During the first act of Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton, Aaron Burr remembers his mother, the late Esther Edwards Burr, with intense, almost apotheotic fondness:

“My mother was a genius

My father commanded respect.

When they died they left no instructions.

Just a legacy to protect.”

In a world where women were seldom regarded for their intelligence (and in a musical where women are celebrated yet largely defined by their relationships to men), the word “genius” pierces through the song like a clue to be solved. Who exactly was Esther Burr? it compels us to ask. And how did she seemingly leave her son with such a life-altering inferiority complex?

In February 1732, Esther was born just as her father, the theologian Jonathan Edwards, was preparing to lead one of the greatest evangelical revivals of the First Great Awakening. Growing up in Northampton, Mass., she witnessed thousands of “unconverted” souls flock to her father’s church, where he sermonized on the need for repentance and God’s power to “cast wicked men into hell.”

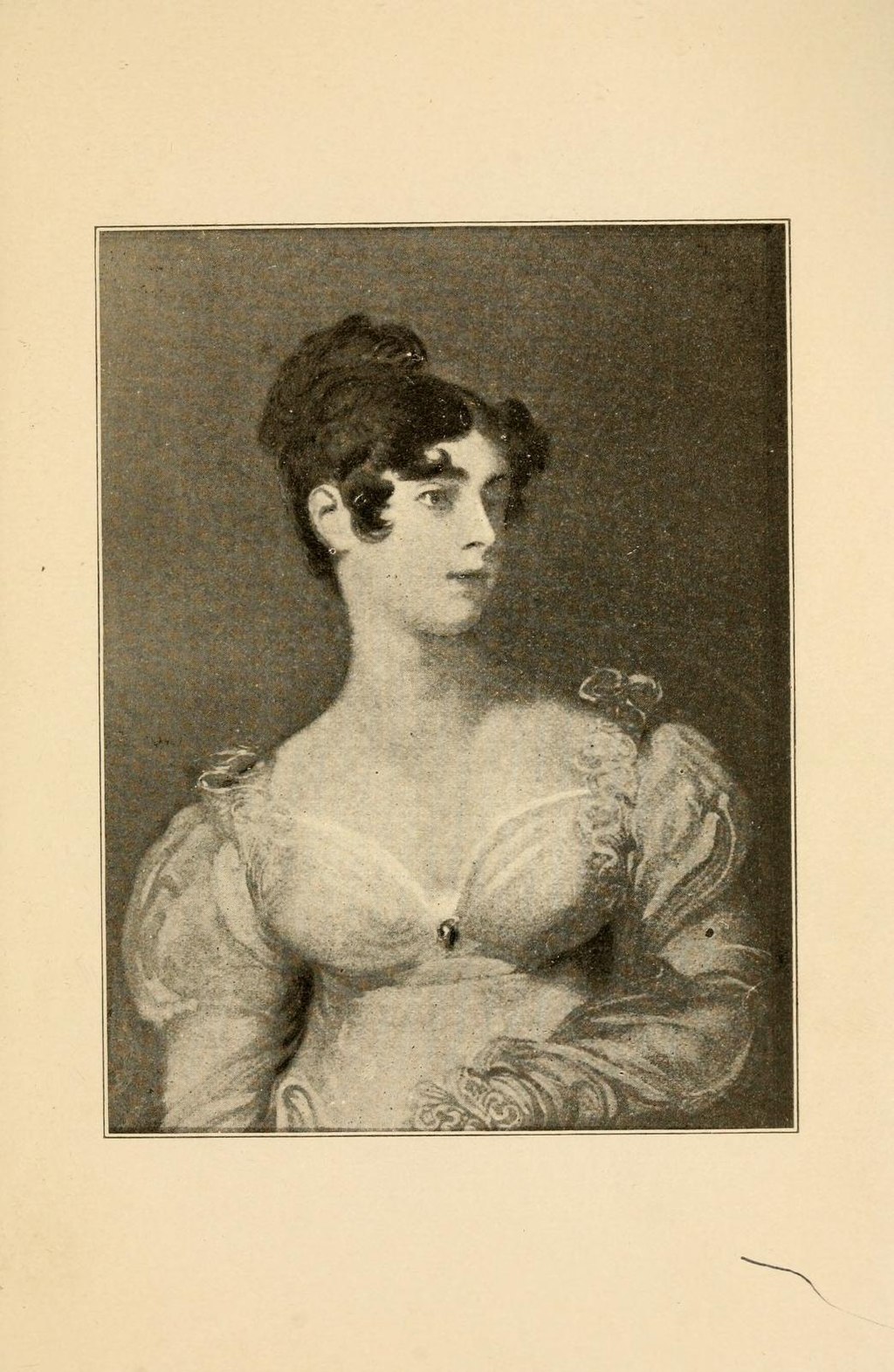

As the third of Edwards’s 11 children, Esther was hailed as a “great beauty”—the so-called “flower of her family”—though her allure extended well beyond the cosmetic. According to Samuel Hopkins, a frequent visitor to the Edwards parsonage (and Jonathan Edwards’s future biographer), she was not only an engaging conversationalist who “knew how to be facetious and sportive,” but also a highly intelligent woman who possessed a “sprightly imagination” and “an uncommon degree of wit.”

Raised by his erudite mother and four older sisters, Jonathan Edwards treated Esther very much as a pupil, as did her forward-thinking husband, Aaron Burr, Sr., whom she married in 1752 at the age of 20. Yet even so, Esther’s schooling only went so far. Per Calvinist doctrine, Edwards prioritized Esther’s education primarily as a means to save her soul, believing all children to be “heirs of hell” who must be “born again” through endless introspection and self-castigation. And while he and Burr, Sr., each conceded that men and women were spiritually equal before God, they worked hard to ensure that this idea never invaded their social and familial relationships, for fear that—in the words of the Reverend John Adams—“too learned Females [would] lose their Sex.”

