On Dec. 11, the Wall Street Journal published an op-ed by Joseph Epstein claiming that Jill Biden’s use of the title “Dr.” feels “fraudulent, even comic,” and referring to her as “kiddo.” The tone of the piece is all too familiar to women, especially Black and brown women, across academia, who know what it feels like to be constantly questioned about their expertise from peers and strangers alike. The article led to an uproar, with academics across disciplines calling out its sexism and snobbery. Responses in the Atlantic, the New York Times, Forbes, and elsewhere argued that Biden should ignore Epstein’s advice to “consider stowing” her degree and stick to her honorific.

Academia is no stranger to overt and subtle sexism, which can manifest through student evaluations or even how women academics are introduced during speaking engagements. The field of economics, of which we are both a part, has been publicly grappling with sexual harassment claims and discrimination toward women. This was highlighted in 2018 by the work of Harvard economics Ph.D. student Alice Wu, who trained a machine-learning model on text to reveal gender bias in how women in economics are talked about on an anonymous forum.

Using a simple version of Wu’s method, we evaluated the 3,771 comments (as of noon on Monday) on Epstein’s op-ed on the Wall Street Journal website. Commenting there requires an account with a first and last name, and we proxy for individuals’ gender using their first names. (We acknowledge that gender is not binary, and that using names as a proxy is an imperfect measure, since one can’t always determine someone’s gender from their name alone.)

While our findings may not reveal exactly what the editors were thinking when they allowed the op-ed to run—comments sections are, obviously, their own special universes—they do show that the men and women who were moved to respond to Epstein’s piece saw two very different op-eds.

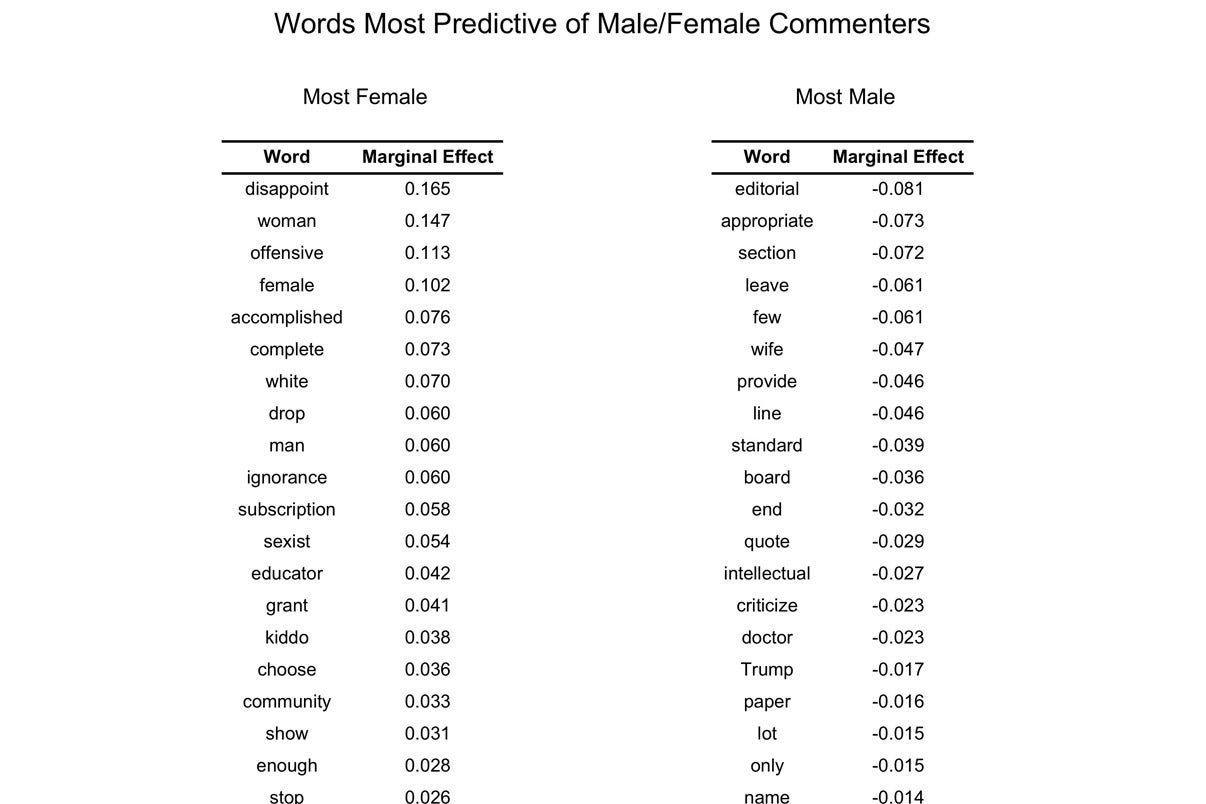

Our basic machine-learning technique finds the words most predictive of whether a particular comment author is a man or a woman. The marginal effects (below) tell us about the likelihood of a poster’s gender given that they use a particular word: Words with marginal effects closer to 1 are predictive of female commenters, and those with marginal effects closer to -1 are predictive of male commenters. (You can find our code here.)

