“Plant blindness” is a modern phenomenon describing people’s inability to readily identify the species of plants they live among every day. It causes a lot of hand-wringing in the botany community. If people are blind to plants, they’re probably less invested in, say, saving them from extinction.

Not that long ago, the threat to certain plants wasn’t neglect—it was way too much affection. From the 1850s to the 1890s, ferns began appearing on everything from pottery to gravestones in Victorian England, and fern collecting became all the rage, particularly among women. “They were totally obsessed,” says Nathalie Nagalingum, the chair of botany at the California Academy of Sciences.

“Of all the many passions and crazes in 19th-century gardening and natural history, none was as long lasting or as wide reaching as fern fever,” wrote Sarah Whittingham in Fern Fever: The Story of Pteridomania. “If you decorated and furnished your house, went to the seaside, strolled in pleasure gardens, patronized the theatre and concerts, visited exhibitions, read novels, played music, or spent time in hospital, you encountered ferns and ferneries.”

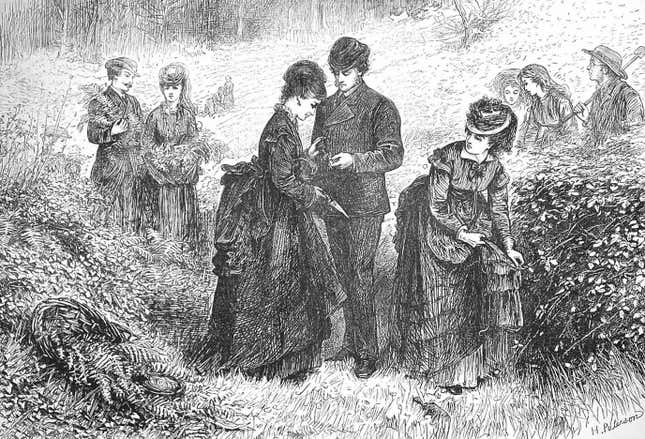

For women, the social significance of the moment transcended mere trendiness. Collecting ferns was a rare activity male-dominated (and chaperone-obsessed) Victorian society permitted women to do on their own.

However, as such, it was soon derided as a sort of affliction. Charles Kingsley, a Victorian-era novelist, termed the obsession the faintly pathological “pteridomania” (ferns belong to the group of plants known as pteridophytes). Victorians loved to diagnose madness in any irregular behavior, and it was often deeply gendered. That extended to pteridomania, writes Nora Mueller at Garden Collage. Once women got involved, it became a “mania.” Mueller writes:

This propensity often targeted women specifically (the most obvious example being hysteria); it comes as little surprise that the first naming of pteridomania came in response to the interest young women took in the activity of fern hunting. In [his book]Glaucus, or, the Wonders of the Shore, Charles Kingsley wrote, “Your daughters, perhaps, have been seized with the prevailing ‘Pteridomania’…wrangling over unpronounceable names of species (which seem different in each new Fern-book that they buy).”

Kinglsey wrote that it was a healthier preoccupation for young women than “novels and gossip,” and Charles Dickens suggested that his daughter care for ferns to cure her of her perceived apathy, according to Atlas Obscura.

All this fern collecting took a toll on the native populations of the plants. Whole hillsides were denuded of them, particularly in Scotland and Ireland. The effects on fern species are still felt today; the threatened Killarney fern, for example, is still “restricted in their distribution,” meaning there are fewer of them than there should be, according to the Irish National Parks & Wildlife Service:

A lack of suitable continuous habitat and the effects of historic depredation of the sporophyte generation during the “Victorian Fern Craze”, also known as “Pteridomania”, which was at its height in the 1850s–1890s…may explain the distribution of this species in Ireland.

Indeed, it is possible to love something to death.