Why We Need to Start Building Monuments to Groundbreaking Women

The brilliant female codebreakers of WWII were forgotten to history, but would that have happened had they been recognized with the same fervor as men?

/https://tf-cmsv2-smithsonianmag-media.s3.amazonaws.com/filer/b4/85/b485646f-4dbb-4448-83a3-064df401a8e6/c6790b.jpg)

A few years ago, residents of a Washington, D.C., neighborhood decided to spruce up the old wrought-iron fire-department call boxes that dotted their sidewalks, part of a city-wide effort to beautify and restore these elegant (if no longer used) curiosities. They painted the poles a deep blue with gold trim, then commissioned local artists to add scenes to the call boxes, depicting the area's past. Residents knew their sector of the city harbored a proud secret, one that I write about in my recent book Code Girls: During World War II, some 4,000 women codebreakers toiled in a top-secret compound on the grounds of a former girls’ school, breaking codes and ciphers used by deadly Nazi U-boats and the Japanese Navy. To honor these women, the neighbors arranged for the portrait of a female code breaker to be painted on one call-box cabinet—for a model, they chose Alvina Schwab Pettigrew of South Dakota--and put a small plaque on the other side explaining what she and her colleagues did.

The call box has a homespun quality and remains easy to miss, located on a busy avenue, near a bus stop. But to date it represents the only public effort to honor the 11,000 women whose collective work helped win World War II.

Now, 75 years later, it’s time for them to get more than a call box. Historians today accept that code breaking shortened the war by at least a year, and saved thousands of lives on battlegrounds and at sea. In the United States—which had an even larger code-breaking operation than Britain’s famous Bletchley Park—more than half of the code-breakers were women. In addition to the thousands of women at the D.C. facility, which was run by the Navy, another 7,000 broke codes at an Army compound across the river in Arlington, Virginia.

The penalty for talking about their work was death. The women were told they’d be shot if they blabbed. If anybody asked what they did, they were to say they were secretaries, sharpening pencils and emptying trash cans. Because they were women, people readily believed the work they did must be unimportant. Yet it’s no exaggeration to say that these women helped build the modern intelligence community, pioneering the field of cyber-intelligence, and ran code-breaking machines that were forerunners of modern computers.

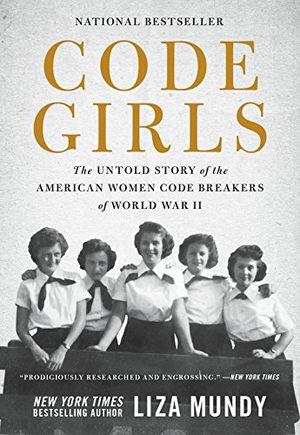

Code Girls: The Untold Story of the American Women Code Breakers of World War II

A strict vow of secrecy nearly erased their efforts from history; now, through dazzling research and interviews with surviving code girls, bestselling author Liza Mundy brings to life this riveting and vital story of American courage, service, and scientific accomplishment.

March is Women's History Month. This year it comes at a time when the twin forces of the debate over Confederate memorials and the #metoo movement have created an upswing in public interest about how and who we memorialize. Changes are being made. In New Haven, Connecticut, Yale University removed the name of white supremacist John C. Calhoun from a residential college and replaced it with that of Rear Admiral Grace Murray Hopper, the brilliant Vassar math professor who helped develop the Navy’s early computers and pioneered the first programming language.

In Salt Lake City, an elementary school named for President Andrew Jackson has been re-named for Mary Jackson, NASA’s first black female engineer. In Richmond, Virginia, a statue of Maggie L. Walker, an African-American businesswoman and the first U.S. woman to charter a bank, provides a much-needed counterpoint to the statues of Confederate generals lining Monument Avenue. In New York, officials have agreed to relocate the Central Park statue depicting J. Marion Sims, a white doctor who performed experimental gynecological surgery on black slave women without true consent or anesthesia, and to add plaques explaining just what his legacy entailed. Also in Central Park, where historically there have been no statues representing real historical women (fictional figures, like Alice from Alice in Wonderland, have statues), advocates have succeeded in winning a monument to Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and other suffragettes. =

But it’s extraordinary, the extent to which our public art still over-tells the story of men’s contributions at the expense of women’s. In all of Washington, D.C.—a city where it would seem that no male military officer or government leader has been denied a spot in some square or traffic circle—there are only a handful of statues depicting historical women: Joan of Arc, educator Mary McLeod Bethune, Eleanor Roosevelt, among a few others. The other 50-odd female (or female-ish) statues mostly depict abstract concepts like grief or freedom, or else they are anonymous forms arrayed in worshipful poses around men, fulfilling the hallowed female role of gazing adoringly upon men and encouraging homage to them, all the while remaining, themselves, unnamed.

