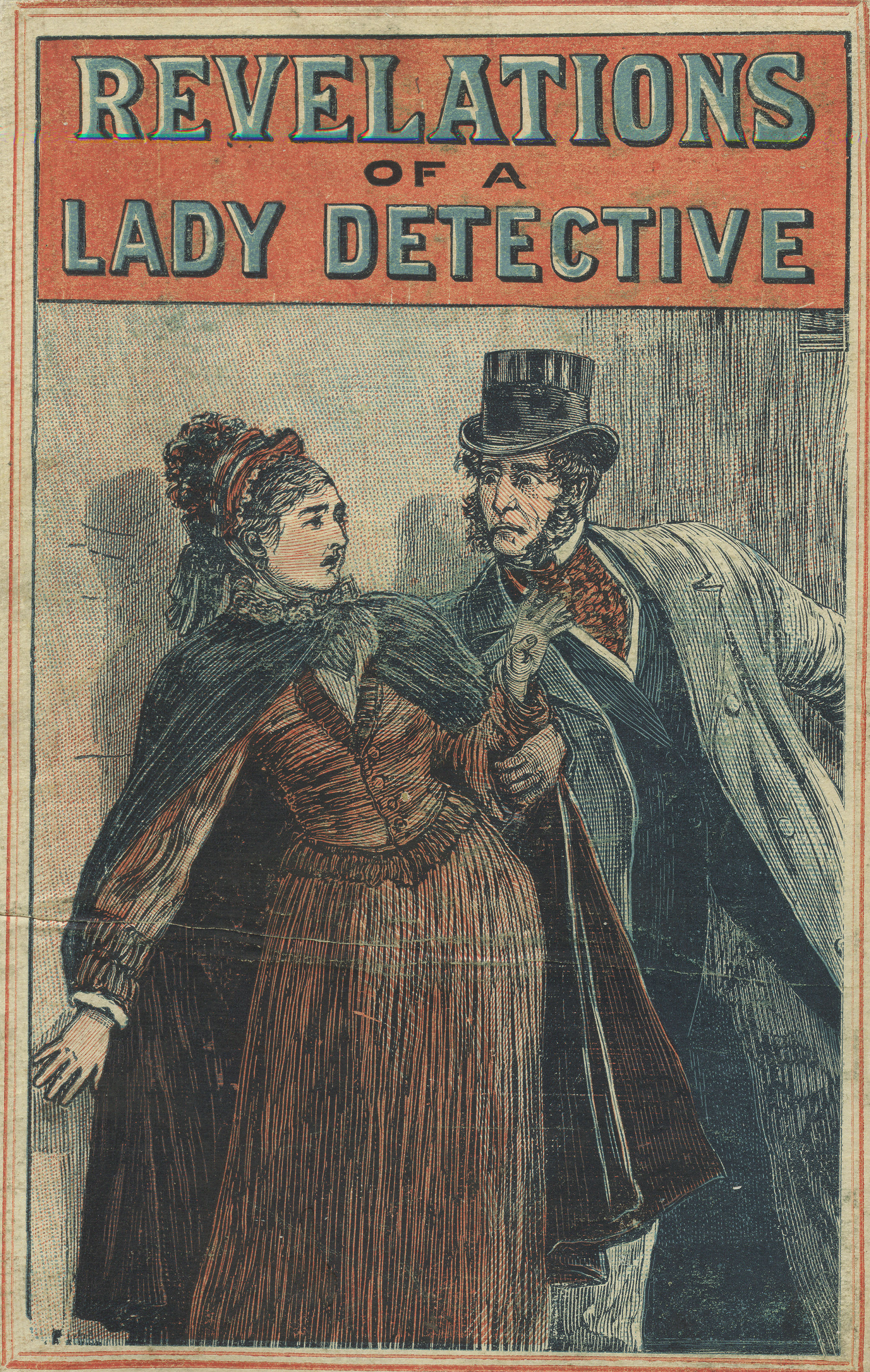

William Stephens Hayward, Revelations of a Lady Detective (C.H. Clarke, 1884). Flickr.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

In “The Council of Four,” an 1897 story by the journalist George R. Sims, a playwright named Saxon walks into his solicitor’s office to find a young woman already inside. Saxon hurries back out, and later apologizes to the lawyer for interrupting the meeting, only to have him gush about his guest: “That, my dear fellow…is Dorcas Dene, the famous lady detective.”

