The birth control pill was the first line of defense from unwelcome pregnancies—feminists like myself believed in the late '60s and early '70s—and abortion was the second line of defense.

During that time I had been living in New York's Greenwich Village, then in suburbia, working my way up the academic ladder to senior positions as a professor and dean at a City University of New York college, and also as an adjunct professor at New York University's graduate program.

Myself, and other pioneer feminists were working hard for the liberation of women in every sphere. Legalization of the birth control pill in 1972, regardless of marital status, was perceived as one such vehicle for liberation. It also helped to jump start the sexual revolution.

Prior to this, men generally had the responsibility for providing and wearing condoms—the most common form of birth control at the time. The onus was on him to prevent unwanted pregnancies, although the ultimate responsibility was born by the females if something went wrong or he was negligent. It would be she who would have to bear the child or seek dangerous interventions to circumvent its birth.

The benefits of the pill to both genders were obvious: a convenient solution that equalized and liberated both sexes. It reinforced our belief in the right of a woman to control her own fertility.

But there was a dawning recognition in the late '60s and early '70s around the fact that while men benefited from it, perhaps more than females did, they incurred none of the risks. And as it turned out, there certainly were risks to the health of women. And this troublesome issue created a subset of the women's movement, which became the women's health movement.

It took me a little while to take more seriously some of the medical and ethical concerns raised by many of my peers who were invested in this topic.

Barbara Seaman, who wrote The Doctor's Case Against The Pill in 1969, led the fight against the pill. She was a personal friend of mine, as were many of the pioneer women who founded second wave feminism.

She outlined potential dangers such as heart attacks, strokes, depression, breast cancer, blood clots and asked questions: Why isn't there a pill for men? Why should birth control be a female responsibility? Why are women being used as guinea pigs?

The fundamental question about whether the pill was safe forced us to examine and try to balance the freedoms we were winning because of it versus the liabilities, or potential liabilities that argued against its use.

And that was a very, very important issue, not just for the women in modern feminism, but also for mainstream American women in the early '70s.

In 1970, a Senate hearing examined health concerns about the birth control pill although women were not allowed to testify or speak. That was par for the course and exactly the way we were always treated.

But women from the D.C. Women's Liberation movement—"the Boston Tea Party of the women's health movement"—were in the audience screaming out questions and objections even though they didn't have any formal place.

They argued that this was just another example of patriarchal control over women's lives. And why do men (and this was a larger question) control the medical profession, and the pharmaceutical industry?

And that's where the birth control pill highlighted another issue that we pioneer feminists were all about, the inequity in professional opportunities for women at the time.

Because women were largely denied entrance into the law, medical and professional schools, and discouraged from the pursuit of academic and other advanced careers, they were not CEOs of corporations, judges or heads of hospitals.

We understood that there was a direct connection to the denial of educational and career opportunities for women and the male dominated society that ran the issue of the pill.

Women were not in charge of the pharmaceutical corporations; we were not the doctors and the researchers. We were not only absent, but systematically excluded.

The pill became emblematic of these fundamental gender disadvantages and disparities. Looking at it from a feminist lens, it was clear that that patriarchy controlled the dissemination, production and quality of the pill, and also hid its harmful side effects at the time.

We were left with the unhappy insight that men still had an outsized role in controlling the bodies and biological destinies of females. This was a major challenge and another act of oppression.

I met the feminist, author and artist Kate Millet, with whom I worked to improve educational and career opportunities for women, in 1958. Since we traveled in the same bohemian and intellectual circles it was inevitable that we would eventually meet.

Like me, she was in her early twenties, just back from England where she had recently graduated from Oxford with First Honors—an unheard-of achievement for a woman at that time.

I had a newly minted degree in Philosophy and we immediately became close friends and intellectual sparring partners, a relationship which lasted almost 60 years until ended by her death. She introduced me to feminism, among many other things, brought me into the National Organization For Women (NOW) and together, we co-founded and led its first Education Committee.

A core issue for us was to change and upgrade educational aspirations and opportunities for girls. It has been humbling and gratifying to know that our work has impacted many successive generations of girls and women and that females now constitute a majority of attendees at universities and professional schools in the U.S. Happily, we now do have female judges, CEOs, doctors and college presidents.

Though the pill didn't impact me personally that much because I had my last child in 1974, I had used it earlier and understood its advantages.

When the pill first came on the market the initial reaction by feminists was a welcoming one—an outburst of relief, pleasure and joy that there was something that facilitated sexual freedom.

