Wouldn't It Be Nice to Have a Woman's Shoe Emoji That Isn't a Red Stiletto?

Florie Hutchinson thought so. So she set to work creating a new one.

Emojitracker is, in theory, a database that tracks the emojis people use, in real time, on Twitter. Emojitracker is in practice, however, even more than an offering of information, a work of art. Spanning 10 columns across, and many, many rows down, the site dynamically sorts the pictograms that have thus far been standardized into the digital lexicon: As people publish emojis, at a general rate of hundreds every second, the boxes containing the emojis flash. The usage tallies printed next to the emojis flutter. The effect is mesmerizing. On Emojitracker, the joy-teared face twinkles. So does, just below it, the face twisted in agony. And the party hat, and the pizza, and the cat with the heart eyes, and the heart on its own, and the heart that is broken: There they are, all together, shimmering at the touch of distant fingers, filling the spaces where words are too much or not quite enough.

At the moment, there are 2,666 emojis in the Unicode Standard, additions to the original 176 that were designed by Shigetaka Kurita, on behalf of the Japanese telecom NTT DoCoMo, in the late 1990s. The pictograms he chose for that purpose were generally intended to be lighthearted—food, sports, a rocket ship, the stuff of lols and whimsy—and they were quickly adopted, in Japan and beyond, as colorfully cheeky augmentations to text of black and white. Over the nearly 20 years of emojis’ existence, though—as with so many other things in the digital world—the dynamics of scale have taken what was once merely playful and made it immensely powerful. The more regularly we far-flung humans are using emojis as an extension of verbal language—the more the boxes of Emojitracker shimmer and shine—the more these cartoonish pictographs will adopt a responsibility: to reflect life as people actually live it, and to represent people in all their weird and magical complexity.

That’s not just a cultural challenge, but a logistical one. A new word can be coined by anyone; for an emoji to be added to the lexicon, though, it must be approved by the Unicode Consortium, the Mountain View–based nonprofit that is generally charged with standardizing characters across platforms—making sure, basically, that when you send a character from your iPhone, your Samsung-using friend will receive the same character on the other end. The Unicode Consortium, though, is more popularly known as the body that approves the emojis that go on to shape human communication, one glistening pictogram at a time. This is the story of how one such emoji—a simple flat shoe, for women—has attempted to join the ranks.

The problem became clear, as so many will, in the middle of the night. Florie Hutchinson was up in the in-between hours nursing her third daughter—Beatrice had been born in November of 2016, on the evening of the presidential election—and was texting a friend. Hutchinson happened, in the course of a message, to type the word shoe. In her phone’s suggestions field, a stiletto, fire-engine red, popped up. Hutchinson balked. “I just stared deliriously at the auto-populated emoji on my phone,” she told me. She began asking friends: What came up for them when they typed “shoe” into their smartphone keyboards? The answer, for women and men alike, came back: a stiletto, red in color and teetering in height, bold in aesthetic but stealthy in its implications and assumptions. Again and again, it was 👠 and 👠 and 👠 .

Hutchinson, as a public-relations specialist focused on the arts—and as someone based in Palo Alto, and thus immersed in Silicon Valley’s tech-saturated culture—and also, for that matter, as a mother of three young girls—was struck by the messages the emoji keyboard was sending, to her and to people around the world. She began researching: about emojis, about heels, about the series of events that had led the simple word shoe to map to one of that concept’s least simple manifestations. “Yes, I’m a feminist,” Hutchinson says, “but it’s not that I think that the emoji gods have decided to unilaterally make this a patriarchal structure that blah blah blah blah blah. I just think it’s one of those things that, at the time, to whoever designed it, it seemed like a sensible thing that women would immediately gravitate to. But with a bit of hindsight, you realize that this is systematic—and symptomatic of a greater problem.”

For Hutchinson, that problem wasn’t the existence of 👠 on the emoji keyboard (“I love the creative beauty that comes with a highly conceived and designed high-heeled shoe,” she notes). The problem instead was the 👠 used as her emoji keyboard’s default “shoe.” And, even barring that—following a recent iOS update, shoe now maps first to the Man’s Shoe 👞 , which is unsatisfying for its own obvious reasons—the problem was also the fact that, according to the logic of the emoji keyboard, women walk the world in heels. On that keyboard, Hutchinson realized, of the four shoes that are traditionally associated with women, three of them have heels: There’s a heeled boot, tan in color 👢 ; a heeled mule, open of toe and chunky of sole 👡 ; and then, yes, that ubiquitously red high heel. (The fourth is a unisex running shoe: 👟 .)

