Ken Burns and Lynn Novick started working on their new docuseries about Ernest Hemingway almost seven years ago, when conversations about toxic masculinity and cancel culture were still at least a presidency away. But you’d be forgiven for thinking the series was a pandemic project, because Hemingway, and the conversations that take place within it, feel utterly of the moment. From gender fluidity and mental illness to sexual misconduct and racism, today’s most charged topics are discussed at length in the series because they were part and parcel of the iconic, mercurial writer, whose own ex-wife Hadley Richardson once described as having so many sides to him that he defied geometry. Throughout the three-part, six-hour series, Hemingway is portrayed as both violent and tender, self-aware and self-aggrandizing, with an equal, outsize capacity for both joy and depthless depression. It’s no wonder then why the writer Michael Katakis says at the start of the series that Hemingway the man is so much more interesting than the whiskey-doused, hypermasculine myth that obscures him. In separate interviews, Burns and Novick walked us through how making the film transformed the way they understand Hemingway—the man, the myth, and his literary legacy. Below, we’ve spliced together the two conversations, which have been edited and condensed for clarity.

Abigail Covington: What originally drew you to Hemingway as a potential subject?

Lynn Novick: Ken and I have slightly different versions of this because we both came to it in different times and different ways. For me, I am an inveterate reader of fiction. I first discovered Hemingway when I was in high school English class where we read The Sun Also Rises. Reading it opened up for me what a book could be, what characters could be, how to tell a story. There was kind of a romance and a mystery in the book. It gave me access to a world that I couldn’t have conjured on my own. After that, I read Hemingway on my own and discovered the short stories and the novel A Farewell to Arms, which is my absolute favorite. So I became interested in him in a way, but I wasn’t thinking about making a documentary about him. I just loved to read his work. I was also fascinated and somewhat repelled by his public persona.

