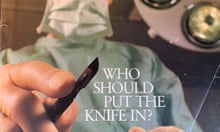

An old boys’ network, exclusion from events, scepticism from patients and incompatibility with family life are among the factors fuelling a dearth of women in surgery, research has revealed.

According to NHS figures for 2018, 1,138 women and 959 men were undertaking their first foundation year of medical training. However, only 14.5% of those at the top of their profession were women, with 1,389 female consultants to 8,164 male.

A small survey of women working in surgery has attempted to examine why so few pursue a career in the field.

Writing in the journal BMJ Open, the authors report how they posted a survey on both Twitter and a Facebook group for women of the Association of Surgeons of Great Britain and Ireland in October 2017.

Of the 81 participants, who spanned all levels of training, 88% said they felt surgery was a male-dominated field, with 53% citing trauma and orthopaedic surgery (which deals with the musculoskeletal system) as sexist – the highest proportion for any speciality. Overall, 59% of participants said they had experienced sexism.

When it came to barriers for women, 34% said they felt the surgery profession did not make motherhood or a family life very likely, while 16% said it felt like an “old boys’ club”. The same proportion raised childcare issues, while 10% flagged unsocial working hours as a barrier. More than a quarter said that other specialisms offered a better work-life balance.

“There is a culture that basically discourages females to pursue this career,” said Dr Maria Irene Bellini of Imperial College, London, first author of the study, saying that visibility of senior women in the profession is a key factor. “I strongly believe that you cannot be what you cannot see,” she said, adding that lack of support during pregnancy is another issue.

The authors say common themes emerged among written comments, including conflicts between personal life and career, the problematically rigid structure of surgical training – and blatant discrimination.

“I got told by another surgeon that he left vascular surgery for plastics because there were ‘too many women surgeons and they caused too much drama’,” wrote one participant, while another commented: “Patients don’t think women can be doctors, let alone surgeons.”

Bellini said such perceptions were damaging: “You feel like you have to fight not only against the institution for the way [it is] organised [to] favour men, but also some patients that don’t trust females because there is a general perception, dominated by unconscious bias, [that] this is a male-dominated field and a man’s profession.”

When the team asked how the field could be changed to retain women, 42% of participants said more flexible career paths and training were important, but almost a third noted that current flexible pathways are looked down on.

However, the study was small and reached only a subset of surgeons, and there could also have been bias in who answered the survey.

Bellini said the attrition of women in surgery showed something serious was amiss. “Why, if there is not discrimination, are the numbers what they are?” she said.

Scarlett McNally, a consultant orthopaedic surgeon at a hospital in Eastbourne who has been a surgeon for 25 years, said concerns raised by the research were very familiar. “This is exactly what women surgeons are saying and feeling,” she said, adding that structural changes, mentoring and tackling sexist behaviours are important.

“In all specialties, structures should be improved to make it easier for women and men – or the second parent– to take shared parental leave or less-than-full-time training. This would not only improve life for these doctors, but also show future cohorts that this is possible,” she said.

But McNally said the situation was improving, noting that the experiences captured by the survey could stretch back over decades, and there was now a legal maximum of working 48 hours a week – although surveys suggest some trainees work considerably longer hours.

“Now we only do life- or limb-threatening surgery at night. Hence we no longer need the heroic, sleep-deprived image of a surgeon; there is more team work and the learning opportunities can easily be focused into a shorter working week,” she said. “A variety of lifestyles is possible around this fantastic career.”