Female Athletes Need to See Puberty as a Power, Not a Weakness

I had the opportunity to safely and naturally grow a body durable enough to compete not only in college, but also beyond.

Updated at 1:06 p.m. ET on January 10, 2021.

When I was growing up, my natural ability was a big factor in my athletic prowess. With a wiry body and unusually long limbs, I managed to become one of the top young runners in California. I finished fourth in the state in my sophomore year of high school. At the same time, I was also developing an interest in other activities—student government, theater, competitive soccer, and a social life. But being a well-rounded teenager was not what my private high school’s athletic leadership wanted.

At the beginning of my junior year, they gave me an ultimatum: I would need to quit soccer so I could concentrate on track. My coach felt it was best to force high-school athletes to specialize. But this only applied to girls; the boys at my school were allowed to play multiple sports. That was the first moment that I realized the distance-running world is not structured to embrace female athletes.

I did not feel ready to specialize in anything, especially a sport I was good at but had not yet fallen in love with. I was a late bloomer, and I was gradually growing into the sport just as I was gradually growing into myself. So I left the track team.

The twist is that my forced retirement from high-school running became an advantage in my later growth as an NCAA and then professional athlete. I inadvertently stopped training just long enough for my body to go through puberty without the strain of overtraining. I grew C-cup boobs; I gained some weight. I rode the puberty wave and then, when the time was right, I gradually increased my training. As a result I was far more physically resilient, powerful, and capable than the female athletes who feel pressured to maintain a Peter Pan prepubescent body. Some coaches assume that if a girl lets her body mature naturally, she will never again be as capable as she was before puberty. But female distance runners usually peak in their late 20s and early 30s. Female athletic programs need to see puberty as a power, not a weakness. Our bodies take time to develop—a word female athletes need to embrace.

Many athletic programs, even at the collegiate level, fail to properly guide female athletes through young adulthood. Programs confuse health with fitness. Fitness is only an indicator of athletic ability at the present moment. Health is a more holistic measure of the body’s ability to endure strain. Fitness does not take into account that you need to continue training tomorrow and next week. It is better to be 100 percent healthy and 80 percent fit than 100 percent fit and 80 percent healthy.

Many female athletes are pressured to prioritize fitness at the expense of their health. The physical changes that occur between adolescence and adulthood—mainly weight gain as your frame expands and your body fills out—can seem burdensome at first, an impediment to fitness. I once consoled a college teammate after the coach called her into his office and made her hold a five-pound weight in each hand and pump her arms as if she were running, and then had her put the weights down and pump her arms again—a demonstration of how much easier it is to run after losing 10 pounds. To please their coaches and keep up with their male teammates, whose developmental trajectory is completely different, many female athletes overtrain and don’t eat enough during this critical growth phase. (I know female athletes whose periods were delayed until their 20s.)

The result of the systemic prioritization of fitness over health for young female athletes is that many girls will become frail and injury-prone by the time they’re in college. A runner I knew in high school is a classic example of overtraining and underfueling. While other girls were filling out and running slower times, she was thin, and muscular, and as fast as ever—until she broke. By the time she was a senior in high school, she was hospitalized for an eating disorder. She had injuries for almost her entire collegiate career.

Even though I took a two-year break from running at the end of high school, I was asked to join the cross-country team when I started college. Dartmouth’s recruiters had reached out to me based on my performance my sophomore year, and the coach was interested in my potential.

But when I reported to my first practice, I realized that I would no longer breeze to the top of the ranks as I had when I was younger. I couldn’t rely on my talent alone. After two years away from competitive running, my body had changed. It was humiliating to have to walk after only a few miles on easy training runs. I finished dead last in my first cross-country race. I was not only the last on my team; I also had one of the slowest times in the whole league. The first few semesters in college were a long trudge toward getting my fitness back. In the meantime, I found ways to stay engaged and contribute to my team even though I wasn’t competing. When the traveling squad went to New York City for the Ivy League Cross Country Championships, I found my own transportation to the race and went in costume to cheer them on.* I kept showing up, and I’m proud of how I handled myself during those few years. Yes, years. It wasn’t until the winter of my junior year that I contributed my first team point.

