For more on Justice Ginsburg, watch CNN Films’ “RBG” on Sunday, September 9 at 8 p.m. ET/PT.

There is something in the current “Notorious RBG” fervor that offers the perfect paradox for a woman whose early career was marked by rejection and work in the trenches of anti-discrimination law.

Ruth Bader Ginsburg’s superstardom has not been fleeting, precisely because of what she did before and what she represents today.

She made the law review at both Harvard and Columbia law schools and graduated at the top of her class at Columbia. Yet she was rejected for the most prestigious judicial clerkships and spurned by law firms. It was not just that she was a woman. She was also a mother caring for a young daughter.

But that was nearly six decades ago, and on Friday, Ginsburg marks the 25th anniversary of her judicial oath on the US Supreme Court.

When she failed to land a law firm job, she turned to teaching, then became a women’s rights lawyer and eventually won a federal appeals court seat. As a Supreme Court justice since 1993, she has authored scores of opinions that have helped set the course of the law, particularly on equality rights. She wrote the landmark ruling that forced the state-run Virginia Military Institute to admit women.

Now it is her scorching dissents that draw most public attention.

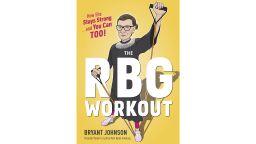

Popular culture has embraced the RBG phenomenon, perhaps because the woman who crusaded against sex discrimination is now a vocal dissenter on a high court that is becoming increasingly conservative.

She is also an original member of what is today’s #MeToo movement, recounting her own experiences as a pathbreaking woman on campus and in the workforce.

The “Notorious RBG” meme, a play on the late rapper Notorious B.I.G., was created as a response to a 2013 dissent Ginsburg wrote when the court majority issued a milestone decision rolling back voting-rights protections. Ginsburg’s dissents continue to energize Democrats, at a time when Republicans control the executive and legislative branches of government and the Supreme Court moves rightward.

From films to action figures, the entertainment world has shown a fascination with the trailblazer who changed the course of women’s rights and at age 85 still pumps iron.

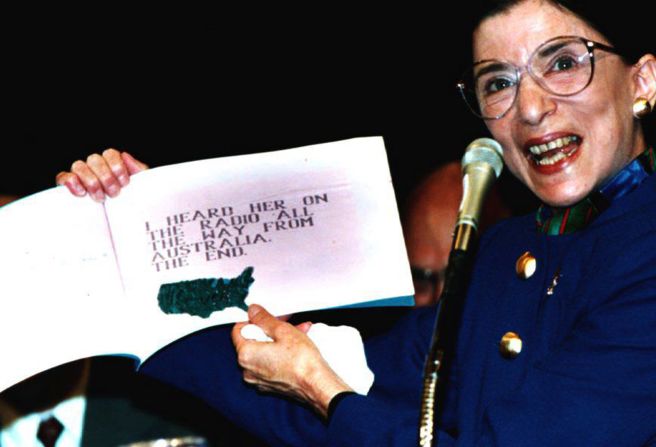

The documentary “RBG,” co-produced by CNN, has made $13.5 million at the box office, according to comScore, and will be broadcast next month on the network. Oscar nominee Felicity Jones will play her in a feature film, “On the Basis of Sex,” in December.

The justice said recently that she hopes to stay on the Supreme Court at least five more years, when she’ll be 90. She has survived two bouts with cancer, colorectal in 1999 and pancreatic in 2009.

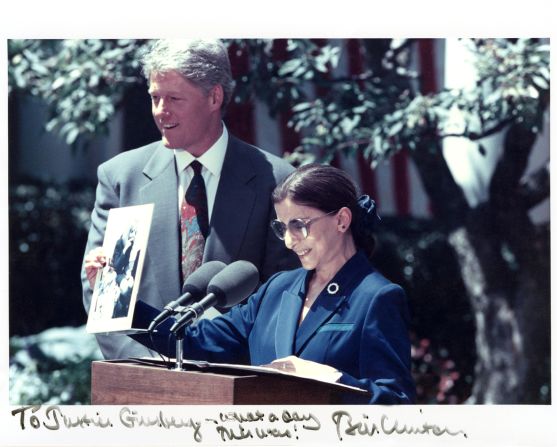

Ginsburg’s celebrity might not have been predicted when President Bill Clinton chose her for the high court in summer 1993.