Too often public art still does to women what history has done; it minimizes their achievements and denies their full humanity. When researching my book, I was astonished at how many histories and memoirs of the code-breaking triumphs of World War II—the breaking of the Nazi Enigma cipher, the ingenious code-breaking that led to Pacific victories such as the Battle of Midway—overlooked the major role that women played.

It took a declassified history by the National Security Agency to provide the initial inkling of the full story, which then led me to the hundreds of files about code-breaking efforts at the National Archives that contained rosters of women’s names and records of what they did, declassified and available for decades. The evidence was there, in records sifted through by many historians, who, it seems, had not thought the women worthy of much mention.

The nation’s capital has long been a magnet for female talent. The Civil War and every conflict thereafter drew women seeking jobs with the growing federal government at a time when men were unavailable to fill those roles. In World War II, tens of thousands of women boarded trains to come work for agencies such as the FBI, the Office of Strategic Services, and the Pentagon. The women code-breakers were mostly young college graduates and ex-schoolteachers, adept in math and languages, who found themselves working ‘round the clock shifts, breaking complex enemy systems. Known as government girls, or g-girls, they changed the city’s landscape; many apartments were built to house them, and a number still exist. And yet there is little, apart from that call box, to celebrate what they did.

Apart from the everyday women who broke new ground in the field of cryptanalysis, there are a few women whose absence from our nation’s historical memory is even more egregious. During the 1920s and 1930s, a former Texas schoolteacher and mathematical genius, Agnes Meyer Driscoll, labored in obscurity in the small (at the time) codebreaking bureau of the US Navy, where she, as a civilian, diagnosed how the Japanese Navy enciphered its fleet code. She taught the male naval officers who broke enemy codes that led to victory in the Battle of Midway--and her name should be emblazoned on a building, a battleship, or both. To date, pretty much all she has gotten is a roadside marker near her childhood home in Ohio.

Elizebeth Friedman, a former schoolteacher, decoded the messages of rum-runners, as well as other smugglers, during and after Prohibition. There is an auditorium dedicated to Friedman in the headquarters of the bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives—just as, inside NSA headquarters, the director’s conference room is named for Ann Caracristi, a World War II code breaker who rose to become the agency’s first female deputy director. Such spaces are well-earned tributes, but the public still knows little about these women.

At Arlington Hall, the Army’s wartime codebreaking compound, now used as a training center for foreign service officers, there is little, if anything, to herald the 7,000 women who labored there during the war. The National Cryptologic Museum, adjacent to the NSA headquarters in Maryland has an exhibit on cryptanalytic women, but it's off the beaten path.

There are many reasons to commemorate these women. For one thing, they should be thanked for their service. Their descendants—many of whom work in intelligence—deserve a place to visit and meditate on what their mothers, aunts and grandmothers did. And as modern women fight, even today, for full inclusion in sectors like technology and military service, it’s essential to fill out the historical record and show that women have been in those sectors all along; that women helped pioneer them.

The idea is not to topple extant statues. It’s to augment them with monuments that tell the full story of American history. And even though its also rare to find a statue of a male cryptanalyst, there are plenty of World War II soldiers valorized for their bravery with a monument. A proper memorial for the “Code Girls” might show the women working at tables surrounded by towering stacks of Japanese messages; or standing at huge machines cracking German U-boat ciphers, keeping Allied convoys safe as they crossed the Atlantic.

Recently, I was fortunate to be on a panel with Margot Lee Shetterly, author of Hidden Figures, the book (and movie) that tells the story of the African-American women mathematicians who powered the space race. She pointed out that there have been always been women shaping American history, but it’s as though they were laboring in darkened rooms. Now, the light switches are being flipped and we can see that women have been there, in surprising numbers, all along. Their achievements only need to be illuminated to be seen.

A Note to our Readers

Smithsonian magazine participates in affiliate link advertising programs. If you purchase an item through these links, we receive a commission.