Content warning: This story contains graphic details of grooming, sexual abuse, and violence.

It went like this: A teacher would insinuate himself into a circle of young women. Train his attention on one in particular. Find reasons to touch her, spend time with her, get her alone. Cross boundaries, with devastating consequences. And because the women were manipulated, threatened, isolated, and ashamed, they didn’t talk about what happened. They didn’t know there were others. Until they did. And they filed a lawsuit.

The man is Mitchell Taylor Button, a former dance instructor known to his students as Taylor. He’s the husband of Dusty Button, who was a prima ballerina of the esteemed Boston Ballet and a wildly popular dance influencer on Instagram until her career came crashing down in the wake of allegations that she and Taylor sexually abused the young women in their sphere of influence.

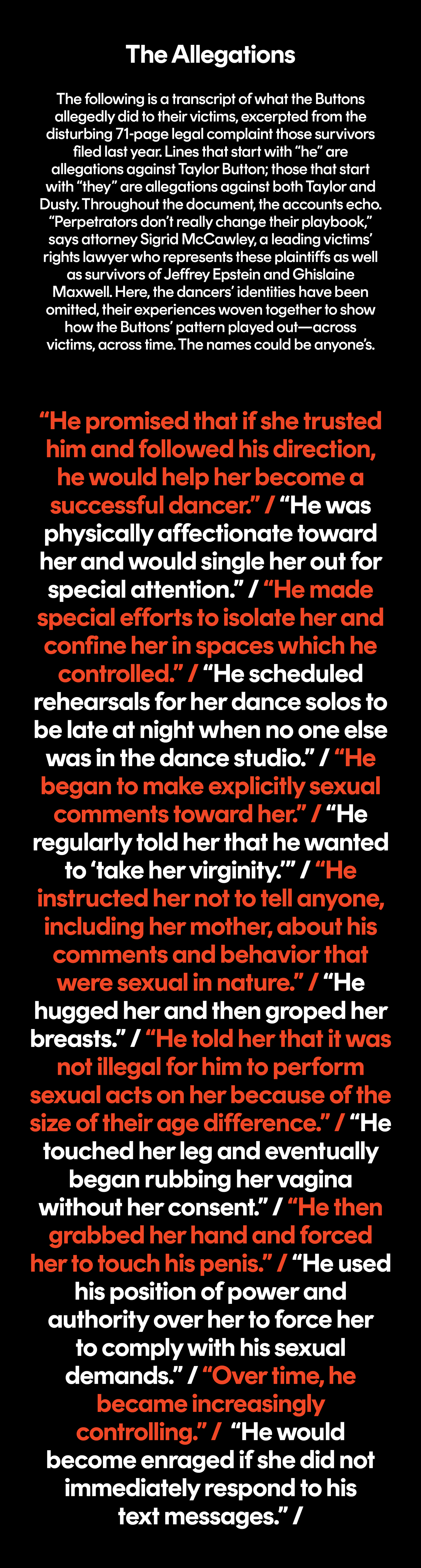

The legal case, first filed in July 2021, is ongoing (the Buttons have filed a motion to dismiss in which they deny any wrongdoing; when reached by Cosmopolitan, their attorney declined to provide additional comment). The accusations at its center are harrowing, detailing a predatory pattern of grooming, coercion, molestation, sexual assault, and, in some cases, battery, perpetrated over the course of at least a decade.

The arc of these stories—among the seven plaintiffs in this case and in broader narratives that have played out in recent years on the global stage—is painfully familiar. Hollywood. Media. Gymnastics. Now, another subculture of silence is crumbling.

It’s typically the shocking details of these abuses that get remembered and then tangled, for the rest of her life, around the person who survived them. So we’ve decided to tell this story differently, separating the specifics of the alleged crimes (at the bottom of this page) from the women they were committed against. Rosie. Dani. Gina. Sage. This is who they are—which isn’t the same thing as what happened to them—and what they hope will happen next.

Rosie was always the one who remembered the choreography during recitals. Other kids, off in their own worlds, might toddle into the wings, sit down, stick a thumb in their mouth. Not Rosie. She followed the steps, felt the beat. From a young age, that talent—to arrange herself into the right shapes, to commit a combo to memory—was a double-edged sword.

