Lights, cameras, cops.

These are among the new safety measures the British government introduced this week, amid the clamor for safer streets after the abduction and murder of Sarah Everard, 33, this month. The plan includes investing £45 million ($62 million) for additional street lights and video surveillance cameras, and placing more undercover police in bars and night clubs. It is unlikely to work, experts say.

Sue Morgan, executive director of the UK Design Council, for one, is exasperated with what she sees as the government’s myopic response. “Throwing more police at the problem is not the easy answer,” she begins. Morgan underscores the irony of relying on law enforcement when a London Metropolitan Police officer is the prime suspect in Everard’s case. “There are also lots of statistics around proving how police don’t take women seriously—especially young women,” she points out.

A landscape architect and expert in designing inclusive spaces, Morgan says that a wealth of resources for tackling gender violence in streets were developed decades ago. “I’m very, very frustrated as a professional who has worked on the built environment all my life,” says Morgan. “This is just a self-perpetuating systemic issue. The overarching context is that we’re all angry that we still having to have these same conversations.”

The UK Home Office, the government department responsible for public safety, explains that the measures announced this week are just the start. “We recognize that there is more we need to do to tackle the root causes of gendered violence and to support women,” a spokesperson told Quartz. “That is why we have reopened our consultation on violence against women and girls and would encourage everyone to share their views to develop our future strategy.”

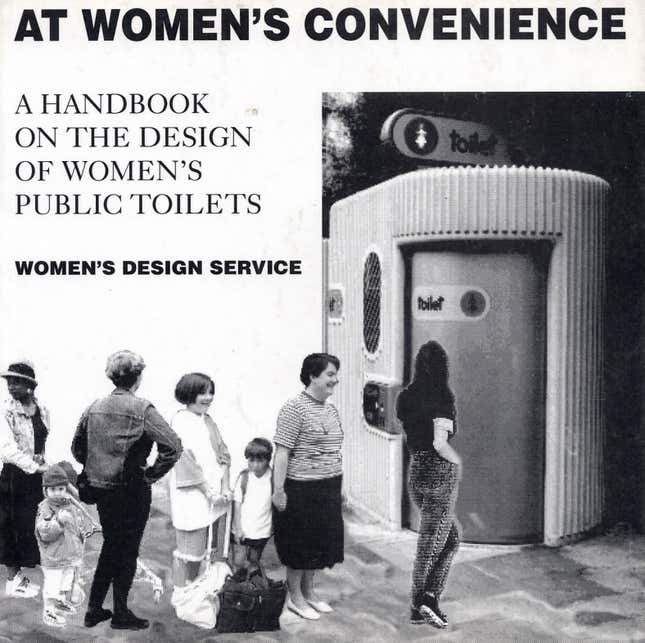

Morgan highlights the work of the now dormant Women’s Design Service, a coalition of British feminist planners, architects, and urban designers who came together in the 1980s to research and lobby for improving the UK’s built environment for women. “Look down the list of their publications and some really important pieces of research are there,” she says. “It’s very sad because there’s clearly stuff in there from 20 years ago that’s still depressingly relevant today.” Before ceasing operations due to lack of funding, the Women’s Design Service tackled issues like improving public toilets, acclimating refugee women, and creating safer parks and streets.

Back in 1961, urbanist Jane Jacobs addressed this very matter in her seminal book, The Death and Life of Great American Cities. Reading her chapter on the uses of sidewalks, one could almost imagine the Canadian-American journalist debating UK prime minister Boris Johnson about his solutions. Jacobs writes:

The first thing to understand is that the public peace—the sidewalks and street peace—of cities is not kept primarily by the police, necessary as police are.

Horrifying public crimes can, and do, occur in well-lighted subway stations when no effective eyes are present. They virtually never occur in darkened theaters where many people and eyes are present. Street lights can be like that famous stone that falls in the desert where there are no ears to hear. Does it make a noise? Not for practical purposes.

Paul van Soomeren, board director of the International Crime Prevention Through Environmental Design association, says it’s a nagging problem around the world. “What astonishes me is that there was a very strong movement of women and men asking for safe and secure public space for everyone as early as the 1970s.” He notes women-led research from the Vrouwen Bouwen Wonen in the Netherlands, Frauenbüro in Austria, and Canadian scholars Gerda Wekerle and Caroline Witzman.

“It is really important to dust off these ideas again,” he says.

Design strategies for safer streets

The core principle of street safety hinges on what Jacobs calls “eyes on the street,” the idea that a busy street—an active “sidewalk ballet,” as she puts it—is the best form of security. “

Van Soomeren says safety-minded urban planners can close down some pathways at night and reroute crowds to one or two arteries. Adequate street lighting is important not just for illuminating pathways. It allows homeowners or shopkeepers to scan their surroundings clearly and act on any criminal activity they see. Empty buses also pose a threat, Morgan points out. “If you go upstairs as a lone woman, the bus driver won’t even know if you’ve been attacked. Again it comes down having other people on the bus.”

Ultimately, we should invest in structures that are inclusive, says Morgan. “It’s about creating spaces where people have an opportunity to spend time in and linger, because the more people in a place, the safer it becomes,” she argues. “It can entail simple things like having benches on a bus stop where you won’t slide off…It’s not rocket science.”

Beyond physical architecture, convincing people to act as custodians of their immediate environment is essential. “Again, one of the big errors is thinking that safety is something only for the police,” says Van Soomeren. “You live in your dwelling, but you also have a responsibility for your neighbors and people in the street.”

Maintenance and upkeep is also essential. This entails keeping streets clean, fixing busted street lights, or trimming shrubbery so they don’t obscure lines of sight. Van Soomeren cites a 2008 study in the Netherlands that demonstrated how people’s behavior is dramatically influenced by the quality of their streets. In streets where graffiti, debris, and broken windows were present, theft, and anti-social behavior increased.

Maintenance could also involve correcting problematic social habits around reporting crime. For instance, in the US, Stanford University social psychologist Jennifer Eberhardt learned how the UX design interface for social networks like Nextdoor fostered racial profiling. By tweaking the interface—updating the oft-cited security slogan,”if you see something, say something,” to “see something suspicious, say something specific”—incidents of racial profiling incidents dropped by 75% within a few months.

The root of the problem

With all the toolkits, research papers, and devoted experts in the UK, why have things not improved? “I think there is still inherently systemic sexism and misogyny in our society, to put it bluntly,” Morgan says.

The lack of diversity in the design industry is core to the issue,” explains Morgan, citing a 2018 Design Council survey showing that 78% of the UK design workforce is male. “If we don’t have women designing places, buildings, and products, how they be inclusive or accessible?”

Morgan says that even the recent protests over the Everard case highlight some systemic issues. “We can’t get over the irony of women politely protesting in the park at night with no toilets and no lighting so they can’t stay longer than 9 o’clock anyway because they can see.”

This story has been updated with comments from the UK Home Office.