To Find the History of African American Women, Look to Their Handiwork

Our foremothers wove spiritual beliefs, cultural values, and historical knowledge into their flax, wool, silk, and cotton webs.

Rose was in existential distress that fateful winter in South Carolina in 1852. She was facing the deep kind of trouble that no one in our present time knows and that only an enslaved woman has felt. For Rose understood that, following the death of her legal owner, she or her little girl, Ashley, could be next on the auction block.

Ripping loved ones apart was a common practice in a society structured—and indeed, dependent—on the legalized captivity of people deemed inferior. And sale could not have been the end of Rose’s worries. She must have dreaded what could occur after this relocation: the physical cruelty, sexual assault, malnourishment, mental splintering, and even death that was the lot of so many young women defined as “slaves.” Rose adored her daughter and desperately sought to keep her safe. But what could safety possibly mean at a time when a girl not yet 10 years old could be lawfully caged and bartered?

Rose gathered all of her resources—material, emotional, and spiritual—and packed an emergency kit for the future. She gave that bag to Ashley, who carried it and passed it down across the generations.

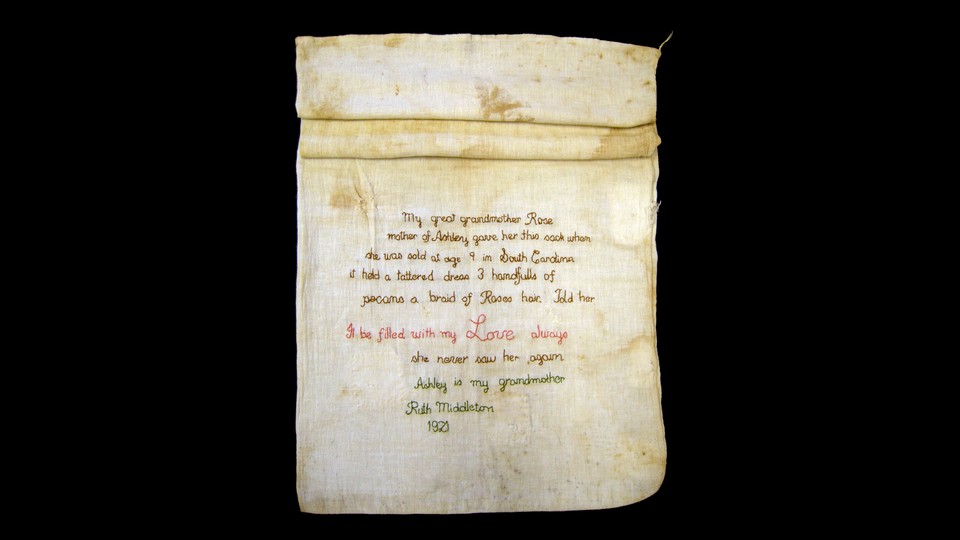

That stained antique sack hung in a case at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture, in Washington, D.C., from the day of its grand opening in September 2016 until March 2021, and the sack is now on site at the Middleton Place plantation, a national historic landmark in Charleston, South Carolina. The fabric artifact immediately takes hold of those who view it, for on the cotton sack is embroidered an inscription that appears to us like a message in a bottle from across the waves of time:

My great grandmother Rose

mother of Ashley gave her this sack when

she was sold at age 9 in South Carolina

it held a tattered dress 3 handfulls of

pecans a braid of Roses hair. Told her

It be filled with my Love always

she never saw her again

Ashley is my grandmother

Ruth Middleton

1921

The study of the history of African American women is particularly challenging because the keepers of records often overlooked us. The historian Jill Lepore has encapsulated the problem in relation to the wide scope of American history, writing that the “archive of the past … is maddeningly uneven, asymmetrical, and unfair.” So where can historians turn when the archival ground collapses beneath us? To discover the past lives of those for whom the historical record is abysmally thin, I’ve found that we must expand the materials we use as sources of information.