Then a 60-year-old federal appellate judge, she was not Clinton’s first choice. He was looking for a flashier appointee and initially tried to woo former New York Gov. Mario Cuomo to the bench.

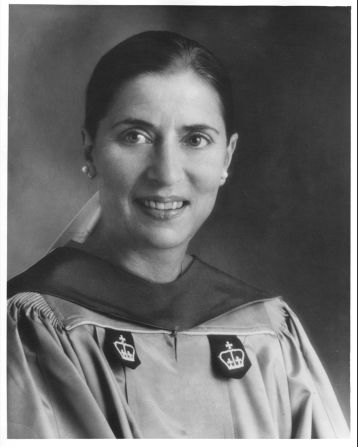

Ginsburg, with her large-rimmed glasses, hair tied back in a short ponytail, presented the picture of seriousness. She spoke of taking “measured motions” as a jurist. Supporters portrayed her as a night owl who spent hours hunched over law books and legal briefs, tepid coffee and prunes at hand. Her daughter created a little book titled “Mommy Laughed,” chronicling the few times it happened.

Once on the Supreme Court, Ginsburg was a sharp questioner and meticulous opinion-writer. She leaned in but without the attention-getting style of the first female justice, Sandra Day O’Connor, or gregarious longtime pal Antonin Scalia.

She was hardly a liberal in the mode of contemporary justices on the left: William Brennan, Thurgood Marshall or Harry Blackmun. But as the court changed over the years and became more conservative with each retirement, she found herself carrying the banner for the left.

It is the lesson of Ginsburg’s eight decades – marked by early loss and professional rejection – that life’s vicissitudes can open unexpected doors and bring new opportunities.

Now carrying a commercial tote bag with the words “I dissent,” she appreciates her icon status. But she still conveys a modest approach. When asked recently during a public appearance how she wanted to be remembered, she said, “As someone who did the best she could.”

