Witches are having a major moment. As well as this weekend’s release of the witchy horror movie Suspiria, a slew of witch-themed TV reboots are in the works (see: Charmed, Sabrina the Teenage Witch, and Bewitched). Starbuck’s unveiled its “Witch’s Brew” Halloween frappucino this Halloweeen week. The population of practicing witches and Wiccans in the US has seen an astronomical rise. And social media has conjured up a kind of Instagrammable witchiness that has been identified by market trend-spotters as “mysticore” or “chaos magic.”

The modern incarnation of witch culture in the #MeToo era has a kind of feminist, liberal sheen to it—with millennial women gravitating to witchcraft’s focus on women’s power and sisterhood, inclusivity, and adjacency to broader interests like yoga, meditation, and mindfulness. Followers of Wiccan or Pagan traditions gather in covens, practice moon ceremonies, and occasionally cast hexes on people such as US president Donald Trump and Supreme Court justice Brett Kavanaugh.

And it makes some sense that a culture focused on potions and spells, herbal essences, serums, and elixirs has found a manifestation in the ballooning wellness and beauty industries. From Gwyneth Paltrow’s Goop to the beauty giant Sephora, new age mysticism has been a profitable mainstay for the wellness industry, which has peddled the accouterments of modern witchcraft: tarot cards, anointing oils, and crystals for healing, as well as all manner of dusts, mists, and tinctures purporting to have magic powers to inspire, enchant, or empower. There are even self-care-focused subscription boxes for aspiring witches.

Hashtag communities like #witchesofinstagram have led to the rise of witch lifestyle influencers like the Hoodwitch—complete with sponsorship deals and a web store selling smudge sticks, “Slutist Tarot” cards, and chunks of rose quartz.

But as the wellness and beauty industry dabbles in witchiness, it’s worth paying attention to which part of witches’ long and complicated history it draws upon. Witchcraft has for centuries been associated in the popular imagination with beauty and sexuality, but it hasn’t always been pretty: The term “witch,” has been used as a multipurpose misogynist slur, while witches or those suspected of witchcraft have been persecuted—sometimes violently and sexually—across history and cultures.