Though early women’s history can be elusive, women need not “conjure a history for ourselves,” the archaeologist Elizabeth Wayland Barber says. “Here among the textiles,” she writes, “we can find some of the hard evidence we need.” The historian Elsa Barkley Brown wrote that if we “follow the cultural guides which African American women have left us,” we will “understand their worlds.” Our foremothers wove spiritual beliefs, cultural values, and historical knowledge into their flax, wool, silk, and cotton webs. The work of their hands can lead us back to their histories, and serve as guide rails as we grope through the difficult past.

Many of us feel connected to history through women’s handiwork. Some save and repair hand-me-down table linens. Others hunt flea-market aisles for vintage fabrics. A few of us learn the skills of traditional sewing and quilting to reproduce the experience and art of our foremothers. The past seems to reach out to us through these fabrics and the practices of making them that have survived over time. Gathered up like the crisp ends of a cotton sheet fresh from the wash, past and present seem to meet above the fold.

Ashley’s sack is an extraordinary artifact of the cultural and craft productions of African American women. But it is not just an artifact. It is an archive of its own, a collection of disparate materials and messages, at once a container, carrier, textile, art piece, and record of past events. The lives of three ordinary African American women—Rose, Ashley, and Ruth—spanned the 19th and 20th centuries, slavery and freedom, the South and the North. Their love story as told through this sack is one of sacrifice, suffering, lament, and the rescue of a tested but resilient family lineage.

Rose exemplifies the collective experience of enslaved Black women, who preserved life when hope seemed lost. Rose’s kit was, by all evidence, one of a kind, but she shared with other women in her condition a vision for survival that required both material and emotional resources. She sought to immediately address a hierarchy of needs: food, clothing, shelter, identity through lineage, and, most centrally, an affirmation of worthiness. Rose gathered a dress, nuts, a lock of hair, and the cotton tote itself—things shaped by the intermingling of southern nature and culture. These items show us what women in bondage deemed essential, what they were capable of getting their hands on, and what they were determined to salvage. Rose then sealed those items, rendering them sacred, with the force of an emotional promise: a mother’s enduring love.

Despite mother and daughter’s separation, the bond between them held longevity and elasticity, traversing the final decade of chattel slavery, the chaos of the Civil War, and the red dawn of emancipation before finding new expression in the early 20th century, as a baby girl, Ruth, Ashley’s granddaughter, was born.

Just as remarkable as this story is how we have come to know about it. Through her embroidery, Ruth ensured that the valiance of discounted women would be recalled and embraced as a treasured inheritance.

A granddaughter, mother, sewer, and storyteller imbued a piece of old cloth with all the drama and pathos of ancient tapestries depicting the deeds of queens and goddesses. She preserved the memory of her foremothers and also venerated these women, shaping their image for the next generations. Without Ruth, there would be no record. Without her record, there would be no history.

Aptly called a “revelation” by Jeff Neale, a museum interpreter at the Middleton Place plantation, Ashley’s sack illuminates the contours of enslaved Black women’s experiences, the emotional imperatives of their existences, the things they required to survive, and what they valued enough to pass down. “The things we interact with are an inescapable part of who we are,” as the historian of the environment Timothy LeCain has put it, and hence things become our “fellow travelers” in this life.

Every turn in the sack’s use—from its packing in the 1850s to its tending across the dawn of a century to its embroidering in the 1920s—reveals a family endowment that stands as an alternative to the callous capitalism bred in slavery. As the women in Rose’s lineage carried the sack through the decades, the sack itself bore memories of bondage and bravery, genius and generosity, longevity and love.

This textile has an effect subtler yet more moving than that of any monument. Ashley’s sack is a quiet assertion of the right to life, liberty, and beauty even for those at the bottom, and stands in eloquent defense of the country’s ideals by indicting its failures.

This post is excerpted from Tiya Miles’s book All That She Carried: The Journey Of Ashley's Sack, A Black Family Keepsake.