“There is an innate ability to take an idea, put it in my brain, and transfer it through my body,” she explains. “But at the same time, I think dancers can be at a disadvantage because we’re taught to turn off our instincts, not to listen to that feeling of ‘I’m tired’ or ‘I need a break’ or ‘that hurts.’ It’s something I’m trying to undo in myself.”

When Rosie met Taylor, she was new to Centerstage Dance Academy in Tampa, Florida. He was a popular teacher. In his early 20s, he seemed to have an easy rapport with the other dancers. Rosie wanted them to like her, so she decided to go with the flow. Even if it meant downplaying his unsettling attention. Like how he would insist on taking her out to lunch. And how he slid sexual innuendos into their conversations. Later, after he cornered her alone, he manipulated her into believing that nothing bad was happening to her. He claimed it wasn’t illegal because he wasn’t that much older.

“It’s the easier thing to trust, when you’re a teenager and learning how to love people,” she says. He was her mentor; he told her it was okay. She wanted to believe him. Except the things he said and did left her confused, disoriented. Like she was underwater in complete darkness, with no clue about which way was safe to swim.

Senior year of high school, she switched to another studio to get away from him. She felt ashamed and also fearful of what could happen if she talked about it. The trauma was always there, circulating within her body. She compartmentalized. Told herself it would be okay. But it wasn’t. She only started getting better when she stopped keeping it all in.

Today, Rosie is still dancing. Now based in New York City, she’s the artistic director of a small performance collective. She auditions, choreographs, and teaches yoga to kids at an elementary school. She works out phrases of movement in her empty living room, physical expressions of what’s going on in her mind—a dialectic in clips posted on Instagram.

“We all have a body. We all have an ability to connect with that body,” she says. “Some of us are further away from knowing what that means.” Listening to ourselves—paying attention to our own intuition—is essential to building that connection, Rosie explains, to finding our footing, expressing the thing that we’re trying to say. To recognizing something for what it really is.

Another rehearsal room, in 2021. A young dancer raises her leg in a shaky développé. Dani gently adjusts the girl’s balance and turnout; the extension unfolds, longer, higher. “As a teacher, you’re constantly correcting,” Dani says. But you have to be careful with criticism, even the constructive kind. “A lot of kids will receive that as: ‘I’m bad.’ And they need our help.” Her calling, she decided years ago, is to help them. To leave them better than when they came through the door.

Dani didn’t always plan to teach. Around the time she turned 15, she started to think about dance as a viable career path. Imagined moving to Los Angeles, trying out for movies, commercials, music videos. But big cattle-call auditions make her feel empty, so she turned her focus to choreographing and instructing classes instead. She knows, from personal experience, that the right teacher can change everything.

So can the wrong one. As a teenager, Dani was taking classes at Centerstage, around the same time as Rosie and Gina. That’s where her story first intersects with Taylor too.

First, he was her teacher who told her she was like his “little sister.” Later, he said their age difference didn’t matter. “I had a perfect childhood, wonderful parents—I never knew people like this existed,” she says. And because she didn’t know, “I didn’t recognize the warning signs.”

Their “relationship” affected everything: her mental health, her sense of safety. Even where she went to college—he convinced her to stay local. And because he didn’t want her partnering with other men in classes there, she paused on studying dance. He yelled, berated her in public. If someone attempted to intervene, he scared them off by becoming belligerent. She started believing no one could help her. In the worst moments, she was afraid for her life.

Sometimes she feels overwhelmed and angry about the sheer volume of stories like hers. “Where are the good people?” she wants to know. “As much as we see all these horrible stories and all these people’s trauma, there’s still not enough education about what to look out for. Like, ‘These are the steps, and if you find yourself in this situation, you need to get out. Now.’”

“Every time I talk about this, it’s scary—I have to gather up my strength and bravery and keep reminding myself of the bigger purpose,” Dani says. “I want people to be educated enough not to have the same experience.”

With her own students, she talks about red flags, about boundaries. They call her The Therapist. “If the kids have something—anything—going on in their lives, they know I’ll help them.” Just teaching a dance combination doesn’t cut it. She wants to do more.

Gina’s mom put her into classes when she turned 3, a whirling gale of shiny brown curls. Jazz, tap, Afro, ballet, hip-hop—it was like movement had been waiting for her. By the time she was 12, she had already decided: This was what she wanted to do forever.