It aligned perfectly with our agenda, which was to give women the same sexual rights as men, and to remove morality and shaming issues. We were keenly interested in liberating our sisters from sexual stigmas like masturbation, homosexuality and prostitution.

But while the pill was helping with family stability, planning and the spacing of children—you could control numberless children from spouting every nine months!—on the other hand, it was potentially destructive to the unity of the family.

Sexual freedom also spawned free love, wife-swapping, promiscuity, open marriage and created all sorts of unexpected consequences and practices.

What was intended to give relief and stability to the family was also potentially a dagger at the heart of the family. It was an interesting and knotty contradiction.

It has been 60 years now since the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) first approved the birth control pill on May 9, 1960. In the end, with the mitigation of health concerns in the years since the early '70s, the birth control pill has emerged as an essential pillar of women's ability to have good quality of life, without being encumbered by unwanted pregnancies.

My hope is that younger generations, like my granddaughter and grandsons, are able to have optimally rich lives, actualize their talents and aspirations to the fullest level possible, and that they live freely, openly, happily and healthily.

We had a very hard time when we began this journey towards women's equality; it was a very harsh and a very unjust world for women in every sphere.

We did it for generations of girls and women yet unborn, so that they could fulfill their aspirations and professional desires, not live in a closed society and restrictive world hostile to their dreams.

Things have changed, and I attribute that to the work of my colleagues in early feminism. They have substantively changed the world, and the birth control pill is just another tool in the arsenal for women's freedom and advancement.