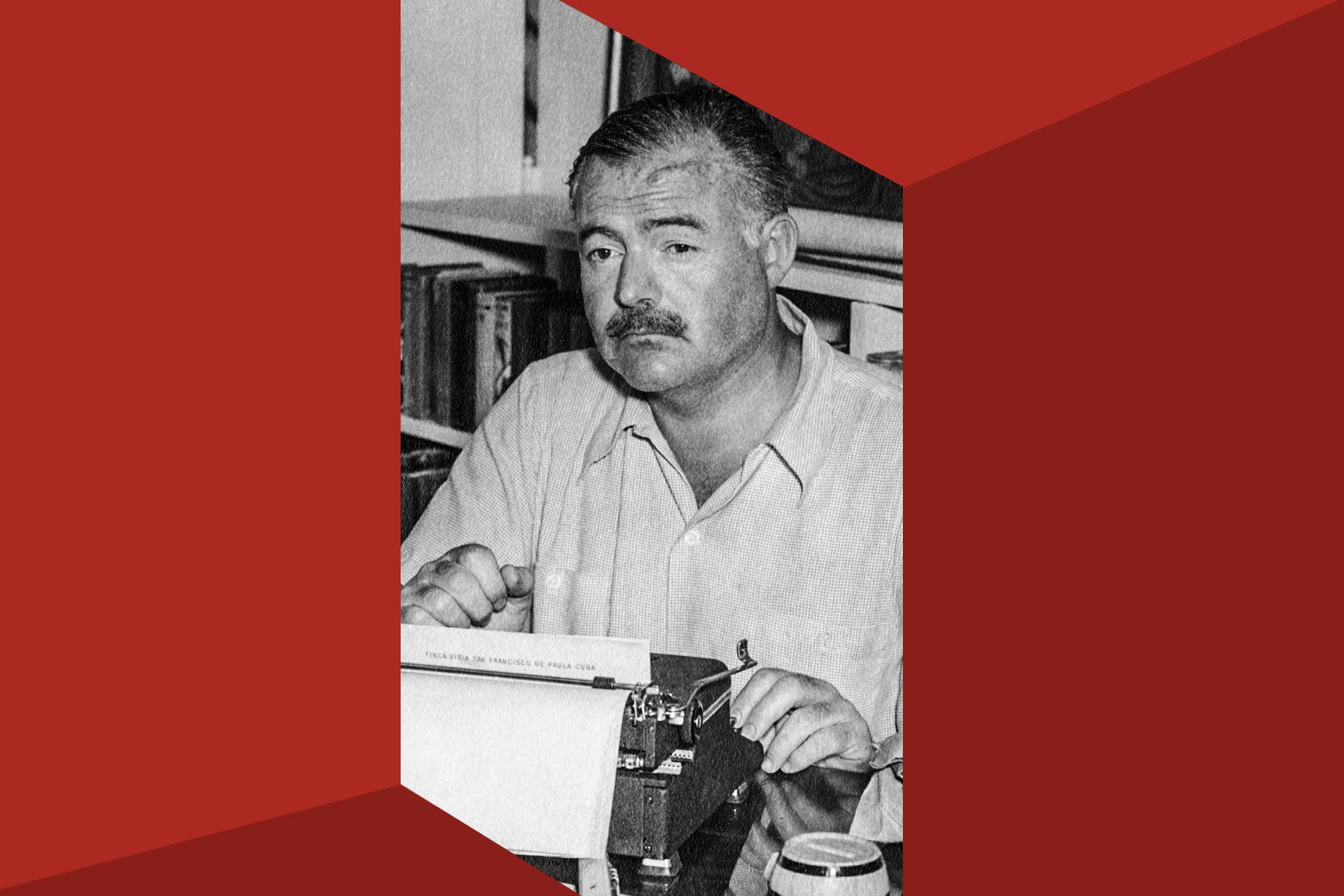

Fast-forward to the mid-1990s when I had been working with Ken on the Civil War series and Baseball series, and I happened to go to Cuba on vacation. It wasn’t like I consciously decided, “I’m going to Cuba to go to Hemingway’s home,” but when I decided to go there it was high on my list of things I had to do, for reasons I can’t explain. Walking into his house and then going into his work room and seeing his typewriter, it made him real to me. I could almost feel his presence in the room. Hemingway is very, very important in the history of literature—certainly American literature. He lived so large, he led this oversized life, and I knew then he would be a great subject for an iconic American story.

Ken Burns: Well, we’d been thinking about him for literally decades. It’s been 40 years. I found a scrap of paper that I’d written down from the early ’80s. It had potential topics on it. After the Civil War, it said, “Do baseball and Hemingway.” There were four or five other topics, half of which we’ve done and the other half, I don’t even know where they went. Lynn got really into it after she went to Cuba and had been really blown away by feeling his presence there. We just kept kicking the can. Sometimes somebody says something to me and I say yes, right away, and sometimes it has to incubate for a few years.

When we finally started working on it six and a half years ago, we quickly learned that we had no idea how difficult—in a good way—it was going to be to pierce the veil of mythology about Hemingway, that he helped to construct and the world helped to construct, but that kept him isolated. I think it’s because he’s such a good writer, and he’s such a mystery that the myth is able to obscure something that’s going on that’s clearly more interesting than all of that façade. He is vulnerable, anxious, and insecure. He’s an enormous noticer. He sees the world, both the natural world and the human world, so clearly. He sees the worst things we do, like war, and brings it back with a spare prose that betrays all of the meaning that is lurking between the words and the lines. Also, he had an androgyny to him that allowed him to put himself in the position of a woman. So we began to understand that for all of his bravado, there is also a curiosity, sympathy, and even a gender and sexual fluidity to him. His toxic masculinity never evaporates, but it’s not all that’s there.

A lot happened in America during the six years you were making this series. The election of Trump, #MeToo, cancel culture, wokeness. How, if at all, did the surrounding cultural climate influence the direction of the film?