She grew up in Florida, made her way to Los Angeles. In 2019, she competed on NBC’s World of Dance before trading L.A. for New York. All the while performing, choreographing—and teaching, the pursuit that matters the most now, after what she went through.

“The biggest lesson I want to give my students is the confidence to know: Even though they’re young, they are smart. Their instincts are correct. If someone makes them feel uncomfortable, if people overstep, they should follow that gut feeling,” Gina says. She felt it herself, in her early teens. Back then, she was taking classes in Tampa, at Centerstage. She was in awe of him. Taylor. He’d worked with big names; he could help her achieve her goals in the professional dance world, he promised. When he singled her out for a solo opportunity, she was elated. Looking back: “It’s the first memory of when the grooming began.”

On her 14th birthday, he gave her a teddy bear sprayed with his cologne, so she could feel like she was “sleeping” with him, she remembers. He devised reasons for them to be alone together. It went on for a year and a half. “The thing about being a young dancer is we’re trained to seek approval. You don’t come out of the womb knowing you shouldn’t be touched or talked to like that by someone twice your age,” Gina says. “I know now. I didn’t then.”

In late 2010, when rumors began circulating about his inappropriate behavior, Taylor left the studio. He moved to London, married Dusty, took her last name. Gina felt “destroyed,” she remembers. He made her believe that telling anyone about “them” would ruin her career, weaponizing her own hopes for the future.

“No one really helped me.” That’s what it feels like, when she thinks back. In 2018, she filed a police report and a detective worked the case, a drawn-out process that ended with the devastating news that there wasn’t enough evidence to go to court. When Gina heard that, she lost it. A mentor gave her some advice: Put the abuse in a box. Keep moving. Move on.

She tried. Years passed. She imagined him out there, in contact with other young dancers, making the rounds at conventions. It scared her. Slowly, she started telling more people what had happened. Then another dancer connected her with Sage, who put Gina in touch with the attorneys now leading the lawsuit. She felt stronger, found purpose in the thing she’d been through: helping make sure it didn’t happen again.

“My trauma, my PTSD: It’s always there,” Gina says. But the box is open. She’s not afraid of what’s in it anymore.

Consider the physics of a pirouette, the centrifugal force of a body in motion. The torque. The friction of the floor, which makes turning possible but also stops it, eventually. When Sage was small, her nana would drive her to the dance studio and watch her practice for hours. That’s where she fell in love with that feeling: the self-contained revolution of a spin.

She kept turning. At 12, she was accepted into the School of American Ballet summer program in New York City, attending three summers in a row, followed by a rigorous Russian-style studio in Southern California, close to home. Soon, she appeared in a docuseries, Dance School Diaries, as she geared up to compete in the Youth America Grand Prix competition, its own kind of Olympics. A contract with Ford Models—a detour—and then back to training that landed her at Boston Ballet.

That’s where Dusty approached her, in 2017, around the time Sage was offered a contract with the company. Dusty was already at the height of her career, the pinnacle of what every dancer aspired to, and Sage was starstruck. Now, she thinks of that first “hello” as the moment her world darkened.

Their friendship began in the studio. Then Dusty invited Sage to come to her apartment. The walls were painted black. In one room, a collection of guns was displayed. That’s when Sage met Taylor. She remembers he asked her a stream of questions: about her life, her relationships, her family. Later, when he offered to manage her social media, it made sense to say yes—Dusty had a huge following, hundreds of thousands on Instagram. Taylor got the passwords to Sage’s phone, email, and accounts. That’s when he started monitoring her communication. Infiltrating everything.

Soon, she was spending all her time with the Buttons. Sage recalls being on the train once—a rare moment alone—and realizing she was trapped in a nightmare. “This was calculated. These people are predators. This is a pattern,” Sage says. But she didn’t know how to make it stop.

Then came spring, when Dusty was fired from the ballet, and Sage’s parents arrived for a surprise visit that turned into an intervention. With the help of a rehearsal director at the company, they whisked her away. It took months of work to begin to unravel the mess in her mind. Later that year, Sage returned to work in Boston.

“I used to think ballet was a safe place,” she reflects. “Now it’s interesting to me how the most evil people hide in plain sight, where no one would suspect.”

If you or someone you know has experienced sexual violence and wants support or information about how to find help, call the National Sexual Assault Hotline at 800-656-HOPE or visit Hotline.RAINN.org.