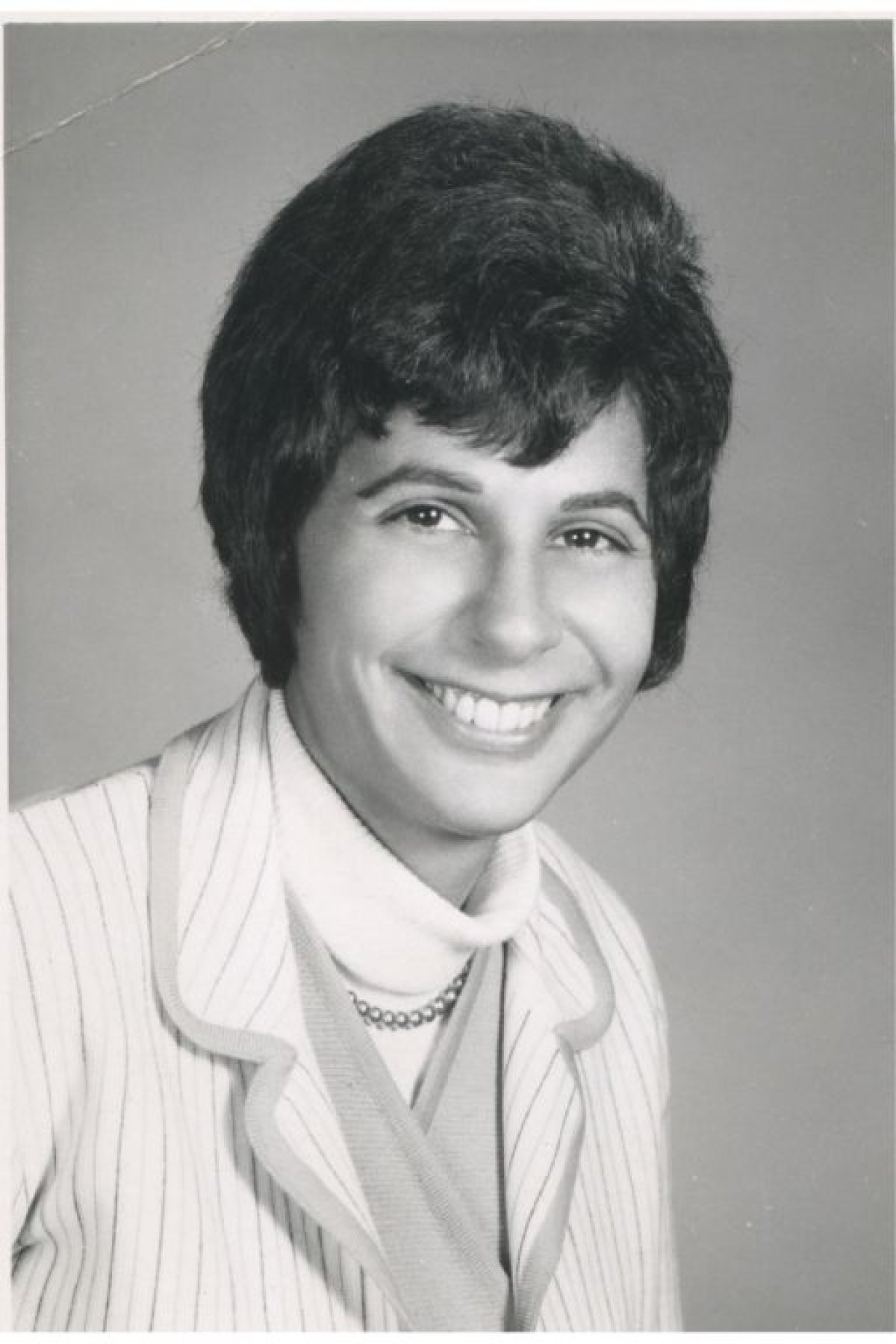

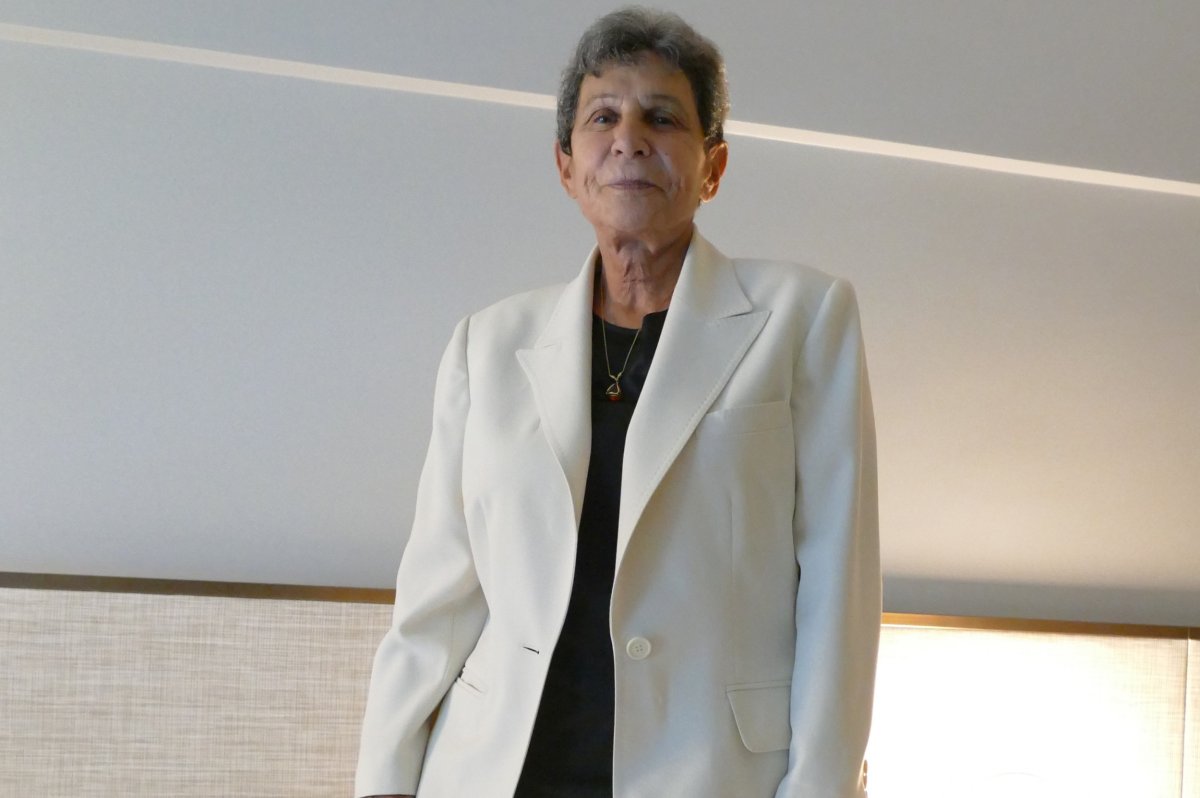

Dr. Eleanor Pam holds three advanced degrees and is Professor Emerita at the City University of New York where she was a member of the faculty and held senior administrative positions for 34 years. She has received many academic honors, citations and awards for her pioneering contributions and leadership in the area of women's rights.

The views expressed in this article are the writer's own.

As told to Jenny Haward

Correction 05/09 10.14 a.m.: this story has been updated to accurately include the name of the National Organization For Women (NOW).

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.