Saxon is awed upon hearing the solicitor’s descriptions of Dorcas Dene’s professional successes and renown and realizes they had met years before. When they reconnect, Saxon, amazed by her powers of deduction and disguise, asks to accompany her on future detective adventures. He, knowing a good narrative when he finds it, begins to write them down.

Victorian readers of Sims’ story surely recognized this gambit from the mega-bestselling Sherlock Holmes series (although at the time of Dorcas Dene’s debut, Holmes had been dead four years, albeit only temporarily; Arthur Conan Doyle wrote him off the side of the Reichenbach Falls in the 1893 story “The Final Problem”). This stylistic trick provides the story with its own endorsement: Sims, like Conan Doyle, stresses the readability of his series by making its narrator so addicted to it. Borrowing this framework may have been a gimmick to hook readers, as many stories that echoed Conan Doyle’s were fashioned to catch the runoff of his success. But, in a neat, anachronistically feminist twist, this similarity places Dorcas Dene on equal footing with the greatest (male) detective known to literature.

Dorcas is not merely a detective: she owns her agency, a business willed to her by her late employer, a police commissioner turned private eye. She is also her family’s provider. Her husband, Paul, is blind, and her labor supports them, her mother, and their (unfortunately named) rescue dog, Toddlekins.

Because of all these details, Detective Dorcas Dene may seem like a standout in the midst of contemporary literature. But she isn’t.