Novick: It influenced us in obvious ways and not so obvious ways, and in conscious and unconscious ways. Already in 2014, a big question for me and our producer Sarah Botstein was, “As women, what is our relationship to Hemingway the human being, the public persona and to his work? What would he have to say and what will our film have to say to women readers and women viewers?” We thought about those questions a lot when considering who to interview, what to ask them, and how to frame the story, because it is an investigation into masculinity that we understand is very problematic.

One of the really salient moments for Sarah and me was going to a Hemingway conference. We were struck by the fact that in this auditorium of 1,000 people, half of the people were white men of a certain age who seemed to be channeling their idea of what Hemingway represented: a lot of beards and hunting vests. Then the other half of the room was full of younger women, many queer and gender nonconforming women, who were exploring questions of Hemingway and identity, gender, masculinity, and looking at his work through a completely different lens and finding a lot there to sink their teeth into. It was really fascinating to see where Hemingway scholarship was going, where it had been, and how he is being reimagined for a different generation. That was in 2016. So I guess what I’m saying is we were interested in exploring, particularly the question of women and Hemingway and gender and Hemingway, before #MeToo became a thing, for sure.

There certainly is a lot in the film about his exploration of gender and sexuality, starting in his infancy and going all the way up through role-play in his marriage.

Novick: I vividly remember going to a concurrent session at the conference about teaching Hemingway and gender. During the presentation, a scholar named Hilary Justice described an experience she had teaching Hemingway. There was a young woman in her class who came in one day and said, “I hate Hemingway! He’s a misogynist, and I don’t want to read him.” And Hilary said to her, “OK, take this pink highlighter and go home and read these three short stories and highlight the passages where you see Hemingway’s misogyny.” Well, the student couldn’t find what she was looking for in the fiction. So that became a meditation on finding a way between Hemingway’s public persona, his personal life, and his work. We tried to explore all of those things and to show where he may have behaved in certain ways that were really unacceptable to us today, but in his work he was exploring the toxic consequences of some of that behavior.

I appreciate what you’re saying in terms of seeing how he was trying to wrestle with his chauvinism in his fiction. Edna O’Brien reflects on all of that quite charismatically in the film. But I don’t think Hemingway’s ability to channel self-awareness and guilt through his fiction excuses, or complicates, or even makes more interesting the very real misogynistic behavior that he exhibited in his own life.

Novick: I completely agree. We as human beings can condemn certain behaviors and aspects of his life while also seeing things in his work that are interesting and complicated and worth reading. One doesn’t cancel out the other, or excuse the other, or explain the other even. They are just both true.

What was your strategy for documenting Hemingway’s mental illness? Did you know from the outset how much it should factor into the overall story of his life?

Novick: No. None of us really knew that much about it going into this. I think we were reluctant to be too hard and fast with any kind of psychiatric diagnosis on someone who has been dead for 60 years. On the other hand, we also wanted to use words that are not stigmatizing. We wanted to describe what the symptoms were that people around him could see and that he himself described in his own mother’s serious depression. We were very intrigued by a book that came out called Hemingway’s Brain in which the author made an interesting argument that everything that happened to Hemingway could be traced back to the many concussions and traumatic brain injuries he suffered throughout his life. There is also clear evidence of a mood disorder from a young age, and the family history of mental illness is there. There was a toxic combination of multiple things.

I also want to say, my partner is a psychiatrist and also a documentary filmmaker. When I started working on the project in earnest, I talked to him a lot about what I was trying to understand in terms of what was going on with Hemingway. He and some of his colleagues helped me personally get a handle on what we could say and how to handle this responsibly. Most importantly, we didn’t want to stigmatize mental illness. That was front of mind for me.

Burns: This is the problem with documentary films. People have a short research period, followed by a short writing period, which produces a script that informs the shooting and editing. Boom, done. We worked for six and a half years. We dropped our baggage at the beginning. I don’t know where that baggage is. Instead of telling you what you should know about Hemingway, we shared with you our process of discovery. That’s the key to every film I’ve ever made. Every single film has been about sharing a process of discovery.