During this time, I also learned how to fuel my body properly. Food can be a sensitive subject for female distance runners, since we are often pressured to stay thin even as our bodies mature. At Dartmouth, some girls on my team limited their portions by only eating from the palm-sized side-dish bowls in our cafeteria, never actual plates. When I became captain, I instituted a rule that everyone had to eat proper portions off a real plate. During graduate school at the University of Oregon, I had a teammate who ate all her meals with chopsticks, one grain of brown rice at a time. Every school has cases like this (my friend at Brown reported that her coach had a “no booze, no boys, no bagels” policy), and I don’t know exactly what the right answer is for athletes who struggle with weight issues. Each person has an optimal “race weight range”—but for female runners especially, coaches and athletes should consider the athlete’s longevity and durability, not just the numbers on a scale.

By senior year, my six-mile runs became ten-mile runs, and six hours of sleep became nine. I had finally learned what worked for my body, and I competed in an NCAA Track and Field Championship for the first time. By then, the preternaturally talented prepubescent Alexi who placed high in state championship meets was long gone. The new Alexi was made from work, discipline, patience, pain, and lots of sleep. Stepping up to the start line for the first leg of the distance medley relay at the 2012 NCAA Indoor Championships felt like something I had fought for and earned. I even got matching tattoos with my relay teammates because we were so proud. We had set a lofty goal, worked hard, and made it happen.

I am grateful that I had the opportunity to safely and naturally grow a body durable enough to compete not only in college, but also beyond. I’m certain that if I hadn’t gone through puberty naturally and menstruated normally, my body would have broken down after just a few workouts in the professional world.

Too many young women quit the sport because the system makes them feel as if they weren’t built for distance running. It doesn’t have to be this way. I had two incredible female coaches in my career, Maribel Souther at Dartmouth and Maurica Powell at the University of Oregon, both of whom showed by example what a thriving female athlete could be. As more women take leadership roles in the athletic world, I hope more people know that female bodies operate on different performance timelines than those of their male teammates and require a different type of support. Starting as early as middle and high school, we can educate coaches and athletes on the proper approach that young women can take to embrace their bodies and stay healthy and ultimately grow into more capable adults.

Female runners, in particular, need to be set up for long-term durability. No matter how powerful the engine and how potent the fuel, the whole thing is useless if it burns out too soon.

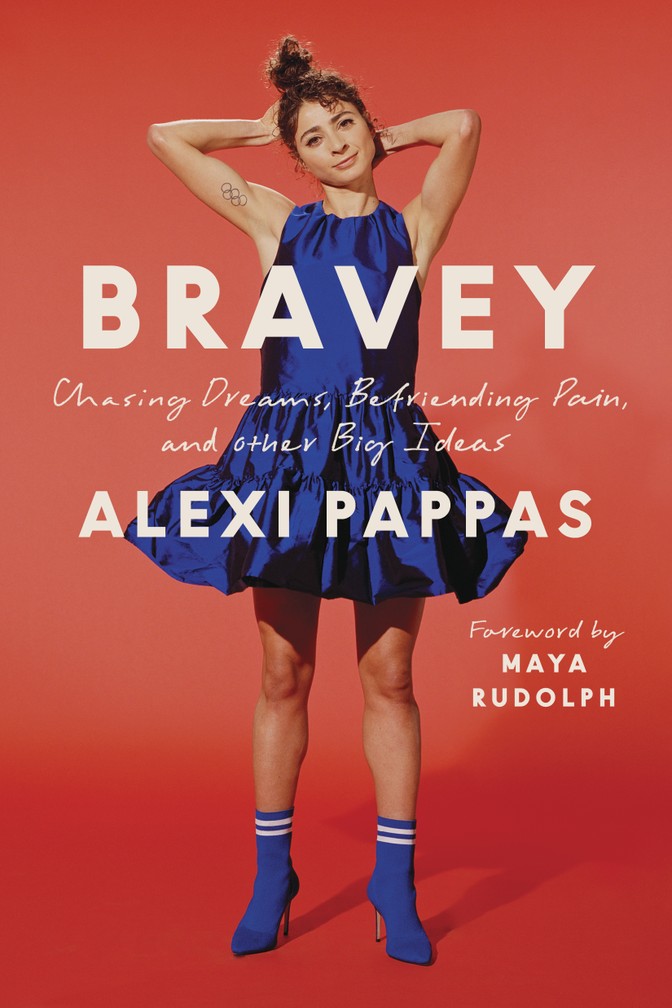

This article has been adapted from Bravey: Chasing Dreams, Befriending Pain, and Other Big Ideas by Alexi Pappas

*A previous version of this article misstated that Pappas attended a cross country race as a team mascot. In fact, she was dressed in costume.