As inheritors of this patriarchal order, historians today are left with few records of the female colonial experience. A striking exception is Esther Burr’s 300-page journal—considered to be the earliest continual record of female life in colonial America. Composed as a series of letters sent to Esther’s closest friend, Sarah Prince, between 1754 and 1757, the journal is naturally quotidian, featuring commentary on domestic labors and tasks, though it also suggests real frustration with women’s place in society. Struggling to find “one vacant moment,” Esther describes her experience with early motherhood as isolating, constrictive, and even claustrophobic: “When I had but one Child my hands were tied,” she wrote after the birth of Aaron Burr, Jr., in 1756, “but now I am tied hand and foot. (How I shall get along when I have got ½ dzn. or 10 Children I cant devise.).”

Read more: Forget Hamilton, Burr Is the Real Hero

Adding to the challenges posed by raising the young Aaron, whom Esther called “mischievous” and “sly,” was the sense that her home was a sort of “solitary” prison. Yet in important ways, this confinement was also freeing. Sequestered from the male gaze, Esther’s letters to Sarah allowed her to participate in an organic exchange about God, politics, literature, and war, thus liberating what she called her “other self” from the person she was conditioned to be.

Of course, such freedom did not come without doubt or apprehension. Writing to Sarah, Esther often expressed fear of male discovery. Having internalized her father’s puritanism, she also voiced guilt over the intensity with which she wrote and felt, indicting herself as “worldly minded” and thus “unfit” to “ap[p]roach the Lord’s Table.”

Nevertheless, Esther persisted writing until her sudden death at the age of 26. From start to finish, her letters track her empowerment as she engages in “free discourse” with her father and even speculates whether women should assume control of the colonies. In one of her last letters to Sarah, she delivers perhaps her most powerful defense of her sex, recounting a conversation with a male acquaintance, who argued that friendship – then considered to be the highest form of intellectual expression – was only possible for men: “I retorted several severe things upon him before he had time to speak again. He Blushed and seemed confused…[and] I talked him quite silent.”