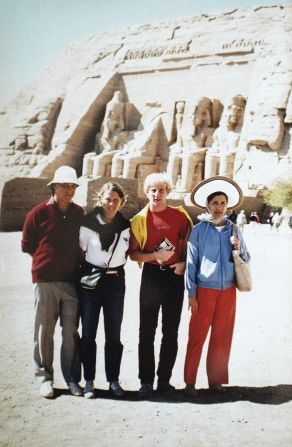

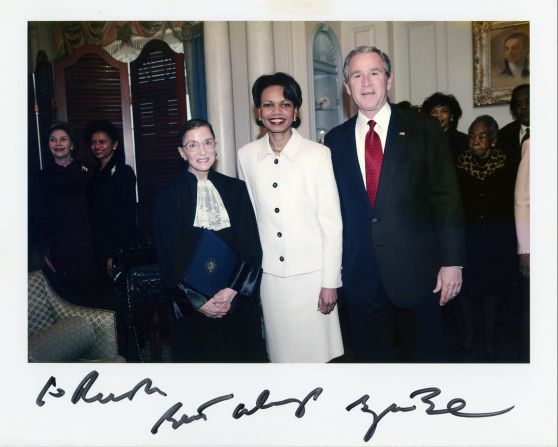

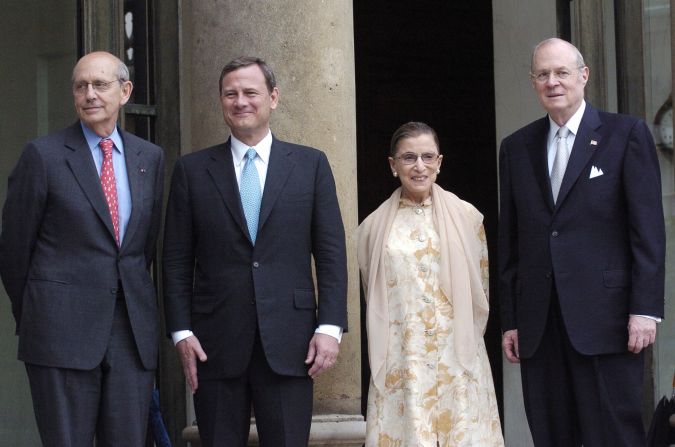

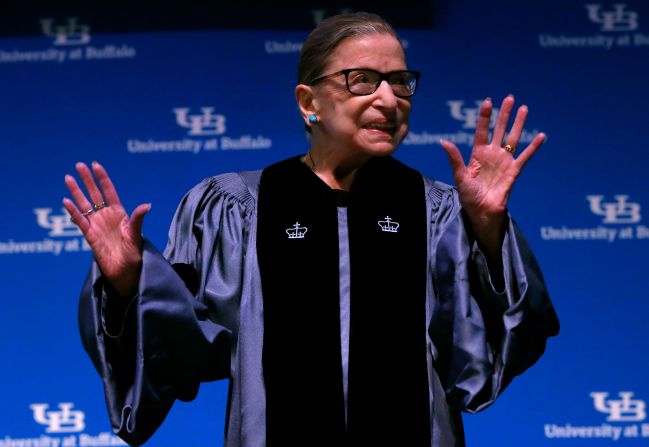

In photos: Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Early life marked by death

Ruth Bader was born in Brooklyn in 1933, the second daughter of Celia and Nathan Bader. Her older sister, who gave Ruth the nickname of “Kiki,” died of meningitis before Ruth was 2 years old. (The justice’s real name was Joan Ruth Bader, but she said that because so many girls in her kindergarten class were named Joan, her mother asked that she be called Ruth.)

Her mother encouraged her to excel in school. But she would not live to see her daughter’s early achievements. Just before Ruth was to graduate from high school with honors, her mother died of cervical cancer. Ruth missed graduation, staying home with her grieving father, and her teachers delivered her various awards to her after the ceremony.

She attended Cornell University on scholarship as a government major. There she met Martin Ginsburg, whom she would later describe as the first boy who “cared that I had a brain.”

They married in 1954 and the following year had their first child, Jane. A second child, James, was born 10 years later.

Ruth and Martin attended Harvard Law School. Ruth began when Jane was a baby, and soon was caring also for Martin, who had been diagnosed with testicular cancer.

She typed up his class notes and helped with his studies, learning to exist on very little sleep, as she kept up with her own studies and attended to daughter Jane. Martin recovered, graduated and landed a job in New York City in 1958.

By that point, Ruth had finished two of the three years of law school. When they moved to New York, she completed her law degree at Columbia University. She graduated in 1959, tied for first place in her class.

She was rebuffed for a Supreme Court clerkship by Justice Felix Frankfurter because she was a woman and then was turned down by major New York law firms. She later wrote that law firms in the 1950s were beginning to hire Jews. “They had just gotten over that form of discrimination,” she wrote. “But to be a Jew, a woman and a mother to boot,” she wrote, “that combination was a bit much.”

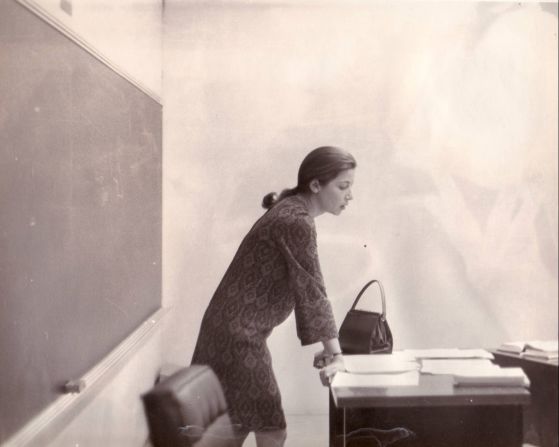

She became a law clerk to a federal district court judge, then worked at Columbia as a researcher. Her early specialty was civil procedure, and she spent several months in Sweden in the early 1960s studying its legal procedures.

The women’s rights movement beckons

While Ginsburg was teaching at Rutgers Law School, from 1963 to 1972, her interest in sexual equality was sparked by the broader women’s rights movement underway. In the early 1970s, she has said in interviews, she realized how few court rulings, commentary and teaching materials covered sex discrimination. In 1972, she returned to Columbia University law school as a professor, the first woman to be named to a tenured position. That year, she also helped found the American Civil Liberties Union’s Women’s Rights Project.

She argued six cases before the Supreme Court, winning five. Her strategy was distinctive. Rather than use only women as plaintiffs to challenge discriminatory government practices, she often chose men.