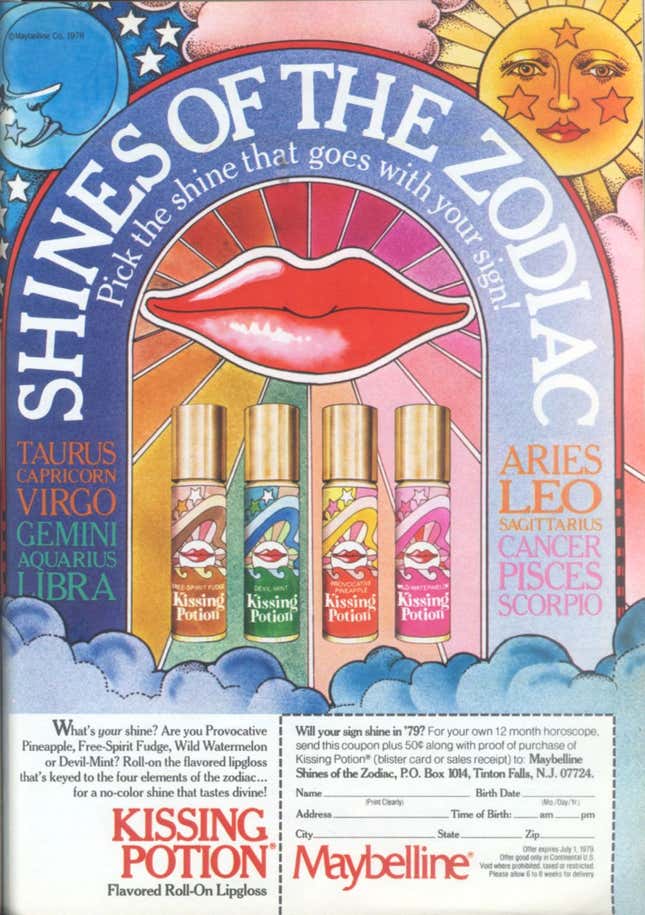

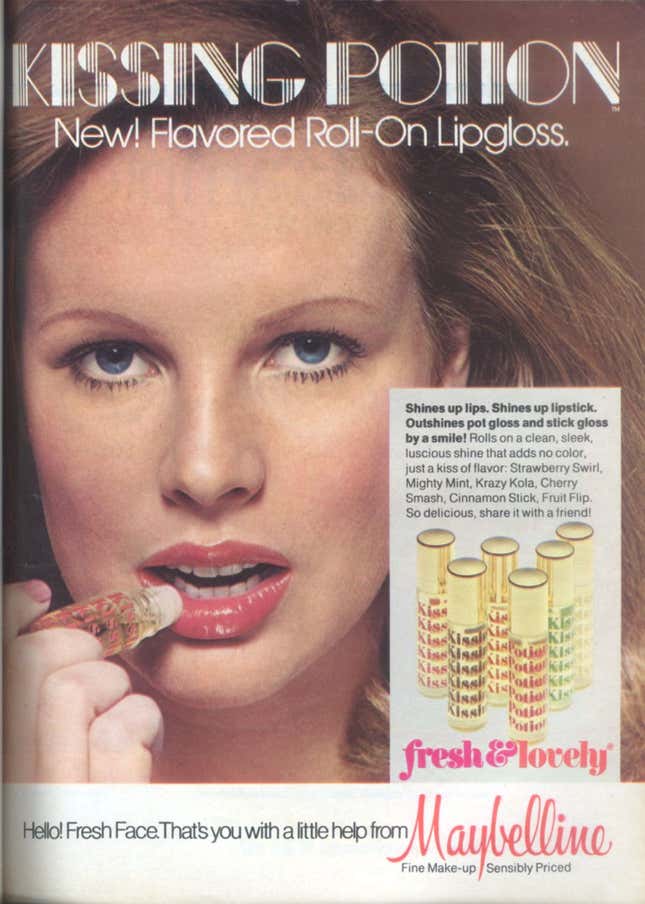

The global mythology of witches draws on the notion that women use sorcery to trick or “bewitch” men with their beauty—and the beauty industry has always used this same language to sell its products, marketing them as magical elixirs that confer beauty, youth, and sexual attractiveness.

So it’s worth asking, is the beauty industry’s current witchy vibe really tapping into witchcraft’s focus on women’s empowerment? Or is it pandering—as it always has—to a male gaze, by digging up the well-worn tropes of an ancient misogyny?

Magic yourself young

“Natural” and “clean” beauty are on the rise, and so the industry has begun to adopt the wellness mantra that one must attend to “inner and outer beauty.” Delving into mysticism and empowering witchiness has proven to be an effective way to engage customers and sell products for the “inner” part of that equation.

The beauty industry is pivoting to self-care—and a big part of that is an emphasis on skincare, instead of lipstick, mascara, or rouge. An industry forecast released by the market research firm Euromonitor (PDF) in August noted that skincare (lotions and moisturizers, serums, cleansers, toners, masks, etc.) experienced the strongest growth globally against all other cosmetics categories in the third quarter, a spot previously dominated by color cosmetics (makeup).

It sounds like good news that women are more concerned about having healthy skin than smearing it with colored pastes and powders. And it’s similarly encouraging that the language around skincare has begun to abandon militant instructions to “tackle” and “beat” blemishes or “defy” the natural aging process, and replace them with campaigns that promote products promising to “renew” or “revitalize.”

But a look inside the beauty industry’s obsession with skincare tells a less empowering story about its priorities. When it comes to retail value sales, skincare is dominated by one category: Anti-aging.