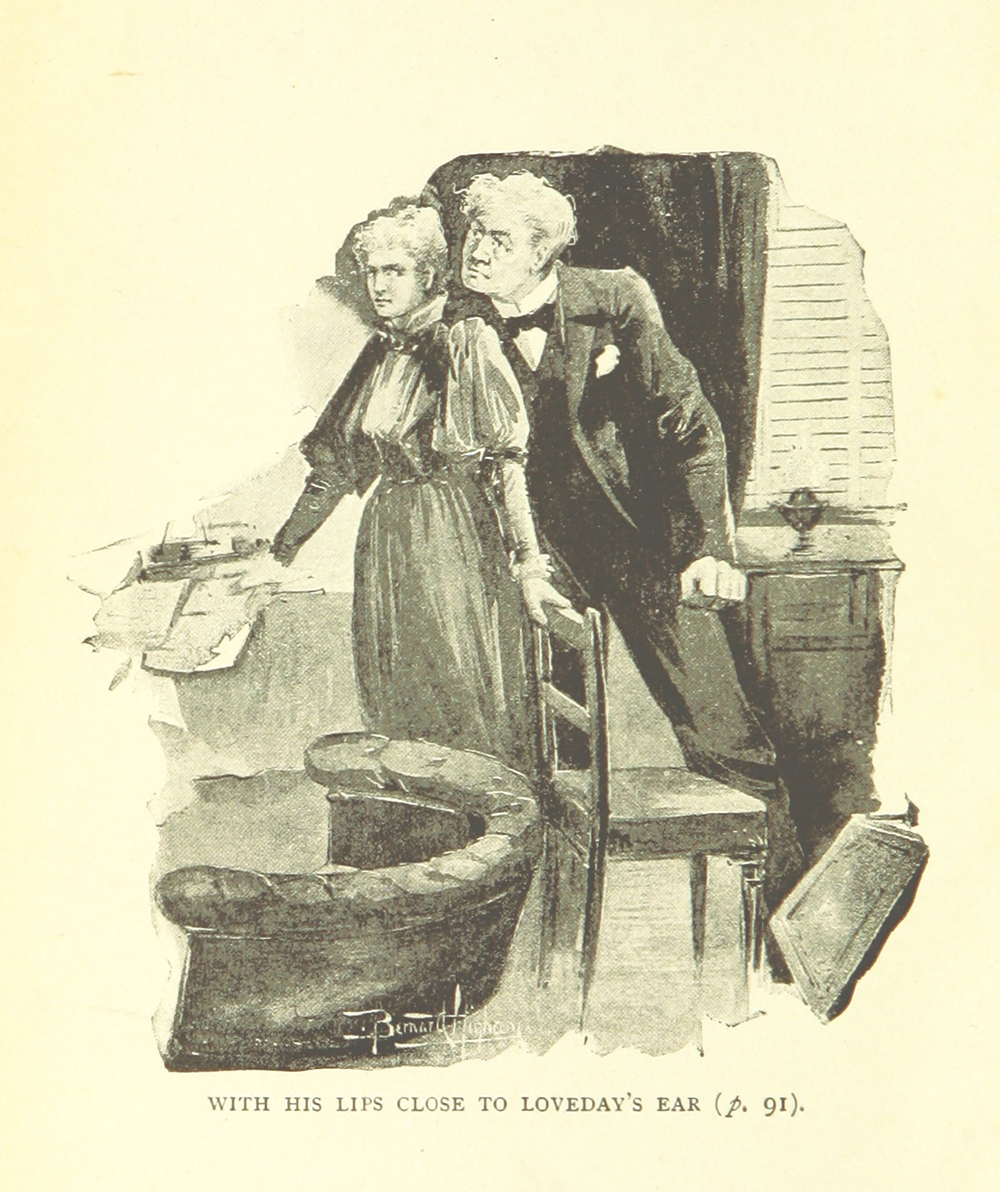

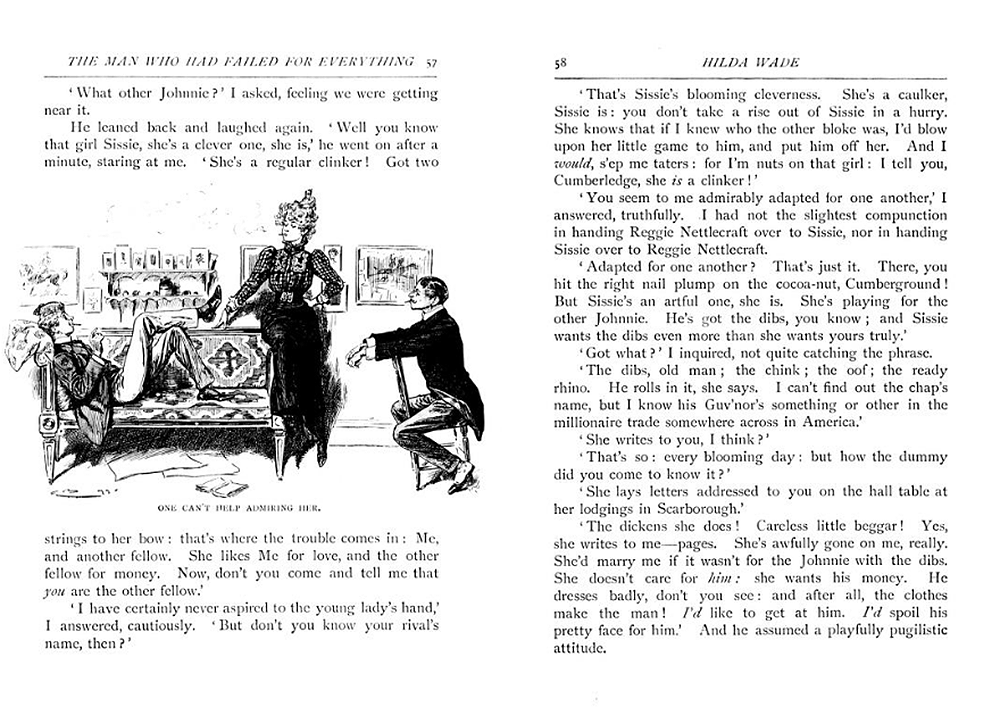

The Victorian era (1837–1901) witnessed the appearance of an overwhelming number of female literary detectives. The rush began in the 1860s with the publication of Revelations of a Female Detective, which featured the debut of Mrs. Paschal, a detective of “vigorous and subtle” brain who works for an all-women branch of the police department. In the following years, readers could follow, in both standalone novels and serializations, the investigative adventures of many other women, mostly based in London. Mollie Delamere (who appeared in a novel in 1899), a young widow employed as an international pearl broker, must outsmart the countless burglars after her wares. Hilda Wade (1900) was a genius nurse solving medical mysteries to get close to the physician who framed her late father for murder and who ends up on a globetrotting adventure to catch him. Dora Myrl, who first appeared the same year, was a youthful woman in ankle-showing skirts with an advanced degree in mathematics from Cambridge. A medical doctor who couldn’t find work as a physician, she begins working as a private eye. There are also Mrs. G–– (1864), Miriam Lea (1888), Loveday Brooke (1893), Rose Courtenay (1895), Lois Cayley (1899), Hagar Stanley (1899), Florence Cusack (1899–1900), Bella Thorn (1903), Lady Molly Robinson-Kirk (1910), and Judith Lee (1911–16). American (mostly New York–based) counterparts included Clarice Dyke (possibly 1883), Laura Keen (1892), Amelia Butterworth (1897), Nora Van Snoop (1898–99), Frances Baird (1906), Madelyn Mack (1914), Violet Strange (1915), and Millicent Newberry (1917). Often left out of this canon, but nonetheless relevant, is Mina Harker, the protagonist of Bram Stoker’s 1897 novel Dracula (a detective story alongside all else), who tracks down the vampire after he flees London.