In an important 1975 case, Weinberger v. Wiesenfeld, the Supreme Court struck down a Social Security law that provided survivors’ benefits for widows with small children but not for widowers with small children.

“The whole ACLU Women’s Rights Project – it would not have been possible 10 years earlier,” Ginsburg said in a 2016 interview.

She said she felt that she was also in the right place in late 1979, when a spot suddenly opened on the US Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia Circuit. Judge Harold Leventhal, then 64, died after suffering a heart attack. “Who could have predicted that?” Ginsburg said. “He was playing tennis.”

Listen to the podcast 'Beyond Notorious'

President Jimmy Carter nominated Ginsburg to the DC Circuit, and she was approved by the Senate in 1980. Ginsburg said later that she had been hoping for a seat on the New York-based 2nd Circuit, where she and Martin were living. But it was fortuitous that she ended up on the DC Circuit, which has become a steppingstone to the high court.

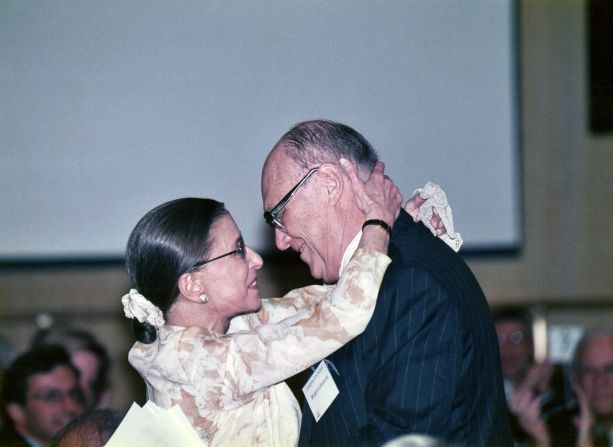

She and Martin, a prominent tax lawyer, moved to Washington, where he began teaching at Georgetown University law school. (Martin died in 2010 of cancer.)

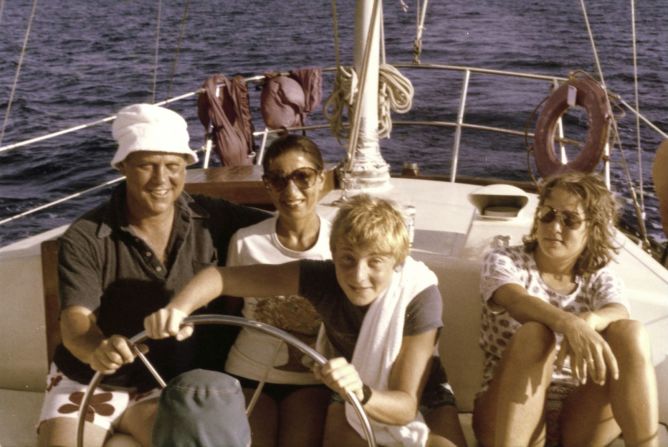

On the influential appeals court that specializes in federal regulatory disputes, Ginsburg was an exacting jurist and moderate liberal. She became close friends with Scalia, whom President Ronald Reagan appointed to the DC Circuit in 1982 and then to the Supreme Court in 1986. Ideological opposites but both former law professors, they enjoyed editing each other’s opinions. Opera lovers and avid travelers, they socialized regularly and, with their spouses, began a tradition of spending New Year’s Eve together.

When Justice Byron White announced his retirement in 1993, Clinton considered several possible candidates, including Cuomo, who decided against what seemed to be the cloistered life of the court. Top aides thought Clinton was then ready to select Judge Stephen Breyer (whom Clinton chose the next year when another vacancy occurred).

Attorney General Janet Reno had been pushing Clinton to meet with Ginsburg. Nearly three months after White had made his retirement known, the President interviewed Ginsburg on June 13.

The next day he formally nominated her in a Rose Garden ceremony. Ginsburg’s life story and background in women’s rights appealed to Clinton, who when announcing the selection emphasized that law firms had rejected Ginsburg because she was a woman raising a child.

He said she represented to women’s legal rights what Thurgood Marshall “was to the movement for the rights of African-Americans.”