In fact it’s no exaggeration to say that “skincare” has become a euphemism for products that promise to slow, pause, or reverse aging(paywall). It’s a habit the industry can’t seem to quit: The beauty magazine Allure, for example, declared nobly that it would put the term “anti-aging” to bed once and for all, but it continues to advertise products that promise to combat the effects of age and treat youth as a proxy for beauty.

Moon Juice’s magical-sounding Beauty Dust doesn’t explicitly mention aging, but promises it “helps the body to preserve collagen protein,” and “helps enhance elasticity of the skin,” phrases that any skincare obsessive will understand as references to youthful skin. Its Beauty Shroom Plumping Jelly Serum, meanwhile, says it will “visibly reduce the appearance of fine lines and wrinkles.” Buried in the fine print of nearly all of the products from Goop’s skincare line is the language of anti-aging: its “revitalizing” day moisturizer doubles as a fine line reducer, as does its cleanser, face oil, night and eye creams. In fact, the popular wellness site’s top six skincare products all mention anti-aging in some way. It’s second-bestselling product (following a Goop exfoliating masque billed as “gateway to younger looking skin”) is a nearly $200 serum by Vintner’s Daughter, which promises a laundry list of skin improvements, but ultimately reduces fine lines and wrinkles.

“No matter how low you turn the volume, the specter of aging wails, open-mouthed and horrified, at the core of skincare,” Chelsea Summers wrote in a perceptive essay on this topic for Medium, “Aging Ghosts in the Skincare Machine.” She argued that at its core, the skincare industrial complex has always been about anti-aging, and cops to her own susceptibility, describing her costly skin routine as “an army of products I’ve marshaled with a single intent: to keep aging at bay.”

The beauty industry, in short, has replaced a profit machine preying on women’s fear of not being pretty enough with one exploiting their fear of not being young enough. Beauty is a business that has always thrived by fostering women’s insecurities, so it’s not super surprising that it’s refurbishing this trusty model for 2018, rather than replacing it.

Seen through this lens, the industry’s narrow take on mysticism doesn’t feel particularly empowering or feminist, but instead zeroes in on the same element of witchcraft the beauty industry has always referenced in its advertising language—the idea that you can “magic yourself beautiful” or “magic yourself young.”

Examples of this trope exist in fairytale and film: from Sleeping Beauty to Snow White to Game of Thrones, witchy older women are depicted as unbeautiful, resentful, and spiteful. The queen in Snow White looks at her magic mirror for an assessment of her beauty relative to young Snow White’s (perhaps an early manifestation of Instagram angst), while Game of Thrones’ seductress Melisandre is a crone who’s centuries old, but uses sorcery to disguise her age and sex to bend men to her will. The elderly witches in Neil Gaiman’s 1999 novel Stardust can reverse the aging process by eating the heart of a “Star,” who takes the form of a young woman, and Japan’s decrepit Yama Uba poses as a young woman to lure lost travelers, who she then consumes, Hansel and Gretel style.

The idea of women using sorcery to steal youth is far from harmless, as Naomi Wolf suggested in her 1991 book, The Beauty Myth: “Competition between women has been made part of the myth so that women will be divided from one another,” she wrote. “Older women fear young ones, young women fear old, and the beauty myth truncates for all the female lifespan.”

Cosmetics have always been seen as black magic

Some recent products, such as Everlasting Love, a “romance mist” sold by Goop, or Moon Juice’s Sex Dust, for $38, suggest a kind of love potion. While these things could certainly be purchased and used in an empowering and self-loving way, they also recall the idea of women as sorceresses, bent on seduction.

It’s a well-worn trope. In 1985, makeup doyenne Estée Lauder wrote of the cosmetics empire she created, “this is the story of a bewitchment. I was irrevocably bewitched by the power to create beauty.”

And indeed, if women are out to bewitch men, then makeup is the tool for this deception, and has long held a connotation of black magic and mysticism. The word “glamour” itself has roots in a Scottish term referring to magic, enchantment, and spells.