Nearly three centuries after Esther’s death, her journal endures as an indispensable historical document. In addition to foreshadowing the emergence of a literary genre centered on private work (i.e., the poems of Emily Dickinson), it positions Esther as an author in her own right. Inspired by Samuel Richardson’s epistolary novels Virtue Rewarded (1740) and Clarissa (1748), Sarah and Esther (whom Sarah affectionately called “Burrissa”) numbered, copied, and saved each of their letters, all with the intention of creating their own narrative—and cementing their own interpretation–of life in the Atlantic world. While they would never have sought to publish, their letters allowed them to participate in the male “spheres” of authorship and friendship, affording them the space to register their experiences and validate their perspectives.

Read more: 9 Women From American History You Should Know, According to Historians

In their introduction to the 1984 edition of Esther’s journal, Carol Karlsen and Laurie Crumpacker underscore the role Esther’s faith played in this validation, framing it as “at once a cause of her oppression, an obstacle to overcoming it, and a source of strength under it.” Anticipating modern feminist theology, Esther was able to redefine her friendship with Sarah—as well as the writing that helped it flourish—as a form of divine “communion,” so much so that she believed it “aught to be a matter of Solemn Prayer.” “Inkindled” by this “spark from Heaven,” she thus wrote not only to interrogate the patriarchal order, but also to nurture a more empowered self.

Yet even so, Esther’s identity as a “feminist” remains less predictive than realized. “You’ll notice that we did not use the word ‘feminist’ in our introduction,” Karlsen, now a professor emeritus at the University of Michigan, tells TIME. “There were certainly ‘feminist impulses’ [in Esther’s journal],” she adds, “but we were hesitant to use the word, so we relied on this idea of ‘imminent feminism’ instead.”

Much like the way mainstream feminism has historically emphasized the experiences of white women, the “imminent feminism” reflected in Esther’s journal also bears a dark stain in its exclusion (and exploitation) of Black and native people. Certainly, Esther’s assumed complicity with her husband’s purchase of a slave in 1756 makes her a perpetrator of the white patriarchal hegemony that undergirded slavery as much as she was a victim herself.

Years after Esther’s death, then-senator Aaron Burr, Jr. would call for an immediate end to slavery while prioritizing (albeit privately) the education of his own wife and daughter. “Be assured,” he wrote to his wife Theodosia after reading Mary Wollstonecraft’s A Vindication of the Rights of Woman (1792), “that your sex has in her an able advocate. It is, in my opinion, a work of genius.”

Get your history fix in one place: sign up for the weekly TIME History newsletter

We cannot view Aaron Burr’s call for emancipation as an atonement of his parents’ sins, nor can we necessarily infer a direct link between Esther’s influence and Burr’s support of women. Yet in Burr’s life and career, we can see echoes of Esther’s precocity, resolve, and sense of “peculiar” destiny. As the musical Hamilton suggests, her legacy haunted him wherever he went.

After the American Revolution, it was written that “American literature boasts so few productions from the pens of ladies.” Even today, the writing of women like Esther—together with that of Phillis Wheatley, Mercy Otis Warren, and Judith Sargent Murray—remains largely unacknowledged, perpetuating the idea of women as passive victims whose stories don’t need to be told.

But as Esther’s writing, life, and legacy show, colonial women were more powerful than we give them credit for. Through their daily (and often secret) labors and discoveries, they chipped away at patriarchal authority, gaining control over their destinies as well as those of others. And while their stories may have been ignored when they wrote them, they demand to be read today.

More Must-Reads From TIME

- The 100 Most Influential People of 2024

- The Revolution of Yulia Navalnaya

- 6 Compliments That Land Every Time

- What's the Deal With the Bitcoin Halving?

- If You're Dating Right Now , You're Brave: Column

- The AI That Could Heal a Divided Internet

- Fallout Is a Brilliant Model for the Future of Video Game Adaptations

- Want Weekly Recs on What to Watch, Read, and More? Sign Up for Worth Your Time

Contact us at letters@time.com