And heels, as symbols and as objects, are fraught. They are impractical—that is their menace as well as their appeal—and, because of that, they are typically associated not just with feminine beauty, but also with feminine hindrance: with frivolity, with danger, with the ability to bear pain. The pictographs Emojipedia offers as related to the “High-Heeled Shoe” include “Bride With Veil 👰 ,” “Department Store 🏬 ,” and “Lipstick 💄 .” And the entry for “Man’s Shoe” explains itself like so: “Unlike womens [sic] shoes, this shoe is likely to be comfortable.” The encyclopedia, in this assessment, is of course revealing as much about a gendered world as it is about lace-up Oxfords.

Hutchinson researched some more, and she discovered that the Unicode Consortium accepts proposals for new emojis from members of the public: Create a design, explain why your emoji should exist, and, after a review process, get a vote. If your emoji is approved, it will be coded into the operating systems of Apple and Google, Facebook and Twitter, Samsung and Microsoft and LG and on and on—living in phones and screens around the world. From there, Hutchinson decided that she would submit her own emoji proposal, for footwear that is both practical and feminine. She would request that the emoji keyboard include a woman’s flat shoe: simple, elegant, and reflective of the world women walk.

To start, Hutchinson got in touch with Jennifer 8. Lee, one of the creators, with Yiying Lu, of the recently added dumpling—an emoji brought to life with the help of a popular Kickstarter—who now serves as a vice chair of the Unicode Consortium’s emoji subcommittee. Hutchinson explained the idea. Could this work? she asked Lee. Would a flat shoe stand any chance of being added to the Unicode standard?

Yes, came Lee’s answer—and yes again. “She made a good point,” Lee told me afterward, of Hutchinson’s notional flat shoe. The world, according to emojis, has a relatively meager wardrobe: Compare all the types of food you can type into your phone—Swiss cheese, a lollipop, a tempura-fried shrimp, flan, paella, six more iterations of rice, so many drinks and fruits and desserts—to the full selection of clothing items currently available: three shirts, a pair of jeans, a teal dress, a kimono, and a bikini rendered in pink polka-dots. Lee, for her part, was glad to see a proposal for an emoji that would extend the vocabulary people have for talking about the things they put on their bodies every day. “I think clothes in general,” she says, “are an area of the emoji vocabulary that needs to be rethought and done in a more systematic way.”

With that encouragement in hand, Hutchinson got in touch with Aphee Messer, the Nebraska-based graphic artist who primarily works as a children’s book illustrator but who is steadily gaining a reputation as a go-to designer of emojis: Messer, she told me, has created designs for a piñata, a sauna, a salmon, a lighthouse, and many more. Perhaps most famously, she worked with Rayouf Alhumedhi, a Saudi teenager living in Germany, to design the emoji that was added as part of the Emoji 5.0 set earlier this year: one officially named the “Person With Headscarf,” but more popularly known as the hijab emoji.

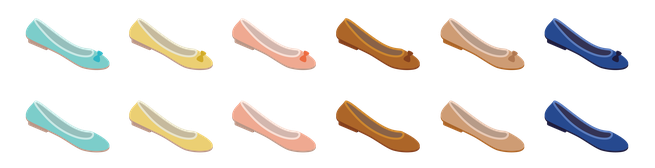

After Hutchinson sent Messer some inspiration images of flat footwear in the wild, worn by women around the world, the designer created a digital flat shoe, ballet in style and lined at the edges, with a few variations: one with a decorative bow over the toe box, and one without. (When it comes to emoji design, simplicity is key—during the creation process, “I’m constantly zooming in and zooming out,” Messer says, to make sure details will scan in smartphone-friendly sizes—as is cross-cultural legibility. Given emojis’ universality, she notes, it’s crucial to make sure that colors and other design elements will be user-friendly to people around the world.)

Messer, in the end, created a ballet flat that was angled, like the Man’s Shoe and the Running Shoe, at a jaunty 45 degrees. This makes it another departure for a woman’s shoe emoji: The keyboard’s other feminine-footwear options, from the boot to the sandal to the stiletto, sit flat. They suggest stillness rather than motion. Messer also rendered the design in a range of colors: teal, yellow, peach, brown, taupe, and royal blue. (For her part, Hutchinson says, she was open to anything except pink, red, and purple: pink for obvious reasons, purple because it is already so often associated with women in the emoji lexicon, and red because, even in a flat-shoe form, it suggests the vixen-y vibes of the stiletto.)