In Alexander Pope’s 1712 poem “The Rape of the Lock,” Belinda’s Instagram-worthy beauty regime is described as a religious ritual:

And now, unveil’d, the Toilet stands display’d,

Each Silver Vase in mystic Order laid.

First, rob’d in White, the Nymph intent adores

With Head uncover’d, the Cosmetic Pow’rs.

A heav’nly Image in the Glass appears,

To that she bends, to that her Eyes she rears

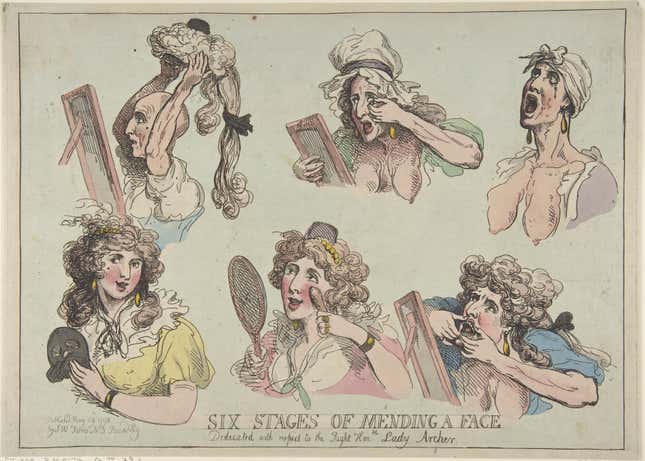

Younger women of Pope’s era were generally frowned upon for using makeup, and although it was more acceptable for older women to do so, society was predictably merciless towards them for it (not unlike the condemnation of 21st-century women who dare to get plastic surgery).

Cosmetics were thought to give women the power to dupe men with false beauty, a notion explored gleefully in Jonathan Swift’s graphic 17th century poem “A Beautiful Young Nymph Going to Bed,” which tells the tale of “Corinna, pride of Drury-Lane,” a sexy prostitute, as she removes all her cosmetics before sleep

Takes off her artificial hair:

Now, picking out a crystal eye,

She wipes it clean, and lays it by.

Her eye-brows from a mouse’s hide,

Stuck on with art on either side

The process reveals Corinna to be a hideous, aging woman, pocked by festering wounds from sexually transmitted diseases and wracked by malnutrition. The 18th-century socialite Lady Archer was cruelly caricatured in similar terms:

Corinna, Belinda, and Lady Archer, with their cosmetic deceptions, recall the succubus, a varietal of the witch in Western medieval legend, who appears in just about every culture. The succubus relies on male fears of female sexuality—generally, she has exaggerated sexual features or devil-like deformities disguised by magic—and seems to exist purely as a temptation and threat to men.

She first appears in Mesopotamian demonology as the Lilin, a night spirit that copulated with men in their sleep, and again in Arabian mythology as the qarînah. She reappears as the sexually wanton Lilith in Jewish mythology and makes her Biblical debut as Adam’s crappy first wife.

In Japanese folklore, Yuki-onna is a vampiric succubus, who feeds on mens’ blood after luring them in with sex or a kiss.

Greek and Roman mythology also loves its man-devouring witches. Circe and Calypso famously bewitched Odysseus in Homer’s The Odyssey, imprisoning him on their respective islands for years. (While Homer’s version of their histories are pretty two dimensional, Madeline Miller’s retelling of Circe’s story envisions her as the OG witch who invents witchcraft through the use of magical and herbs and healing spells). Odysseus later encounters the sirens, the witch’s aquatic sister, who lure men to their watery graves with their beauty and voices. The Siren also exists in Slavic folklore as the lake-dwelling rusalka or dziwożona, as well as the unfriendly mermaid in Western lore.

Throughout history, and even today, women have been demonized for suspected association with witchcraft. In Europe, thousands were sexually abused, tortured, and literally burned at the stake in a church-sponsored hysteria. The Salem witch trials saw 20 women similarly executed in America.