So, how do you work that in? Don’t we need to go and talk to a forensic psychiatrist who can help us? Yes, let’s talk to this person who has written about Hemingway’s concussions. Do we need to cut it back because that person never examined Hemingway so a lot of this is speculation, and we know that’s not a good practice? Yes. So how do you carve it back in an honorable way that doesn’t take away from his own message but that also takes into account the things other people say?

We weren’t going to put all of our eggs in the concussion basket because we also knew about the family history of mental illness and addiction. It’s a question of being able to construct the story while also tolerating all of these contradictions and complicating factors.

Do you see Hemingway as a tragic figure? And if so, why?

Novick: I do. It’s hard not to see him as a tragic figure. I can’t give you a textbook definition of tragedy, but in the discussion of the bullfight, Miriam Mandel gives us a definition of tragedy. She says tragedy is a high figure brought to a low place. Hemingway burns so bright. He’s so brilliant, he’s so successful, he’s so compelling, but the last 10 years of his life are just a devastating unraveling.

Burns: Well, first of all, he died by suicide. That is a personal tragedy. Because he was a celebrity, he was getting the wrong kind of help. And the stigma was so great, that no one talked about it, including him and his wife. There was no way to intervene to get him help. What killed him? Was it inherited family mental illness? Maybe. Was it PTSD from nearly being killed as a teenager in the trenches of Italy? Yeah, that could be it too. Was it the nine serious concussions? Was it alcoholism? Was it dementia? I can weigh all of those things, but I don’t really know. The image I have in my mind when you ask me if he’s a tragic figure is, he’s riding bareback on a horse in a thunderstorm, furiously trying to escape the horsemen of the apocalypse that are right behind him. And in the end, it doesn’t really matter which particular thing got him. All that matters is, he got gotten. That is a Shakespearean tragedy.

There was so much in the descriptions of his behavior—in his joy, in his high moments, in his creativity, and also in his anger and his low spells—that seemed like a textbook description of a mood disorder. You say, “He spent 50 years desperately trying to ride ahead of the apocalypse right behind him,” but you could just as easily flip it and say, “For 50 amazing years, he outrode the demons, lived in Cuba and Europe, won a Nobel Prize, and made love to hundreds of beautiful women.”

Burns: Yes! You’re absolutely right. Even as the madness is coming in, there’s glimpses and cracks of daylight, which we show. But I do think it’s a tragedy because of the way in which it falls apart. For a man with extraordinary discipline to no longer be able to edit himself is the most humiliating thing.

What do you hope people take away from the series? What nonliterary lessons can a viewer learn from Hemingway’s life?

Novick: That’s a very deep question. There’s the cautionary tale and the instructive examples. In a way, holding both in our minds is a good idea. On the plus side, he had a tremendous capacity to enjoy beauty, to be in the moment, to be present, to see the world around him with clarity, to see through bullshit and hypocrisy and to cut to the heart of things. That’s a gift and that’s something we could all try and emulate. He also had incredible discipline. Given all the challenges he faced as a human being, he did try and do his work every day. He didn’t have a boss telling him to work every day. He forced it on himself. There’s something really heroic about sitting down and doing the hard work every day, knowing that ultimately, it will be rewarding

On the other side of the ledger, he was so hungry for fame and desperate for recognition that it became a prison. The self-image he cultivated, the persona, the celebrity, and being surrounded by people who want to be close to you because you are famous. That’s a very hollow and empty existence. He paid a price for that.

Burns: Don’t become an alcoholic. Don’t not get help if you have suicidal ideation. That’s all I can say. The other thing is read; read Hemingway and everyone else. Since I started this project, I keep his collected short stories at the foot of my bed where I have my books piled up. Every once in a while, I pick one up. Ten minutes, 15 minutes … it is like a Zen poem. It is like a gift. I think to myself, “Oh my God, how could somebody rearrange these words in such a fashion as to rearrange my molecules?” And then I just say, “Bless you, Ernest Hemingway. I’m sorry it was such a difficult passage.”