In July, Hutchinson submitted an application that explained how a flat shoe fits the Consortium’s criteria for new emoji: She offered data about the popularity of the flat shoe—#flats and #flatshoes had appeared as hashtags on Instagram 5.3 million times, she noted—and about the distinctiveness of the image she and Messer had created together. She made the case, essentially, that a world with a flat-shoe emoji in it would be incrementally better than the one without it. For the requisite submitter’s bio, Hutchinson wrote:

Florie Hutchinson is a Palo Alto–based mother of three young daughters who is an emoji enthusiast and would like to address implicit gender biases when she is not promoting artists and museums through media strategy work. In addition to offering an alternative to an erotic fire-engine red stiletto heel shoe, she hopes to raise women who are proud to wear flats and have an emoji that confirms that their height and leg lengths are perfect, as they are.

In August, the Consortium announced the 67 finalists for inclusion in the next round of Unicode emoji updates. The list included a cupcake, a kangaroo, a lab coat, a “leafy green,” and, as a 2017-appropriate answer to the iconically grinning version, a pile-of-poop emoji featuring a frown. The list also included Hutchinson and Messer’s ballet flat: The finalist version was rendered, per the color selection of the Consortium’s emoji subcommittee, in royal blue.

Next week, that committee will take its final vote about the makeup of Emoji 6.0; in November, the group will announce which of its finalist-emojis will become part of the Unicode standard—which pictographs, in other words, will be added to the visual vocabulary that is shaping human communication across geographies, ethnicities, genders, religions, and languages. From there, Apple, Google, Microsoft, Samsung, and other vendors and services will incorporate the new emojis into their own platforms, rolling them out over 2018. “In theory,” Hutchinson says, “you could see my blue flat shoe as early as March on your phone.” Which, she adds, is exciting—not just for her, but for the idea of collaborative meaning-making. “I mean, how often do we get to build a vocabulary from the ground up?”

Jennifer 8. Lee hopes that more people like Hutchinson—people who might not be coders, but who are fluent speakers of emoji, and who care about how it evolves as a paralanguage—will soon be contributing to that vocabulary. After her work getting the dumpling emoji standardized, Lee helped to form Emojination, an organization aimed at helping the people who want to create emojis to navigate the Unicode Consortium’s application process. Emojination connects people to graphic designers like Aphee Messer. It helps them refine the arguments they make to the Unicode Consortium, about why their emojis should exist. And members of Emojination are part of the Unicode Consortium—there among the representatives of the major tech companies, many of them American, to, as Lee puts it, “represent the voice of the people.”

Emojination worked with Rayouf Alhumedhi to get the hijab emoji included as a Unicode character. It worked with the Finnish government to get a sauna emoji approved. It assisted with a proposal for a mosquito emoji—a public health-oriented entry submitted by representatives of Johns Hopkins University and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. (The mosquito is being considered, along with Hutchinson’s flat shoe, for inclusion in this month’s Unicode Consortium vote.) In early 2018, in New York, Emojination will be hosting another iteration of 2016’s Emojicon, a general “celebration of all things emoji.”

The members of Emojination, along with their fellow emoji advocates around the world, will have much to grapple with as they do that celebrating. Are emojis, as they advance—as we, collectively, advance them—becoming too detailed, too cartoonishly photo-realistic? Are they too American? Are they too self-conscious? Are they too bureaucratic, too commercial, too corporate? Are they losing their early, easy whimsy? Are they trying to do too much, in a form that can never be enough?

Maybe. And maybe. And maybe again. Still, there’s something about an effort that is striving to be universal, that is trying to be more inclusive, that is opening itself up to contributions from anyone who takes the time to put together an application. There’s something about a global lexicon that is being built, methodically and intentionally, before our eyes. And there’s something about emojis themselves: those unions of communication and art, those shimmering expressions of human desire and delight and pain and wonder, those tiny pictures that take a language and expand its possibilities, one 🐨 and💃🏿 and 🐣 and 🌈 and 💯 and 👠 —and also, perhaps soon, one blue ballet flat—at a time.