This abundance of detective heroines manifested as part of a flourishing in the publishing industry, produced by “mechanized composition, cheaper paper, and photomechanical reproduction and such cultural shifts as universal education and widespread literacy,” explains Elizabeth Carolyn Miller, a professor at UC Davis. Magazine publishing, in particular, was extremely fruitful; researcher Peter Keating has observed that from 1875 to 1903, the number of printed magazines in Britain nearly quadrupled (from 675 to 2,531 circulating periodicals). Many magazines had nonstop literary content—short stories and serialized chapters from novels—as writers churned out material for publication that reflected public demand and cultural interest. The genre drew writers of all literary backgrounds, from William Stephens Hayward—the author of the Mrs. Paschal stories about whom we know almost nothing—and science writer Grant Allen (who dictated the last Hilda Wade story to his friend Arthur Conan Doyle on his deathbed) to Leonard Merrick, who hated his detective story, the Miriam Lee–featuring Mr. Bazalgette’s Agent, so much that he attempted to buy every copy in circulation and destroy them. (He missed only seventeen.) The writers of these stories were, unlike their protagonists, mostly men.

The detective craze, which sent countless, reproducible gumshoe stories into print, was in large part an outgrowth of the highly popular sensation novel genre that began decades earlier. Those stories often involved mysteries or sinister criminals and began to feature detective figures. Wilkie Collins, Charles Dickens’ protégé and a master of the sensation novel, included female investigation-inclined protagonists in his works as early as 1856, with his story “The Diary of Anne Rodway.”

Still, there were certainly many more male detectives solving crimes in novels and the pages of popular literary and cultural magazines such as The Strand, The Cornhill Magazine, or Ludgate Monthly, including Edgar Allan Poe’s C. Auguste Dupin (1841–44), Dickens’ Inspector Bucket (1852–53), Rudyard Kipling’s colonial policeman Strickland (1887–1901), “the man hunter” Dick Donovan (1888–96), teen wonder Sexton Blake (1893–1978), Holmes’s main literary rival Martin Hewitt (1894–1903), the “rule of thumb” detective Paul Beck (1898–1929), and Dixon Druce (1902), a bland detective whose more interesting nemesis is an evil cosmetics entrepreneur named Madam Sara. In her book Detecting the Nation: Fictions of Detection and the Imperial Venture, CUNY professor Caroline Reitz points out that decades earlier, from the 1830s to the 1850s, there were also many stories published about the real-life colonial policeman William Sleeman, the superintendent of India’s “Thug Police,” who worked to suppress the Thuggee, the bands of Indian devotees to the goddess Kali who allegedly robbed and murdered travelers. (Reitz has established that while most detective stories from this time took place in the West, their representations of domestic policework still supported the concurrent colonial and imperial agenda. It’s also worth mentioning that all of these detectives, male and female, were white.) But this feast of detective heroines, has, for literary scholars, complicated an already knotty impression of Victorian conceptions of femininity.

Endemic to the Victorian and Long Edwardian (1901–14) eras were two clashing conceptions of female purpose, ability, and power. One approach insisted that the woman be the keeper of the domestic sphere and cultivator of its related moral and civic pursuits (charitable causes, family concerns, etc.), while the other, increasingly popular sentiment demanded female equity with men on numerous grounds: legal, political, economic, social, and academic. The latter attitude, often associated in modern cultural memory with the suffragists who fought for women’s right to vote, was embodied by the paradigm of the “New Woman,” a real-life female archetype characterized by good education, economic independence (i.e., employment), and physical freedom (including “rational dress” and bicycle riding). Or, as Birgitta Berglund at Lund University has explained, this intense divide can be broken down into basic terms: woman as object versus woman as subject.

It makes sense, then, to read these gumshoes against the grain of Victorian conventions. The late J.A. Kestner, a professor at the University of Tulsa, has suggested that the appearance of the female detective (surely the steampunk enthusiast’s literary chimera) in such hefty numbers is a bold and transgressive phenomenon reflecting a collective cultural daringness born partly from the emergence of the “New Woman.” Female typists and cyclists, meet lady detectives.

Scholars argue that these fictional Victorian women are more than culturally displaced proto-action heroines. For one thing, as Mrs. Paschal’s gig helps remind us, these detectives require a suspension of disbelief that their male counterparts don’t: in real London, women were not allowed to work as detectives—and wouldn’t be until legislation was introduced well after all these stories had been written.