Makeup’s witchy powers were briefly prohibited in the UK via black letter law in 1770, when the British Parliament passed a ruling that condemned cosmetics due to their association with witchcraft. It stated that women who “seduced” men into marriage through the use of cosmetics like “scents, paints, cosmetic washes, artificial teeth, false hair, Spanish wool, iron stays, hoops, high-heeled shoes or bolstered hips,” could be found guilty of sorcery and face witchcraft charges.

Unsurprisingly, some fringe-y modern-day movements take a similar attitude to the use of cosmetics, most disturbingly in the incel movement, a violent political ideology created by men that centers on the injustice of young, beautiful women refusing to sleep with them.

As with these hyper-sexualized, mythological she-demons of the past, incels “tend to direct hatred at things they think they desire,” Jia Tolentino explains in the New Yorker. In this case, incels are preoccupied with female beauty but believe that makeup is a form of fraud. Many an incel Reddit-thread sees men comparing images of the same women with and without makeup, or whining that cosmetics are a lie and should be made illegal.

Even in less dark corners of the internet, the trope of witchy women using sorcery to bewitch men thrives: A less extreme example is the 2016 makeup-shaming meme, “Take a girl swimming on your first date,” which espouses the idea that one should dunk one’s date in water (witch-trial-style) to wash her makeup off and avoid being duped into dating someone they think is unattractive.

And, case in point, we have the long and varied misfortunes of the rapper and entrepreneur Kanye West, whose baffling behavior has been blamed on his wife, Kim Kardashian, and the rest of the Kardashian coven. Many have pointed to the so-called “Kardashian Curse” (a hex put on men that date a Kardashian sister) as the source of his distress, while others have joked that the family witched West into the “sunken place,” a metaphoric hell that represents the structural oppression of black people from Jordan Peele’s Get Out.

Witchy marketing isn’t endorsed by witches

The commercialization of witch culture doesn’t always work out. Goop, which is reputed to be worth $250 million, is often criticized for its white-washed variety of commercial spirituality, which it bills as “cosmic health” and accessorizes with $85 healing crystals. Meanwhile, the commodification of witch culture recently backfired on Sephora when it tried to sell a “Starter Witch Kit,” to dabblers. This managed to piss off a bunch of actual witches, and ultimately forced the kit’s manufacturer to apologize and pull the product.

Heather Greene, author of Bell, Book, and Camera, A Critical History of Witches in American Film and Television, notes over email that ”(up until recently), the witch was an example, allegorically speaking, of what a good woman should not be. More recently the character has become an expression of women’s empowerment.”

It’s fair to assume that practitioners of Wiccan, Pagan, or other spiritual faiths are not busy cooking up love potions in cauldrons or using dark arts to make themselves younger. The growth of the movement had begun before #MeToo and before Trump’s election, but has gathered steam in a climate where many women are confronting the ways they have been undermined and attacked.

“The witch as an icon is resonating right now because we’ve entered a fourth wave of feminism,” Pam Grossman, author of What Is a Witch and co-founder of the Occult Humanities Conference at New York University, told Salon in 2016. “We are redefining what power, leadership, beauty and value look like on our own terms. And the witch is the ultimate symbol of female power. Doing witchcraft is a way to connect to that energy, which is so needed right now, as we’re beginning to collectively course correct thousands of years of sexism and oppression.”

Still, the figure of the witch, as she is seen in her various iterations, is a cultural manifestation of male fears about female power, and her history does as much to expose the insecurity of men as it does the resilience of women.

Arguably, the healers, midwives, and women’s health advocates who were persecuted as witches in medieval Europe were early practitioners of wellness.

But at a time when the beauty and wellness industries are making a point of shifting their focus away from the male gaze, the witchy marketing of youth and beauty seems to be about performing for that gaze, as much as ever.