The breakdown shows female commenters were more likely to identify sexism and misogyny in the article as compared with male commenters. Among the words most predictive of a female commenter are woman, female, and sexist, terms explicitly related to gender, and

disappoint, offensive, and kiddo, suggestive of much stronger distaste and dissatisfaction. The most predictive words of male commenters are editorial, appropriate, and section—all indicative of a much less strong reaction. Interestingly, men were also more likely to use the words wife and Trump.

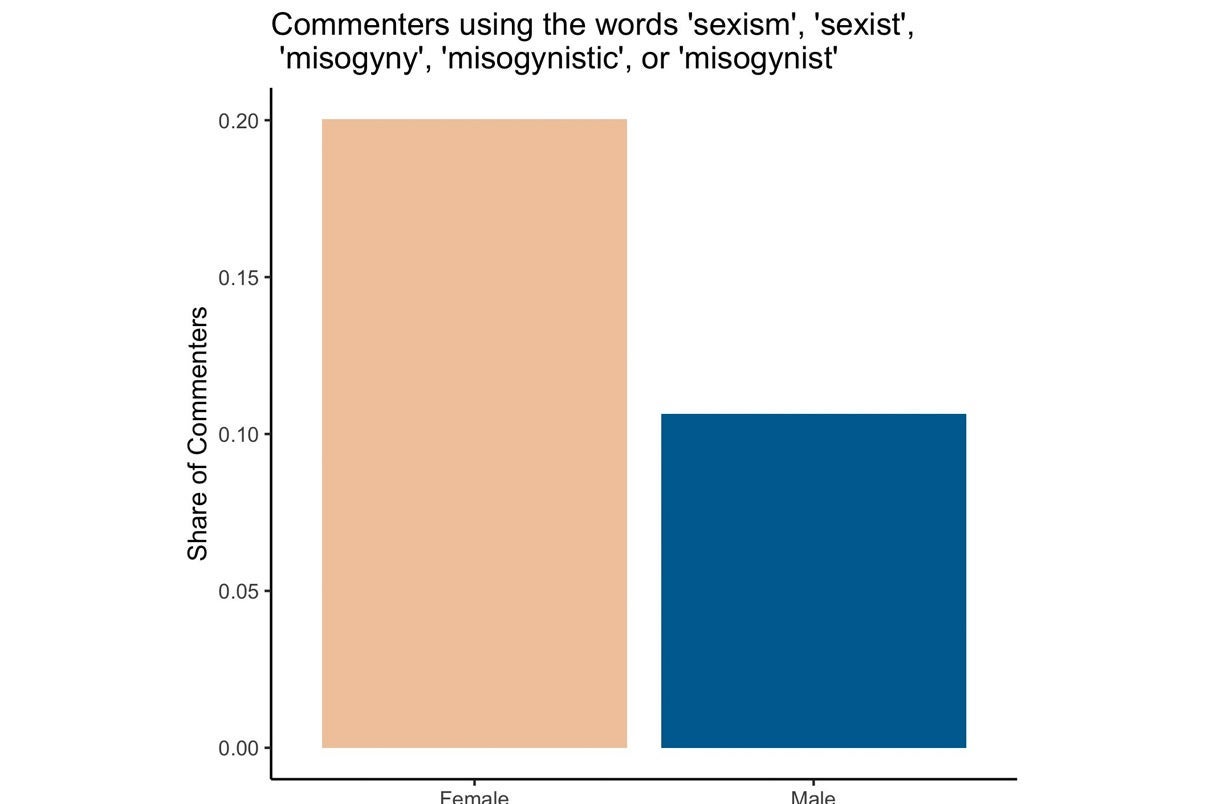

OK, so what does this tell us? Male readers, even if they disagreed with Epstein’s opinion, often didn’t interpret it as inherently sexist, instead focusing on other aspects of the piece. In fact, women were nearly twice as likely as men to respond to the article with comments that explicitly used the terms sexism or misogyny. Male editors might have interpreted the article similarly to male readers—seeing only an individual airing his thoughts, business as usual. (The two top editors of the Wall Street Journal’s opinion section are white men, including the section head who has publicly defended the decision to run the op-ed.)

But business as usual, especially in academia, manifests as gender discrimination and sexual harassment, creating uniquely toxic workplaces for women who choose to pursue doctorates in their disciplines. Business as usual also allows women to be generally viewed as less competent than men even when considering status and expertise.

What happened to Jill Biden—being told, essentially, to know her place—is not uncommon. Women continue to face barriers in academia despite efforts to achieve equity and recognition. Not every Ph.D. or Ed.D. uses the honorific “Dr.,” but the steep climb of attaining those degrees at the very least earns them the right to call themselves whatever they want without someone making assumptions about their qualifications or expertise. Why did the Wall Street Journal’s opinion section downplay Biden’s credibility as a scholar? It may have been, in part, because its editors did not even see the article’s sexism—even though, from the word kiddo onward, that sexism stared readers right in the face.

Biden’s defiance of cultural and professional expectations for women is a significant moment in history. In her choosing to be unapologetically herself as an educator, practitioner, mother, wife, grandmother, and now first lady, she is showing women that they can occupy whatever space they choose as their full selves. That matters for everyone—even those who read the op-ed and only saw business as usual.