When she accepted the nomination, Ginsburg said of her late mother, “I pray that I may be all that she would have been had she lived in an age when women could aspire and achieve, and daughters are cherished as much as sons.”

Ginsburg was approved by the Senate 96-3 on August 3 and took the judicial oath on August 10, becoming the first justice appointed by a Democratic president in 26 years; the last had been Marshall, named by Lyndon B. Johnson in 1967.

A high court evolution

On the Supreme Court, Ginsburg has been best known for her opinions related to civil rights. In her first term, as she joined an opinion (written by O’Connor) that enhanced workers’ ability to prove job discrimination based on sexual harassment, Ginsburg added a concurring statement that underscored the unequal treatment of women in the workplace.

“The critical issue,” she wrote in in Harris v. Forklift Systems, “is whether members of one sex are exposed to disadvantageous terms or conditions of employment to which members of the other sex are not exposed.”

In 1996, she wrote the court’s opinion forcing the state-run Virginia Military Institute to admit women. She said the state’s military school “serves the state’s sons” yet “makes no provision whatever for her daughters. That is not equal protection” as required by the Constitution. The vote was 7-1; only Scalia dissented. Justice Clarence Thomas, whose son attended VMI, did not participate.

In 2017, VMI honored Ginsburg. During a speech to the school’s cadets, she observed that opposition to the Supreme Court ruling had faded when the school saw “how much good women could do for the institution.”

The VMI decision may have been a high-water mark for her on behalf of a court majority. Many of Ginsburg’s civil rights opinions have been, by and large, written as a dissenter.

Since 2010 and the retirement of Justice John Paul Stevens, Ginsburg has been the most senior liberal justice and a robust voice for the left. Her 2013 dissent in a case invalidating a major portion of the Voting Rights Act, Shelby County v. Holder, inspired the Notorious RBG meme, the viral social media brainchild of Shana Knizhnik, then a New York University law student. Mugs and all manner of other retail tchotchkes followed.

She continues to speak boldly through her dissents, but also during interviews. In July 2016, she complained to reporters for The Associated Press and The New York Times about then-candidate Donald Trump, saying she could not take him seriously, and kidded that if he won she might move to New Zealand. Critics said such remarks could undermine her appearance of judicial impartiality.

When asked her if she regretted her sentiment, she only ramped it up. “He is a faker,” she told CNN. “He has no consistency about him. He says whatever comes into his head at the moment. He really has an ego. … How has he gotten away with not turning over his tax returns? The press seems to be very gentle with him on that.”

Trump jumped into the fray, saying “her mind is shot” and that she should resign. Ginsburg ended up putting out a statement, regretting her “ill-advised” remark and vowing to “be more circumspect.”

The day after the November 2016 election, she wore over her black robe the collar (black with silver crystals) she reserves for days in which she issues a dissenting opinion.

Experiences that continue to resonate

While she has since avoided addressing the Trump presidency beyond her judicial opinions, she has continued to speak on the issues of the day. Earlier this year, at the Sundance Film Festival, she praised the #MeToo movement. “I think it’s about time,” she said. “For so long, women were silent.”

She recounted an episode from her days at Cornell, as she prepared for a chemistry test. “My instructor said … ‘I’ll give you a practice exam,’” Ginsburg said. The next day she discovered that the practice exam was, in fact, the real test.

“And I knew exactly what he wanted in return,” she said. “I went to (the instructor’s) office and said, ‘How dare you? How dare you?’ And that was the end of it.”

In an earlier interview, she told me that as a law professor she had trouble getting male colleagues to listen to her. “I don’t know how many meetings I attended in the ’60s and the ‘70s, where I would say something, and I thought it was a pretty good idea. … Then somebody else would say exactly what I said. Then people would become alert to it, respond to it.”

That still occurred when she became a justice, she told me in a 2009 interview. “It can happen even in the conferences in the court. When I will say something … and it isn’t until somebody else says it that everyone will focus on the point.”

Her direct, even defiant, approach has boosted her profile, even as she says she hopes for less division on the Supreme Court.

She remains an optimist. “I have been lucky at every turn,” she says, adding that it may have been for the better that she never landed the law firm positions she sought.

“I would have been long retired from a law firm,” rather than in a life-tenured position on the nation’s highest court. “Things that look bad at the time can turn out to be the greatest thing.”