Researcher Michele Slung has pointed out that London’s centralized Metropolitan Police Department (which was founded in 1829—yes, that is how young Britain’s oldest police department is, only ten years older than the first American one) didn’t even have any women on staff at all until 1888, when two women were hired to help manage female prisoners. The next woman to be hired was Eilidh MacDougall in 1905; she worked with the Criminal Investigation Department to take statements from women who had been assaulted but was not an officer. A volunteer group called the Women’s Police Service was founded in 1914. London did not have female police officers until a 1916 Act of Parliament (which went into effect in 1918) specifically allowed for it. The first time female police officers were seen in London was in 1919, at a department memorial. Of about twenty thousand officers, only twenty-five were women, though fifty more were hired within the year. Female policewomen had to be between twenty-five and thirty-five years of age and single. If they chose to marry, they were asked to leave the force.

The first female detective position was created in 1922, many decades after the Detectives Department (which became the CID in 1878) was established circa 1842. As expected, male officers were not happy. William Rawlings, deputy commissioner of the CID, said his colleagues regarded the appointment of women as “an invasion.”

All of the female detectives in this literary canon predate these appointments, making their representations even more fabricated than those of their equally fictional but male counterparts. The Victorian era’s fictional male detectives stand on the shoulders of real male police officers whose precedent and authority imbue the fictional counterparts with a modicum of realism. But much of the detective work completed by fictional lady investigators is based on assumptions of what a female investigator would be like—and this means that such characterizations are often rooted in stereotypes about female abilities and interests, rather than observations about objective unisex workloads and professional expectations.

The Oxford University professor Laura Marcus has claimed that these female detectives thrive because of these highly (often made-up) feminine-associated qualities, which prompt potential clients to seek them out.

These private eyes have a “woman’s intuition,” a vague facility of the female mind enabling them to make accurate judgements about others based on little information. That was not always considered a superior quality. In 1871, while writing about the “difference in the mental powers of the two sexes,” Charles Darwin claimed, “It is generally admitted that with woman the powers of intuition, of rapid perception, and perhaps of imitation, are more strongly marked than in man” and “characteristic…of a past and lower state of civilization.”

But this quality is amazing enough that the narrator of the Hilda Wade stories keeps checking to make sure he isn’t witnessing “witchcraft.” Hilda has “so large a measure the deepest feminine gift—intuition” that she is hired to work alongside a celebrated professor of medicine. Although her ability is slammed by a colleague as being “rapid and half-unconscious inference,” and considered by the narrator to be “the other side of the same endowment in its masculine embodiment—instinct of diagnosis,” she successfully uses it to uncover guilty parties, solve causes of death, and evade danger repeatedly, including escaping via bicycle from rioting warriors in the desert with a rescued orphan baby in her arms. (Hilda herself wasn’t above deprecating her own acumen, saying her intuition lacked a “train of reasoning.”) But the application of “intuition” as a crime-solving methodology belies its womanly nature—all detectives use it.

Another necessary feature of the lady detective is her meddlesomeness, an inclination toward knowing all there is to know about the lives of others. This is, of course, a spurious quality; female detectives are seen as exceptional among women for being able to make nosiness and rubbernecking serve the greater good. Obviously, the inability to mind one’s business would come to define detectives of the future. Many Victorian and Edwardian literary detectives have offices where clients or befuddled cops may seek them out or are police officers themselves. But many of the twentieth century’s detectives, from Lord Peter Wimsey and Miss Marple to the “meddling kids” accompanying Scooby Doo, stick their magnifying glasses where they don’t belong—to the ire of criminals and often the consternation of the police. Of these Victorian ladies, no one is more of a busybody than Judith Lee, a young teacher of deaf students, who lip-reads the conversations of others across crowds to locate suspicious behavior.

Miller points out that most of these fictional detectives are there out of necessity, due to the absence or ruin of a supportive man. Dorcas Dene’s breadwinning husband is blind, so she must use her skills to furnish their income. Mrs. Paschal’s husband is dead. Nora Van Snoop is obsessed with finding the man who shot her fiancé. Hilda Wade starts detective work to avenge the wrongful arrest and death of her father; she finds him but quits detection immediately after, she becomes engaged. Lois Cayley starts out solving mysteries out of boredom and financial need, but ends up battling with a criminal mastermind to clear the name of her framed lover.

