Vida Goldstein, born in the Victorian city of Portland in 1869, was the first woman in the western world to nominate for a national parliament. If that was all she stood for, her name would simply be the answer to a pub quiz question. But Vida was one of Australia’s foremost women of courage and principle. All her life she fought for women’s equality – and her battles resonate to this day.

When Australian women were granted the right to vote by an act of parliament in 1902, the rest of the world recognised this new country as extraordinarily progressive. Women all over the world envied their Australian sisters – Vida was even invited to the US as a representative of “Australia, where women vote”. In her five months there she formed friendships with prominent suffragists, gave many speeches and even met the newly elected president, Theodore Roosevelt. (The leaders of the US women’s suffrage movement impressed her more than he did.)

On her return to Australia she stood for the Senate in Victoria in the 1903 election as a progressive independent, declaring that only women could properly safeguard their own interests and those of their children. Her overall message was also clear: “We women want the same freedom of thought and action as extended to men.”

Much of the popular press found the idea of a female parliamentary candidate hilarious; lawyers rushed to the constitution to see whether Vida was even eligible, and much of the press commentary was hostile. None of this fazed her, and three other women also nominated for election that year.

For two months she toured Victoria, attracting record crowds wherever she went. On the hustings, she was witty and nimble. “Woman is referred to as the clinging vine and man as the sturdy oak,” she said. “Well, I have seen the clinging vine bending over a washtub and the sturdy oak trying to hold up a lamp post in the street.” And she gave no quarter to hecklers. When a man interjected with, “Don’t you wish you were a man?” her reply was, “Don’t you wish you were?”

In her first election, Vida received about half the votes of the most popular Victorian Senate candidate. She made four more unsuccessful attempts to be an MP, both in the Senate and in the House of Representatives. She was unsuccessful each time, but she remained fearless in her pursuit of her principles.

Her last campaigns took place during the first world war; she vehemently opposed the then prime minister Billy Hughes’s two attempts to introduce conscription for overseas service. Defying not only the government but a large part of the population, she led public meetings – returned soldiers set fire to her platforms several times – and took steps to see that women and children did not starve while men were away fighting. When conscription was twice defeated, she felt vindicated.

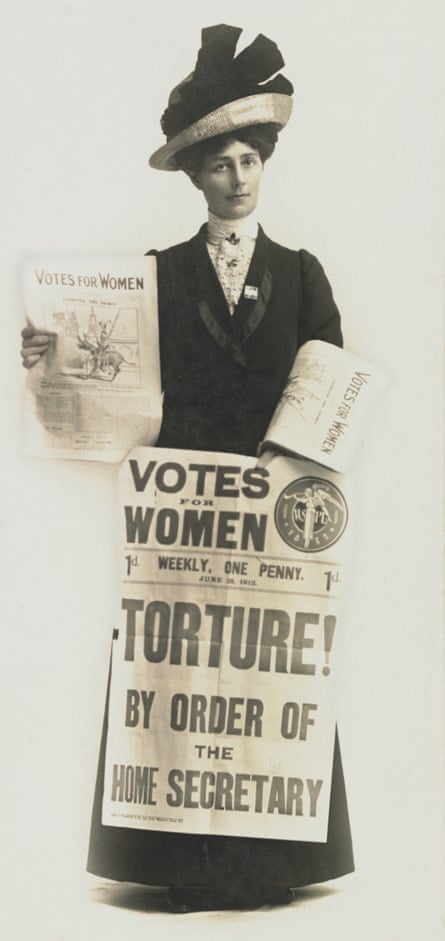

For some years, Vida was an international celebrity. Among her friends she counted the English suffragettes, including the Pankhursts (whose militant methods she basically supported) and the prominent Americans who supported the suffrage, as well as women from Germany, Turkey, France and elsewhere.

Writing Vida’s life story was a surprisingly emotional experience. It’s impossible to research and write about everything she did, all she faced and achieved, without cheering her on. But her story is also enraging.

Vida Goldstein was a woman of great ability, courage, intellectual force and determination: surely an asset to any parliament. Had she lived in the US or the UK, where she was lauded and admired, I believe she would certainly have been a member of the national legislature. Both countries had women in parliament or congress within five years of them gaining the vote; in Australia though, it took 40 years after women won the vote to see them take a seat in parliament.

This is no coincidence. In October 2019 Tanya Kovac, the national convenor of Emily’s List Australia – a political network supporting progressive Labor women seeking election to political office – said, “It’s as if [party organisation] is men’s business. It’s handed out along factional lines and not based on competency. Men have been the primary beneficiaries of that.”Women from all sides of politics would surely agree.

Vida would have been delighted to see Julia Gillard as the country’s first female prime minister. She would also have recognised the misogyny that crashed around Gillard’s head; Vida’s version of the “ditch the witch” placards Gillard endured was her own fear that her conservative opponents would release live rats or mice on to the platforms on which she spoke.

She would have been dismayed by the signs that, in political terms, women are still the unequal half of Australian society. Yet she knew that “the world moves slowly”, as she said in 1903. Let us hope she continues to be right when she added, “but it does move”.