Loveday Brooke, a fearless single young woman who solves crimes purely for her own reasons, may be the exception that proves the rule, Miller suggests. Much like all these women, she is heralded by her male supervisor for having “the faculty—so rare among women—of carrying out orders to the very letter…a clear, shrewd brain, unhampered by any hard-and-fast theories” and “so much common sense that it amounts to genius—positively to genius.” More than that, Miller argues that she is also a proto-feminist presage; rather than illuminating gender oppression, she expands Victorian conceptions of nongendered potential. Brooke—whose stories also feature progressive representations of both female labor and contemporary criminality, according to Miller—was the brainchild of Catherine Louisa Pirkis, a well-respected and prolific author, one of the few women to write entries in this canon. Other female authors include L.T. Meade, co-creator of Florence Cusack and Dixon Druce/Madame Sara; Anna Katherine Green, author of the Amelia Butterworth and Violet Strange mysteries and before that the bestselling author of the Ebenezer Gryce mysteries; and Beatrice Heron-Maxwell, who was widowed and had to fashion a career suddenly, much like her heroine Mollie Delamere.

While Brooke might be the clearest example of a productive Victorian treatment of female capability, many other heroines seem to make an effort. Perhaps the best example is Judith Lee (whose prolific author, Richard Marsh, wrote the horror novel The Beetle, which outsold Dracula when they were published concurrently in 1897). In Judith’s inaugural story, she narrates a flashback to her first case, when a very young Judith is caught lip-reading a conversation between local criminals. The (male) criminals proceed to tie her up and, before leaving her for dead in an empty house, cut off her hair to scare and shame her. She manages to help catch them but is nonetheless traumatized. Every subsequent story shows Judith getting stronger and more tenacious, even learning jujitsu (yes, jujitsu). Judith’s career is shaped by male forces, but she manages to avenge herself with her detective side job.

In a 1914 episode titled “The Restaurant Neapolitan,” nine stories into her twenty-two-story career, Judith gets caught in a brawl with some local mafiosos after the discovery of a dead body on the street leads her to a woman imprisoned above a mob-owned London restaurant. The rescuer and rescuee, wielding knives and fire pokers, beat up the members of the gang. Judith continues to fight even after her opponent has stabbed her and defeats him. This is not the only time when she threw herself into such conflicts—she frequently tussles with male and female criminals, often at serious personal risk. Once she is thrown off a boat near the coast of Morocco, swims ashore, and walks four days to Tangiers.

Many of these female detectives do not conform to gender expectations, mainly because they operate in an archetype that is hard to gender at all. The detective, new as both a profession and as a literary archetype, was a gray-area outfit with only one qualification: outstanding problem-solving abilities. Thus, many detectives, male and female, greatly resemble one another. G.K. Chesterton’s Father Brown (1910–36) operates on an “intuition” highly similar to Hilda Wade’s. Sherlock Holmes is a master of disguise, and so is Dorcas Dene. The very point of the detective is to defy the trappings of normalcy and do extraordinary work; if this were not the case, then the regular police constabulary would have no trouble solving the crime at hand and locating the perpetrator on their own.

The only difference between Dorcas Dene (“a brave and yet womanly woman”) and Sherlock Holmes is that she imposes restrictions of respectability on what work she will do and he does not. “If I found that being a lady detective was repugnant to me,” Dorcas tells her narrator, “if I found that it involved any sacrifice of my womanly instincts—I should resign, and my husband would never know I had done anything of the sort.”

Despite the plethora of such figures within this genre, the female detective is fundamentally isolated. In most of these stories, she is the only exceptional woman of her kind within her world, and in many cases she is presented as some sort of prize among her gender. But the lack of crossover, collaboration, or community among such female characters within their novels also means that these characters are pitted against each other, with the reader as their judge. Forcing them to become one-off, replaceable iterations of the same archetype bars the notion that many women may be just as impressive, effective, productive, or suited to such jobs. Imagine what these detectives could have accomplished, professionally and culturally, if they were allowed to work together.

Some of these stories seem to push back against this forced solitude. In a Loveday Brooke story, a woman observes that “lady detectives…are a race apart” from the rest of the gender—othering them for their exceptionalism, sure, but also acknowledging their potential plurality. Mrs. Paschal, the first official lady detective in literature, works in an entire department of female sleuths, a concept, she says, that has been adapted from the French for its incontrovertibly favorable impact. These “petticoated police,” she says, “were as successful as the most sanguine innovator could wish.” Only a backward police department, she seems to suggest, would pass up their skills.